Researching Italian-American surnames can be an exciting journey that bridges continents and centuries. Whether you are a beginner piecing together your family tree or an experienced genealogist tackling brick walls, understanding how to trace Italian heritage is key. Italian immigration to the United States peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – an estimated 5.5 million people left Southern Italy alone during that era (Italy wants to help you discover your roots—and meet distant relatives). They brought with them rich traditions and unique surnames that often hint at their origins. This article will help you research Italian-American surnames, from gathering U.S. records to delving into archives in Italy over various time periods.

Origins and meanings of Italian surnamesOrigins and meanings of Italian surnames

Italian surnames are packed with meaning and history. Understanding the origin of a surname can provide clues to your ancestral region or even an ancestor’s occupation or nickname. Italy boasts more than 350,000 distinct last names[1] – more than any other country – due to its long history of regional dialects and late national standardization. Most Italian surnames fall into a few broad categories of origin:

- Patronymic Surnames (From Given Names): Many Italian last names derive from a male ancestor’s first name. For example, D’Angelo means “son of Angelo.”. Often the ending of a name was changed – an -o ending turned to -i – to indicate “family of,” as in Alberti (from Alberto) or Giuliani (from Giuliano). Prefixes like Di, De, or D’ (meaning “of [someone]”) are common in patronymics (e.g. Di Giovanni, De Luca). A variant like De Angelis (literally “of the angels”) is essentially the plural or family form of D’Angelo.

- Occupational Surnames: Like English surnames Smith or Miller, Italian surnames often indicate a trade or profession. Ferrari (along with variants Ferraro, Ferri, Fabbri, etc.) comes from ferraro – the Italian word for blacksmith. Similarly, Molinaro and Molinari both mean miller, Sartori means tailor (from sarto), Contadino means farmer, and Barbieri means barber. Even noble or religious titles appear as surnames (though often indicating a family who worked for a noble household rather than actual nobility): e.g. Conte (count), Re (king), Abate (abbot). Some occupational names are a bit indirect – Zappa (hoe) suggests a farming family, and Vaccaro (cowherd) a cattle keeper.

- Descriptive or Nickname-Based Surnames: Italians commonly turned nicknames, based on personal appearance or character, into family names. For example, Rossi (and its southern variant Russo) means “red,” likely referring to hair color. In fact, Rossi is the single most common surname in Italy, especially in the north, while Russo dominates in the south – both harkening back to an ancestor with red hair. Other color-based names include Bianchi (“white” or fair-complexioned) as well as Bruno and Bruni (“brown-haired”). Physical traits gave rise to surnames like Ricci or Rizzo (curly-haired), Peloso (hairy), Spano (from spano, “short-haired” or possibly “bald”). Size and stature appear in names such as Longo/Longa/Luongo (tall or long), Grasso/Grassi (fat), Piccoli (small). Even traits like left-handedness (CsehMancini) or a notable feature (Quattrocchi – “four eyes”, for someone with glasses; Sanna – “prominent teeth”) became surnames. Don’t be surprised to find surnames meaning “fox” (Volpe), “wolf” (Lupo), “lion” (Leone or Leonardi), “cat” (Gatti), or even “turkey” (Tacchino) – Italians were creative in nickname origins! These colorful names can be a fun clue about your distant ancestor’s looks or personality.

- Geographical Surnames: Many Italian surnames derive from places – either the family’s town of origin or a geographic feature near where they lived. If your surname is also the name of an Italian city or region, there’s a good chance your ancestors adopted it after moving from that place. Common examples are Napolitano or Di Napoli (“from Napoli/Naples”), Romano (“from Rome”), Genovese (“from Genova/Genoa”), Toscano (“from Tuscany”), and Siciliano (“Sicilian”). Often these names were given when a person left one area and settled in another – e.g. a Calabrian in Naples might be called Calabrese. Every little town in Italy has spawned surnames; for instance, Fiorentino indicates origin in Florence, and Pugliese means someone from Puglia. Other geographic surnames describe landscape features: Montagna or Monti (living by a mountain), Costa (by the coast), Fontana (near a fountain or spring), Campo (field), Collina (hill), Della Valle (“of the valley”). Because Italy has been a crossroads, some surnames denote foreign origin: Tedesco (German), Greco (Greek), Spagnolo (Spaniard), Albanese, Turco, etc., often reflecting medieval migrations. Even Straniero literally means “foreigner”. If you encounter a surname like this, it might hint that the family came from elsewhere originally.

- Foundlings and Other Unique Origins: A subset of Italian surnames were historically given to orphans or foundling children. The most famous is Esposito, which literally means “exposed” or “placed outside” – a name given to babies abandoned to foundling wheels or orphanages in past centuries. Esposito is extremely common in Naples and Campania (it ranks among the top 5 surnames in Italy). Variations like Esposto, Degli Esposti (“of the exposed”), and Sposito are found in different regions. Other surnames with similar origin stories include Trovatelli (from trovato, “found”) and Colombo (often given to foundlings after Columbus as a benevolent namesake). Additionally, some surnames mean literally “abandoned” – e.g. Abbandonato – reflecting a tragic start to an ancestral line. While these names carry sad origins, they are an important part of Italian surname history.

