Ashkenazi Jewish surnames are hereditary family names that are commonly found among the Ashkenazi Jews, a diasporic Jewish community who started to take form in the Western Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE,[1] and later settled in Germany and Eastern Europe between the 13th and 17th centuries. Ashkenazi Jews have made very important contributions to Western science, culture, philosophy, and politics despite the community's small size and diasporic situation, influencing the entire Jewish world due to their relative majority, especially after migrating to North America, South America, Australia, and South Africa.

History of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames

The use of surnames among Ashkenazi Jews began relatively late compared to other European populations. While Sephardic Jews in the Iberian Peninsula adopted permanent family surnames as early as the 10th or 11th century and brought them with them after the Alhambra Decree, Ashkenazi Jews in Central and Eastern Europe did not widely adopt surnames until the 18th and 19th centuries, when surnames became mandatory in almost most of Europe, when government authorities who required citizens to take last names for taxation, conscription, and education purposes. The first place in the region where Jews were mandated to have a hereditary surname was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when Emperor Joseph II signed a law in 1787 that forced all Jews from the Empire to take a German fixed hereditary surname.[2][3] By 1835, Czarist Russia became the last country in Europe to make hereditary surnames mandatory. [4]

Ashkenazi Jewish naming conventions

Ashkenazi Jews traditionally named their children after deceased relatives as a way to honor their memory and inspire the namesake to live up to their predecessor's better qualities. As in most places of the Western World, Ashkenazi women tend to adopt their husband's name upon marriage, with some retaining their maiden name or combining it with their husband's surname in those countries where it is permitted.

Spelling variations of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames

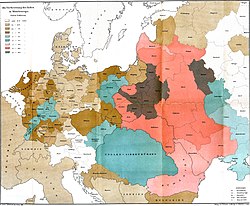

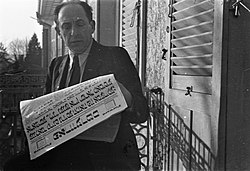

Due to the fact that Ashkenazi Jews have lived in areas that spread over most of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as some areas of Western Europe, their surnames may be spelled differently based on the spelling standards used by each country, which vary according to the country's official language in usage by the registrars. For example, the surname spelled in German Gutzeit is spelled Hutcajt in Polish, Huttsayt in transliterated Ukrainian and Hutțait in Romanian. TWith Central and Eastern European borders changing dramatically over the course of time, a person living in a city that was Austro-Hungarian, then Polish, and ultimately Soviet could have documents with their surname spelled in three different ways. Another, less common example could be the surname Shabashewitz, which is rendered in Lithuanian documents as Šabasevičius, Belarusian and Ukrainian-language documents would print it as Shabashevich and the surname would be rendered in Russian as Sabsovich. These variations can make researching for an Ashkenazi Jewish ancestor a challenge; however, when taking into account this fluidity, the research can be made easier.[5]

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of patronymic origin

A significant number of Jewish surnames are of patronymic origin, and are generally identified by the suffixes -s, -son, -sohn, -ovitch, -owitz, -vici, -ovics and rarely -zon, which were assigned at the moment of the adoption of the hereditary surname. The surname of the rebbes of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic dynasty, Schneersohn, derives from the name of the dynasty’s founder, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi.[6]

- Levinson, "son of Levi", which apart from being a surname can also be a given name

- Schneersohn, "son of Shneur"

- Isaacs, "son of Isaac"

- Jacobson, "son of Jacob"

- Aaronson, "son of Aaron"

- Shabashewitz, "son of Shabtai"

- Mordkovich, "son of Mordechai"

- Abramovich, "son of Abram"

- Leibowitz, "son of Leib"

- Mendelssohn, "son of Mendel"

- Gershenzon, "son of Gershon"

- Markovich, "son of Markus"

- Yankelovich, "son of Yankele", a pet form of Jacob in Yiddish

- Moskowitz, "son of Moshke", a pet form of Moses in Yiddish

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of matronymic origin

One interesting aspect of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames is the relatively large number of surnames based on the name of a mother or other female ancestor, often ending with the suffix -in, such as the surname Rivkin, which comes from the female name Rivkeh (the Yiddish form of Rebecca), the surname, Sorkin, derived from the female given name Sarah, the surname Feiglin, derived from the female given name Feiga and Belkin, derived from the female given name Beila,[6] and Gittelman, meaning "husband of Gittl".[7]