Keep in mind that dialects and regional practices created variant spellings of what started as the same name. For instance, Rossi vs. Russo (north vs. south for “red”), or De Angelis vs. D’Angelo (one essentially a plural form of the other). In Sicily and parts of the south, surnames may include articles like Lo or La (meaning “the”), such as Lo Russo or La Monica, which are simply regional flavors of surnames (Lo Russo being equivalent to Il Russo, “the red-haired one”). Northern Italian surnames often end in -i, whereas southern names more commonly end in -o or -a. You might even notice regional suffixes: -etti, -ello, -illo can be diminutives (meaning “little” so-and-so), whereas -one can be augmentative (“big” so-and-so). All these clues can point to a surname’s localization. In fact, surname distribution maps show clear patterns – e.g. Rossi is widespread in Lombardia and Emilia-Romagna, while Russo dominates Campania and Sicily. Knowing this, if you only have a surname to go on, using a surname mapping website to see its Italian distribution can help narrow down which part of Italy your ancestors likely came from.

Regional distribution of common Italian surnames. Notice the North/South divide: Rossi (in green/red) is prevalent in northern and central regions, while Russo (purple) is common in the south . Surnames ending in -i (e.g. Bianchi, Gori, Innocenti) appear frequently in the North, whereas the South shows more -o endings and unique local names. Such maps illustrate how surname variants and popularity can be very regional, reflecting Italy’s diverse local histories.

Understanding the etymology of your Italian surname isn’t just academic – it can directly inform your research. If you learn your last name likely came from a certain region or town (for example, Pugliese from Puglia, or Palermo from the city of Palermo), you can focus your search there. Likewise, if family lore says your name was shortened or altered, recognizing the original form (say, knowing that DeStefano could also appear as Di Stefano or Stefano) will help you spot your ancestors in records despite spelling variations.

Getting started in the U.S.: Gathering clues from American recordsGetting started in the U.S.: Gathering clues from American records

For Italian-American genealogy, research usually begins on U.S. soil. Before jumping into Italian archives, collect all the information you can from your American records and relatives. Start by talking to your family: older relatives may recall the original surname spelling, the town of origin, or names of great-grandparents who immigrated. Don’t underestimate oral history – a simple detail like “Grandpa came from Naples” or “Our name was spelled with an -i in Italy” can guide your next steps. As one Italian genealogy blogger quipped, many of us regret not asking our grandparents more questions when we had the chance. So, gather those names, dates, and stories from living memory first.

Next, dive into U.S. records to find concrete evidence of your immigrant ancestors and their origins. Key American sources for Italian ancestry include:

- Federal and State Census Records: Census records (especially 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930) are a foundational resource. They can establish your ancestor’s approximate immigration year and whether they were naturalized. For example, the 1910 and 1920 U.S. Census have columns for “Year of Immigration” and “Nat’l Status” (NA for naturalized, AL for alien, PA for first papers filed). Seeing “Immigrated 1902, NA” in a 1920 census line tells you to look for a passenger list around 1902 and a naturalization record before 1920. Census records also provide names of other family members, ages (useful for estimating birth years), and sometimes even an exact birthplace. Early 20th-century censuses often list an immigrant’s birthplace as a country (e.g. “Italy”), but occasionally you might get a region or town (for example, some 1920 census entries list specific places like “Calabria” or “Sicily” under birthplace, though this was not consistently recorded). At the very least, knowing the region can help focus your Italian research. City directories can supplement census info, showing households year by year and sometimes indicating ethnic communities (for instance, areas in the directory dense with Italian surnames).

- Vital Records (Birth, Marriage, Death Certificates): These records created in the U.S. can yield important clues. A death certificate for your Italian-born ancestor might list their place of birth (sometimes just “Italy,” but it could name a town) and parents’ names (often the hardest part is the parents’ names, since the informant might not know or might Americanize them). A marriage certificate could list parents or at least confirm the person’s father’s surname and perhaps mother’s maiden name. In states like New York, early 20th-century marriage records for Italian-Americans often required a baptismal certificate from the old country, so the marriage register might note the Italian parish of baptism. A child’s birth certificate in the U.S. will list parents’ birthplaces – if the child was second-generation, it might say “Father born: Italy (town unknown)” etc., which at least confirms immigration.

- Passenger Arrival Lists: Immigration manifests are crucial for pinpointing an ancestor’s Italian hometown. Most Italian-Americans arrived through ports like New York (Ellis Island), Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans, or San Francisco, depending on the era and route. From 1892 to 1924, Ellis Island was the major entry point. You can search Ellis Island’s database (free) or use the Steven Morse One-Step search tool for more flexibility in spelling. Earlier arrivals (1855–1890) went through Castle Garden in New York (also with an online database), and pre-1855 arrivals are documented in customs passenger lists. The good news is that U.S. immigration officials did NOT arbitrarily change immigrants’ names at the port – a persistent myth we can lay to rest. Passenger lists were created by the shipping lines before the ship left Europe, and officials at Ellis Island merely checked off names from those lists. In other words, if a name was recorded incorrectly or “Americanized,” it likely happened either at the point of departure or later in the U.S., not by Ellis Island clerks. (The famous tale of immigrants getting their names butchered at Ellis Island is mostly Hollywood fiction.) Knowing this helps your research: if you’re struggling to find an ancestor in the manifests, consider that their surname on the list should still resemble the Italian version (perhaps with a slight spelling error), rather than a completely translated name. Look for creative spellings and use wildcards — for instance, Cappelli might be indexed as “Capelli” or D’Amico might appear as “Damico” with no apostrophe. Manifests after 1906 are especially informative: they list the last residence or birthplace in Italy and even the name and address of a relative back home (plus the relative or friend the passenger was going to join in the U.S.). If you find “Last residence: Cosenza” and “Mother: Maria Bianchi, Via Roma 10, Cosenza” on a manifest, you’ve just identified the hometown and a family member still in Italy at that time – golden information for the next stage of research!

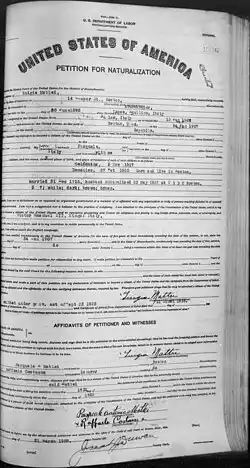

- Naturalization Records: For immigrants who became U.S. citizens, naturalization papers are invaluable. U.S. naturalization processes changed over time, but after 1906 they became standardized nationwide and the records are rich in detail. A Declaration of Intention or Petition for Naturalization typically provides an exact birth date and birth place (town and country) for the immigrant, and often the date and port of arrival. For example, a petition might read: “Giovanni Rossi, born 10 March 1885 in Palermo, Italy, arrived at New York on 5 May 1903 on the SS Sicilian Prince.” With that, you not only get the town (Palermo) but also the info needed to locate the ship manifest. If your ancestor’s naturalization took place before 1906, the information might be sparser (early records sometimes omit town of origin, unfortunately), but it’s still worth obtaining. You can find naturalization records in federal archives or sometimes county courts, and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services USCIS genealogy program can retrieve certain files (like alien registration forms or naturalization certificates) for a fee. Don’t forget to search for Naturalization indexes – many are online. And if an ancestor never naturalized, the 1940 Alien Registration (a requirement in 1940 for all resident aliens) might have a form with their birthplace and other data.

- Military Draft and Service Records: Many Italian immigrants or their sons served in the World Wars. World War I Draft Registration Cards (1917-1918), for example, include a field for place of birth – it often gives just country if abroad, but some registrants wrote the town (especially if they were recent immigrants proud of their hometown). World War II Draft Registrations (especially the Fourth Registration, or “Old Man’s Draft” in 1942 for men 45–64) often list the town and country of birth. These can provide or confirm the Italian town of origin. If your ancestor served in WWI or WWII, their service records or discharge papers might also state a birthplace. Even if they didn’t serve, nearly all men of appropriate ages filled out draft cards in WWI and WWII, making these a wide net to cast for information.

- Church and Community Sources: Italian immigrants in the U.S. often established or joined Catholic parishes that catered to the Italian community. Parish baptism, marriage, or death registers in America might record details not found on civil records. For instance, a marriage record in an Italian-American church might note the baptismal parish of the bride and groom in Italy (since proof of baptism was required). Ethnic newspapers (like Il Progresso Italo-Americano or local Italian papers) and fraternal organizations (e.g. Order of Sons of Italy lodges, or regional mutual aid societies named after their town of origin) can also contain tidbits: marriage announcements, obituaries, or club membership lists that mention specific hometowns. If your ancestors settled in cities like New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, or San Francisco, check if there were Italian-language newspapers – obituaries there often proudly state “native of [Town], Italy.” Some archives and libraries have these papers on microfilm or digitized.

- Gravestones and Cemetery Records: Visit or find photos of your Italian ancestors’ tombstones. Sometimes, Italian-born folks have their birth town or province inscribed on their grave marker (e.g. “Nato a Caserta, Italia” meaning “Born in Caserta, Italy”). Even if not, the birth and death dates on a stone can help you locate birth records once you have the town. Cemetery offices might have burial registers indicating who purchased the grave – possibly a clue if a burial was paid for by an Italian mutual aid society from a particular region.

In gathering U.S. records, be prepared for name variations. Many Italian names were modified in America, either by the individuals themselves or by record-takers unfamiliar with Italian spelling. A first name like Giovanni might appear as John, Giuseppe as Joseph, Pasquale as Charles/Patrick (believe it or not), Maria as Mary, etc. Surnames, too, might be spelled differently across records: Esposito could be Espostio in one census and Sposito in another, due to a dropped “E”. Don’t let these changes throw you off – recognize them as the same family. Compile all the clues from U.S. sources, and you should start to see a consistent picture of who your immigrant ancestors were, when they came, and ideally where in Italy they originated. That last piece – the Italian hometown – is the key to unlocking records overseas, so collect every hint that could point to it.