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of occupational origin

Throughout history, occupations for Ashkenazi Jews were very limited in Central and Eastern Europe, which limited the number of occupational surnames as well. Perhaps the most common one is Rabinowitz, a surname is derived from the Hebrew word "rav," meaning "rabbi" or "teacher," which indicates that the bearer is a descendant of a rabbi or comes from a family of religious scholars. Other Ashkenazi Jewish surnames associated with occupations are Sarver ("caterer"); Schechter (ritual slaughterer); Spivak and Kantor, (both meaning "cantor"); Zuckerman ("sugar seller"); Kramer ("storekeeper"); Kaufman ("merchant"), Metzger ("butcher"), Reiter ("horseman") and Diamant ("diamond", usually given to a jeweler).[8]

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of toponymic origin

A significant number of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames are derived from a town or region, most likely indicating the bearer's ancestors were from that area originally, with most surnames ending in the Germanic and Yiddish -er, but sometimes adopting the slavic forms cki or -ski,[6] or simply the name of the city or town itself. Common examples of these surnames are:

- Shapiro, from Speyer, Germany

- Horowitz from Hořovice in today's Czech Republic.

- Breslauer, from Breslau (today Wrocław) in Poland

- Danziger, from Danzig (today Gdańsk) in Poland)

- Posner, from Posner (today Poznań) in Poland)

- Krakauer, from Krakau (today Kraków) in Poland)

- Oppenheimer, from Oppenheim, Germany

- Minsky, from Minsk, Belarus

- Perski, from Pershai, Belarus

- Królicki, from Królik, Poland

- Sieradzki, from Sieradz, Poland

- Twerski, from Tverai, Lithuania

- Wilner, from Vilnius, Lithuania

- Wertheimer, from Wertheim, Germany

- Pollack, from Poland

- Wiener, from Vienna, Austria

- Halperin, from Heilbronn, Germany

- Unger, from Hungary

- Ullman, from Ulm, Germany

- Altshuler, from the Altshul in Prague, Czechia

- Hollander, from Holland, a region of the Netherlands, usually mistaken as the name of the country

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of descriptive origin

There is an abundance of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames that are based on a personality or physical trait of the bearer; many of these have a negative meaning and were assigned to Jews who may have not been able to afford adopting a less offensive one,[7] like Kleinkopf ("small head"), Altman (“old man”), Deligtisch (“criminal”), Sommerfeind (“enemy of summer”) and Lügner ("liar"). Other descriptive surnames are:

- Dreyfus ("three-legged")

- Weiss ("white")

- Roth ("redhead")

- Zilber ("silver")

- Gelfand ("elephant")

- Mandel ("almond")

- Stern ("star")

- Adler ("eagle")

- Birnbaum ("pear tree")

- Hirsch ("deer")

- Soloveitchik ("little nightingale")

- Rosenfeld ("rose field")

- Meersand ("sea sand").[3]

- Schwartz (also spelled Shvarts), derived from the German word "schwarz," meaning "black"

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Hebrew origin

Most of the Ashkenazi Jewish names of Hebrew origin are associated with religious activities or roles, such as:

- Cohen and its spelling variants Kohen, Kahn, Kohn and Kogan - this surname is derived from the Hebrew word for "priest" and indicates that the person is a descendant of the ancient Jewish priestly class. Most, but not all, bearers of these surnames have the role of Kohen, a specific status in Judaism.[6]

- Katz - the abbreviation in Hebrew (כּ״ץ) formed from the initials of the term Kohen Tzedek, meaning "priest of justice". Just like with the previous one, most bearers of these surnames have the role of Kohen, a specific status in Judaism.[6]

- Levin and its spelling variants Levine, Levy, Levit and Levitt - this surname is derived from the Hebrew name Levi, one of the twelve tribes of Israel and it is connected to the Levite tribe, which had religious and educational responsibilities in ancient Israel, and most but not all, have the religious status of Levi.[6]

- Segal, an abbreviation of sgan leviyyah, meaning "assistant to the Levites".[9]

- Rabinowitz (also Rabin, Rabinek, Rabinovitch) - this name is derived from the Hebrew word "rav," meaning "rabbi" or "teacher." It indicates that the bearer is a descendant of a rabbi or comes from a family of religious scholars.