Handling surname variations and name changesHandling surname variations and name changes

One of the biggest challenges in Italian-American genealogy is navigating the spelling variations and changes of surnames over time. It’s common to find the same family recorded under slightly different names in different documents. Here’s how to tackle this hurdle:

Understand the Myth vs. Reality of Ellis Island Name Changes: As mentioned, Ellis Island officials did not arbitrarily change immigrant names upon arrival. The ship manifests were the primary source of names, and those were in Italian or other European spellings. However, name changes did happen in America – just not at the moment of entry. Many Italian immigrants themselves altered or shortened their names after living in the U.S. for a while, to better assimilate or because it made their lives easier. Some dropped di/de prefixes (e.g. Di Giacomo might become Giacomo or DiGiacomo might merge into Digiacomo), some translated their surnames (Cavaliere might become Knight, Montagna might become Mountain, though such literal translations were less common), and others just opted for a simpler spelling. For example, Lombardo might be shortened to Lombard, or D’Andrea might lose the apostrophe and become Dandrea. In other cases, given and middle names were shuffled – an immigrant named Vincenzo Giovanni might appear in U.S. records as John Vincent Smith (if Smith was an adopted surname). It’s important to keep an open mind and search for permutations of your family’s names.

Common Reasons for Name Changes: Immigrants faced various pressures and situations that led to modified names. Illiteracy played a role – if an immigrant could not spell their name for an official, the official wrote it as it sounded, which could introduce spelling errors. Some immigrants chose to adapt their surname to blend in, especially if they encountered discrimination or just wanted a fresh start. Others found Americans simply couldn’t pronounce Gnacci or Iacobucci correctly, so they adjusted it (perhaps Knatch or Yacob as extreme examples). There were also cases of clerical error over time – on censuses, draft cards, Social Security applications, etc., English-speaking clerks might accidentally Anglicize or misspell an Italian name. For instance, the surname Bianchi could be misheard as Blanke by an English ear, or De Carlo might be indexed under C because the clerk thought “DeCarlo” was the full last name. Understanding these possibilities will make you more effective in searching indexes and databases. Use wildcard searches (e.g. search for “Bian” to catch Bianco, Bianchi, Bianca) and try Soundex or phonetic matching when available.

Anglicization Examples: Some Italian surnames had well-known Anglicized forms: Di Giorgio sometimes became George, De Michele might become Mitchell, Ferraro could turn into Ferrer, and Marino sometimes became Marine. A famous example is the family of Giuseppe Garibaldi (the Italian hero) – some of his descendants in the U.S. went by Garibaldi while others shortened it to Garibal or changed it entirely. Surname changes were highly individual, though, so there’s no single rule. You might find one branch of a family kept the original spelling (Esposito), while another branch sliced off the ending to become Espo or took an English surname altogether after a marriage.

Spelling Variations in Italian Records: It’s worth noting that even in Italy, spelling could vary due to dialect or clerical interpretation until the 20th century when spelling became standardized. For example, a surname like Iannuzzi might appear as Jannuzzi (since “j” used to substitute for “i” in some records), or Chiara vs Ciara. When you start searching Italian records, be flexible with vowels and double consonants – Italians often use double consonants (e.g. Cappelli vs Capelli mean different things in Italian), but sometimes a clerk might miss one. Also, women in Italian records always appear under their maiden surname, even on their children’s birth records or their own death record. This is a crucial difference from American practice. So when searching for Grandma Rose’s birth in Italy, make sure you’re using her maiden name (which you might only have from her U.S. marriage or death record if at all). If you don’t know an ancestral woman’s maiden name, her American records (like marriage or the Social Security application of one of her children) may reveal it.

Tips for Resolving Name Issues: As you gather evidence, try to correlate data points to ensure you have the right person despite name differences. If the birth date matches and the spouse’s name matches across two records, you can be confident John Costa in one record is the same as Giovanni Costa in another, even if one says born in “Potenza” and the other “Italy.” Always cross-reference multiple sources. If a naturalization record uses a different surname than the ship manifest, see if the addresses or names of spouse/children line up – that can confirm the name change. It’s also helpful to make a list of all known variants of the surname and search each of them in databases. When in doubt, study the handwriting on old records – what looks like a different spelling might just be a fancy script “e” that you thought was an “o”.

Lastly, don’t forget that names could revert or alternate: some families used the Italian form in certain contexts and the American form in others. For example, an obituary might use the original Italian name (“born Giuseppe D’Amico”) even if the man went by Joseph Damico in life, or vice versa. By being aware of these patterns and persistent in checking all possibilities, you will overcome most name-related challenges.

Researching Italian records: Reaching across the oceanResearching Italian records: Reaching across the ocean

Once you have identified who your immigrant ancestor was and (ideally) their exact town of origin in Italy, you can begin researching records in Italy. This is where the journey gets truly exciting – you’ll be looking at documents your family members left behind in the “old country,” sometimes centuries ago. Italian genealogical research generally focuses on two major types of records: civil records (government vital records) and church records (parish registers).

Know Your Ancestral Town: In Italian research, everything is organized by town (comune). Unlike some countries, Italy has no nationwide index of births or central repository for all records. Each town or city maintained its own civil register, and each parish kept its own church books. Therefore, pinpointing the specific town (and province) is essential. If your U.S. research hasn’t yet yielded the hometown, take a step back and re-examine your sources or broaden your search – without the town, you’ll be casting a needle into a haystack. Clues to the town can be found in naturalization papers, passenger lists, Italian-American obituaries, draft cards, or even on gravestones, as discussed. If all else fails, consider using DNA matches or surname mapping (as mentioned earlier) to narrow down likely locations, and then seek records in those places for your family’s names. But assuming you have the town (or once you do), you’re ready to dive in.

Italian civil records (Stato Civile)Italian civil records (Stato Civile)

Italy’s civil registration (stato civile) records are a genealogist’s goldmine. They include births, marriages, and deaths, and sometimes other documents, and they often contain more detail than contemporary American vital records. The availability of civil records depends on time and place due to Italy’s history:

- Napoleonic Civil Registration (1806–1815): Civil record-keeping in Italy began in the Napoleonic era. When Napoleon conquered large parts of Italy, he introduced civil registration (separate from church authority) starting around 1806 in the north and 1809 in southern Italy. For example, many areas of present-day Italy have civil birth, marriage, and death records beginning in 1809. (Sicily started a bit later, in 1820, adopting these practices under the Bourbon monarchy.) These early records can be a bit sparse, but by around 1810 they typically include the key information – names of the child or couple and their parents.

- Restoration Period (1816–1865): After Napoleon’s fall in 1815, some regions (especially in the North) discontinued civil recordkeeping and reverted to church records until unification. Other regions (notably the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south) continued civil registration consistently through the mid-1800s. This means if your ancestors are from southern Italy (e.g. Campania, Calabria, Apulia, Sicily), you’ll likely find civil records right through the early 19th century. If they’re from places like Tuscany or Veneto, you may find a gap where only church records exist until 1866. It varies, so consult a timeline for your region. One quirk of this period is the use of marriage processetti or allegati – these were supplemental documents for marriages that could include copies of birth and death records of the bride, groom, and even their parents, sometimes reaching back into the 1700s. If available, processetti are treasure troves – imagine getting your 4th great-grandparent’s death record as part of an 1830 marriage file! Always check if marriage records mention appendices, and look for those in the archives.

- Post-Unification Civil Registration (1866 onward): After Italy’s unification (1861-1870), civil record keeping became standardized nationwide. From 1 January 1866, Italy mandated that all towns keep civil records in a uniform format (some areas like Rome province started a bit later in 1871 due to the Papal States until 1870 ). These late 19th-century and early 20th-century records are usually well-organized, often typed or on printed forms, and sometimes even have annual indices. They also introduced features like margin annotations – a person’s birth record might have notes added later about their marriage or death (even if it occurred decades later, or in another town). The Stato Civile records from the 1866–1910s period are very detailed and easier to read than earlier ones.

Now, what information can you expect in these civil records? A lot! Here’s a quick rundown:

- Birth records (Atti di Nascita): A birth act will include the child’s name, date and time of birth, and place of birth (often an address, or at least “in the house at Via , No.”). Crucially, it names the father and mother, including the mother’s maiden name, their ages, occupations, and residence. It will also name whoever reported the birth (often the father, or a midwife) and may list two witnesses. In some cases, it notes if the child was baptized and where (earlier records might include baptismal info). Women’s maiden surnames are always used – so it might say “Maria Bianchi, wife of Luigi Rossi” but will still call her Bianchi if that’s her maiden name. Later birth records (after 1900) might have a margin note if the person married or died, which can lead you to those records.

Example of a late 19th-century Italian birth register. This pre-printed Atto di Nascita form from 1881 (Comune of Buccino) shows the standardized format introduced after 1875. Italian civil birth records typically provide the child’s name and gender, exact birth date and time, place of birth, and the parents’ details (names, ages, occupation, residence). Two witnesses (“testimoni”) are listed, and the declarant (often the father) signs at the bottom. Such records are rich in genealogical data, often including the mother’s maiden name and the family’s address.

- Marriage records (Atti di Matrimonio): A civil marriage act gives the date of the marriage and all the vital details of bride and groom: names, ages, birthplaces, occupations, and residences, plus parents’ names (including mothers’ maiden surnames, and whether each parent is living or deceased). It will also list the names, ages, occupations, and residences of witnesses. Earlier marriage documents (pre-1865) might include church marriage info if a church ceremony was involved; after Unification, civil and church ceremonies were separate (couples married civilly at town hall and could also have a church wedding). If you’re lucky, marriage records may contain marginal notes about eventual divorces or annulments (rare in older times) or, as mentioned, you might find a bundle of marriage allegati/processetti with birth extracts of the bride and groom and death extracts of their parents or grandparents. Always seek out the allegati for 19th-century marriages as they can extend your tree further back.

- Death records (Atti di Morte): A death act will typically provide the date and place of death, the deceased’s name, age, occupation, and residence, and often their birth town if different. It also usually names the deceased’s parents and spouse (if married). One important thing: Italian death records list women by maiden name (“Maria Bianchi, wife of Rossi, died…”), which is very helpful for identifying women. Sometimes a death record is how you learn an ancestor’s mother’s maiden name, if you haven’t seen the birth. Death acts may be less detailed about parents if the informants didn’t know all the info, but they’re still very useful for confirming a person’s existence and approximate birth year.

In addition to these, you might come across Cittadinanze (citizenship records), Pubblicazioni (marriage banns), and Liste di Leva (military draft lists) in Italian archives, which can further flesh out the picture. Draft lists, for example, recorded all males of a certain year when they reached draft age (usually around 18-20), and they often confirm birth date and parents’ names. If your ancestor didn’t emigrate until after draft age, you might find him listed in the Italian draft registers with notes like “emigrated to America in [year]” – a neat cross-link.

Accessing Italian civil recordsAccessing Italian civil records

Fortunately, accessing Italian civil records has become much easier in recent years thanks to digitization projects. There are several avenues to find your ancestors’ records from home:

- Antenati (Portale Antenati): The Italian State Archives’ Ancestors Portal is a free online repository of civil registration images. It has been expanding rapidly. As of the mid-2020s, Antenati hosts millions of images of birth, marriage, and death records from about 1809 through the 1940s (coverage varies by area). The portal was launched in 2011 and by 2018 had over 71 million images from 52 state archives – and it keeps growing. You can search or browse by province and commune. For example, if your family is from Comune di Avezzano in L’Aquila province, you would find L’Aquila in Antenati, then browse Avezzano’s records for the relevant period (Napoleonic, Restoration, or Italian Civil State). The website is available in English and Italian, and it’s free – you just might need to be patient with navigation. Some archives have even indexed records by name, but many require page-by-page browsing of registers (don’t worry – usually there are handwritten indices at the end of each year). Antenati is an incredible resource that saves you from having to travel or request records by mail if your area of interest is covered.

- MyHeritage: The MyHeritage website has over 25 Italian-related searchable online databases including Italy, Births and Baptisms, 1806-1900, Italy, Marriages, 1809-1900, and Italy Deaths and Burials, 1809-1900.

- Local Civil Record Offices (Comune Ufficio di Stato Civile): If the records you need are not online (for instance, post-1910s records often aren’t, because of privacy restrictions or simply not digitized yet), you may need to request documents directly from the town. Italian law generally protects birth records less than 100 years old and marriage/death records less than 70-75 years old. However, direct descendants can request certificati (certificates) for research or legal purposes. You can write to the Comune’s registry office and request, say, a birth certificate of your grandfather born in 1930. Write in polite Italian, include as many details as possible (full name, birth date, parents’ names if known), and include your relationship and reason (family history). Many comunes will reply for free or a small fee, though response times vary. Some might email you a digital certificate. Remember to use the Italian forms of names when writing (e.g., write “Giovanni” not “John” when referring to his Italian birth). If language is a barrier, templates for Italian record request letters are available.

- State Archives: Each Italian province has an Archivio di Stato, which often holds duplicate sets of civil records (especially the older ones) and military drafts, etc. If something isn’t on Antenati yet, you could contact the Archivio di Stato for that province. Some of them have their own websites and even digitized collections separate from Antenati. For example, the Archivio di Stato di Napoli might have a separate portal for certain years. Check the state archive website or the Antenati portal updates if you can’t find your town’s records online; it might be that they’re pending digitization or available via a different site.

- Professional Researchers: If traveling to Italy or navigating Italian bureaucracy is daunting, you can consider hiring a professional genealogist in Italy. Many specialize in regional research and can pull records from both civil and church archives on your behalf. Before you hire, though, exhaust the online avenues – you’d be surprised how much you can gather from home with patience.

Italian church records (parish registers)Italian church records (parish registers)

Civil records in Italy generally cover back to the early 19th century (or mid-16th in a few places during Napoleonic rule). But what if you want to go earlier? That’s when you turn to church records – the parish registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials maintained by the Catholic Church.

Thanks to the Council of Trent’s decree in 1563, Catholic parishes were required to keep registers of baptisms, marriages, and deaths. In practice, many parishes in Italy have records starting in the late 1500s or early 1600s. This means you could potentially trace your family several generations further back before civil records begin. For example, if your ancestor was born in 1780 in a small village, you will need to find their baptism record in the parish books.

Accessing Parish Records: Church records are not as centralized or as easily accessible online as civil records, but the situation is improving. Some Italian dioceses have diocesan archives where old parish books are stored and can be accessed by appointment or request. Other registers remain in the local parish church. To get these records, you often have to write to the parish priest or the curia (diocesan office) for that area. Write in Italian, be respectful (these are clergy who are often very busy), and specifically request the entry you need (e.g. “the baptism of so-and-so on or around X date”). Providing a small donation or offering to cover expenses is considerate. Sometimes local volunteers or genealogical groups have indexed parish records – it’s worth searching online for “[Town Name] battesimi matrimoni registri” to see if someone has transcribed them. For instance, some parishes in Sicily and other regions have been indexed by volunteers.

What’s in Parish Registers: A baptism (battesimo) record typically gives the infant’s name, baptism date (often very soon after birth), parents’ names (sometimes including the mother’s maiden name, sometimes not), and godparents’ names. Early baptisms might not explicitly state the birth date, but usually they baptize within a few days of birth, so it’s close. Marriage (matrimonio) records list the couple and their parents (and often the couple’s ages or at least note if a parent is deceased). They may also mention if a dispensation was needed (for example, if the couple were related). Burial (morte) records usually name the deceased, give a burial date (often date of death as well), age or approximate age, sometimes spouse’s name (“wife of ___” or “widow of ___”), and occasionally parents’ names (earlier ones might not mention parents for an adult, but later ones often do).

Be aware of challenges with church records: they are handwritten in Latin (or sometimes in Italian or local dialect). Latin versions of names will be used (e.g. Joannes for Giovanni, Gulielmus for Guglielmo, Maria stays Maria). The handwriting can be hard to read, and records can be missing due to events like fires, floods, or wartime destruction. In some areas, Napoleonic and later civil records partially duplicated what the church had, so sometimes the church stopped recording burials if civil records took over – but many priests kept parallel records.

Despite difficulties, these records are often the only way to trace back into the 1700s and 1600s. It’s a thrilling feeling to find, say, the 1742 marriage of your 5th-great-grandparents in a church ledger, signature and all. Keep in mind naming patterns: Italian families often named children after grandparents in a set order (first son after the paternal grandfather, second son after maternal grandfather, first daughter after paternal grandmother, second daughter after maternal grandmother). If you see the children’s names in baptisms following this custom, it can confirm you have the right family or even help predict an unknown grandparent’s name.

Finally, note that parish registers may have gaps or have been consolidated. In some towns with multiple parishes, older registers might have been moved to a central “mother church” or archive. Always ask the local authorities if you’re not finding something – they might point you to a neighboring village if, say, one parish served several small hamlets.

Making modern connections and advanced tipsMaking modern connections and advanced tips

Researching Italian-American surnames isn’t just about dusty old records – it’s also about connecting with living relatives and community knowledge that can enrich your family history. Here are some advanced tips and modern strategies to consider:

- Connect with Living Relatives in Italy: You may have cousins in Italy that you’ve never met. Once you know your ancestral town and have built a family tree a few generations back, you can try to identify branches that stayed in Italy. Modern technology makes this easier than ever. One method is to use the Italian online white pages (Pagine Bianche) to search for people with your surname in the ancestral town or province. A polite letter or Facebook message (in Italian, if possible) explaining your connection and interest in family history can sometimes open a dialogue. In many cases, Italians are just as curious about their American cousins! Social media is a powerful tool – there are Facebook groups for genealogy (even specific to regions, like “Genealogia Italiana” groups) and groups for people from certain towns (for example, “Sei di [Town Name] se...” pages where locals and expatriates chat). Posting in such a group that you’re researching your family from that town might lead to helpful responses. An example: a researcher posted in a Sicilian town’s Facebook group looking for any Tringali family, and found an elderly man who remembered the family that emigrated in 1910 – it turned out to be her great-grandfather’s nephew, who connected her with the rest of the relatives still there.

- Leverage DNA Testing: DNA has revolutionized genealogy in recent years, and Italian-American research is no exception. Taking an autosomal DNA test (through companies like MyHeritage) can match you with genetic cousins. You might find distant cousins in the U.S. who descend from siblings of your immigrant ancestor – collaborating with them can fill gaps. Even more exciting, you might get matches in Italy or Argentina, Brazil, Australia (since Italians emigrated worldwide). Contacting a DNA match who has a familiar surname or tree listing your ancestral town could lead to breakthroughs. Additionally, consider a Y-DNA test if you want to trace the direct paternal line of a surname – males with the same Italian surname who match on Y-DNA can confirm a relationship and sometimes pinpoint a common region. As DNA databases grow, the chances of connecting with relatives in the old country increase; in fact, the surge in “roots tourism” – people traveling to meet family found via genealogy and DNA – has been so notable that Italy declared 2024 the “Year of the Italian Roots in the World” to encourage these reconnections (Italy wants to help you discover your roots—and meet distant relatives). Using DNA evidence alongside paper records can also help verify that the Luigi Rossi you found in records is truly your Luigi Rossi (if a known second cousin’s DNA matches you both, it’s a good sign you have the right line).

- Italian Genealogical Societies and Resources: Tapping into community knowledge can save you time. In the U.S., there are organizations like the Italian Genealogical Group (IGG), which has indexed tons of records (especially in New York; they have free databases for NYC vital records indexes, naturalizations, etc., which are extremely useful if your Italians settled there). The National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) and local Italian-American societies sometimes host genealogy workshops or have resources for members. Online, forums and subreddits (e.g. r/Genealogy with flair for Italy questions) let you ask specific questions – often someone with experience in that area will guide you. Taking some time to read these guides can make you more self-sufficient as a researcher.

- Language and Document Help: You do not need to be fluent in Italian to do this research (though learning a bit is rewarding!). Genealogical documents use a relatively formulaic language. There are many aids available: word lists of common Italian (and Latin) genealogical terms, translation guides, even scripts of typical civil records with blanks filled in. For example, knowing that “l’anno millenovecento venti” means 1920, or that “nato da” means “born to [parents]” will help you skim documents. Over time, you’ll recognize key words (figlio/figlia = son/daughter, fu = “was” indicating a parent is deceased, nato/a = born, moglie = wife, celibe/nubile = unmarried man/woman, etc.). Handwriting is another hurdle – you may need to familiarize yourself with old script. Again, online guides and practice will make it easier, or you can ask for a second pair of eyes on forums if a record’s scrawl has you stumped.

- Traveling to Italy for On-Site Research: If you have the opportunity, visiting your ancestral hometown in Italy can be incredibly rewarding. Before you go, do your homework: contact the Comune in advance if you plan to search records there (some require appointments to see old registers, and some might just hand you the certificates if you ask). Visit the local parish church – sometimes the parish priest or staff will show you the old books if you explain your quest, or at least let you know where the records are kept. Walking the local cemetery can yield family names and dates (many Italian cemeteries have graves dating back only to early 1900s due to reuse, but you might find relevant surnames still present). Even if you don’t access new records, just seeing the street your ancestor lived on, or the church where they married, is a powerful experience. Italy’s Year of Roots initiative mentioned earlier is even encouraging small towns to help international visitors find their family heritage (Italy wants to help you discover your roots—and meet distant relatives) (Italy wants to help you discover your roots—and meet distant relatives). Who knows – you might be welcomed by a distant cousin with open arms, as often happens on shows like “Finding Your Roots” and in real life stories.

- Keep Organized and Document Your Sources: As a final advanced tip, treat your Italian surname research like any genealogical project – cite your sources and keep notes of where you found each piece of information. You will likely accumulate dozens of records in languages you’re translating; keeping them labeled (like “Birth of Giovanni Caruso, Terrasini, 1880, from Antenati image 123”) will help if you need to refer back or share with family. Also, note the naming conventions used in your tree: perhaps you want to list ancestors with their Italian names and in Italian order (first name then surname) for clarity, rather than translating everything. Consistency will help avoid confusion, especially when many relatives have similar names repeated every generation (all those Pietros, Giovannis, Marias, etc., which is very common due to the naming customs).

Recommended resources for Italian surname researchRecommended resources for Italian surname research

To empower your research further, here is a curated list of recommended resources – websites, databases, and books – that are invaluable for Italian-American genealogy:

- Portale Antenati (Italian Archives): Official Italian government site with millions of free scanned civil records. Browse by province and commune. An essential first stop for Italian records online.

- MyHeritage: The MyHeritage website has over 25 Italian-related searchable online databases including Italy, Births and Baptisms, 1806-1900, Italy, Marriages, 1809-1900, and Italy Deaths and Burials, 1809-1900.

- Ellis Island & Castle Garden Passenger Lists: The Ellis Island Foundation website for arrivals 1892-1924 (with free search; registration required to see manifests). Castle Garden for New York arrivals 1820-1891. MyHeritage also have these manifests indexed with images.

- Italian Genealogical Group (IGG) Databases: Free indexes for many New York area records (especially naturalizations, marriages, etc.) which are extremely helpful if your ancestors passed through NYC.

- Family Tree Books on Italian Genealogy: Finding Italian Roots: The Complete Guide for Americans by John Philip Colletta is a classic, offering step-by-step guidance (updated edition available) – it’s both beginner-friendly and detailed for advanced researchers. Italian Genealogical Records by Trafford R. Cole focuses on how to use civil and church records in Italy and interpret them, with lots of examples – very useful when you start working with Italian-language documents. Also, Our Italian Surnames by Joseph G. Fucilla (1949, reprinted) is an interesting read on the origins and meanings of Italian last names, if you want to dive deeper into surname etymology and lore.

- Local and Regional Histories: If you’ve identified your ancestral town, look for a local history book or website. Many Italian towns have a published history that might mention families or contain transcribed records. For example, some towns have “La storia di [Town Name]” books that include lists of old residents or notable emigrants. Even if they’re in Italian, they could contain names and dates you can extract.

- Online Forums and Social Media: The subreddit r/ItalianGenealogy are great places to ask questions. Facebook groups like Italian Genealogy or region-specific groups (e.g. “Calabria Genealogy” or “Sicilian Genealogy”) have active members willing to help newcomers. Don’t hesitate to join and post your query – list the surname, town, and what you’re seeking; you may find someone who is researching the same area or even the same surname.

- Genealogical and Historical Archives in the U.S.: Remember to check U.S. sources beyond the obvious. For example, the National Archives (NARA) for ship manifests and naturalizations outside major sites, state archives for things like alien affidavits or old state census, and local historical societies in the cities your ancestors lived (they might have ethnic church records, Italian newspapers, or community documents not found elsewhere). The New York Public Library and other large libraries often have ethnic genealogy guides and sometimes collections like Italian parish record microfilms or Italian newspapers.

ConclusionConclusion

By leveraging these resources and the strategies outlined above, you will be well-equipped to trace your Italian-American surname through generations and across the ocean. Remember, genealogy is a journey of discovery. Each record you find is a puzzle piece that adds to the picture of your ancestry. Along the way, you’ll likely gain a deeper appreciation for your Italian heritage – the meanings behind your family name, the hardships and hopes of your immigrant forebears, and the living connections that still exist between Italy and America.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Italian American SurnamesExplore more about Italian American Surnames

- Last name research on MyHeritage

- Italian historical record collections on MyHeritage

- Italian Surnames: Uncovering the Rich Heritage of the Zeppetelli Family on the MyHeritage Blog

- Researching your Italian Heritage on the MyHeritage Facebook Page

- Exploring Italian Surnames - Italian Culture Oggi

- Italian Genealogical Group

- Italian Surnames Lists - Surnames in Italy

- Most Common Surnames in Italy By Region - Brilliant Maps

- National Italian American Foundation

- Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America

- Portale Atenati

- Steven Morse One-Step

References

- ↑ Italian Surnames. Mount Carmel - Saint Cristina Society