- Sagan - an import from the Aramaic Segan (סְגַן), which appears 5 times in the Bible, in the Aramaic sections of the Book of Daniel to refer to officers of the Babylonian government and also appears in the Talmud to indicate a stand-in position.[10] The term was rendered in Hebrew as Sagan (סָגָן), which can be found 17 times in the rest of the Tanakh, especially the book of Nehemiah, referring to officials of the Babylonian rulers.

- Margolis, a surname shared by many famous rabbinic personalities, derives from the female name Margalit, which means “pearl” in Hebrew.

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Germanic origin

The Ashkenazi Jewish community developed originally in the valley of the Rhein (a region called "Ashkenaz" in medieval Hebrew) where they adopted High German and fused it with elements taken from Mishnaic Hebrew and Aramaic. The resulting dialect became their lingua franca, which they took with them as part of their identity in their expansion towards Central and Eastern Europe. This means that the influence of German is the most significant in the surnames they adopted. Most of them have the -er ending to denote location, -man (as opposite of "-mann" in German) to denote occupation, ü evolved into i, au becoming oy and the c in Sch is dropped, in most cases being written as sh.[11] This makes Ashkenazi surnames of German origin easily identifiable, like Hoffman ("steward"), Kessler ("kettle-maker"), Alchimister ("chemist"), Deutsch ("German"), and Friedman (from the German word friede, meaning "peace").

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Slavic origin

Even though Ashkenazi Jews have lived for more than a millennia in Central and Eastern Europe, the influence of Slavic surnames is relatively recent, and mostly restricted to the Former Soviet Union. This is because in the rest of Central and Eastern Europe the language of administration and prestige was German for most of the time Jewish communities lived there, followed by Hungarian and Romanian. Nevertheless, it is possible to find Ashkenazi Jewish names with a noticeable Slavic influence are mostly originated in the Pale of Settlement,[12] many ending with the suffixes -in, -ov, -ny and -ski for men and -ina, -ova, -naya and -skaya for women, like the following:

- Duchovny ("clergyman" in Polish)

- Kanievski ("from Kaniev", in Ukraine)

- Chernomordik ("black-faced" in Russian)

- Portnoy ("tailor" in Russian)

- Chubatovsky ("forlocked" in Russian)

- Sapozhnik ("shoemaker" in Russian)

- Mendelovich ("son of Mendel" in Russian)

- Solovey ("nightingale" in Russian)

- Raskin (matronymic form of the name "Raske" in Russian)

- Bialik ("pale" in Polish)

- Bakalarz ("schoolteacher" in Polish)

- Bloch (from włoch, "Italian" in Polish)

Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Hungarian origin

See also: Hungarian Jewish surnames

Most Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Hungarian origin diverge significantly from those from the rest of the Ashkenazi Jewish diaspora due to two the Magyarization of surnames for non-Hungarians, which took place between 1840 and 1849 and in 1867 with the establishment of the Dual Monarchy. This change caused many Hungarian Jews to change their family names from German to Hungarian, in a process that occurred both voluntarily and as a result of social pressure. Hungarian was the only language allowed to be used in civil administration, legal proceedings, and higher education in that part of the Dual Monarchy. As most Jews were urban in Hungary, a majority of the middle-class Jews changed their surnames to more Hungarian-sounding ones and started to use only Hungarian as a medium of communication in search of social mobility.[13] Among the most common Ashkenazi Jewish surnames of Hungarian origin are Farkas, Nagy, Kis, Jakab, Szabó, Harsányi and Erős.

Hebraization of Ashkenazi Jewish surnames

See also: Hebraization of Jewish surnames

Upon their aliyah (immigration to the Israel), many Ashkenazi Jews chose to change their surnames and adopt one in Hebrew, in many cases to reinforce their new identity as Jews living in the Land of Israel and their rejection of the Diaspora, and others also to get rid of surnames with negative connotations, like Ausuebel ("from evil") becoming Ben-Tov ("good son"), Zwerg ("dwarf") becoming Adir ("mighty") and Lügner ("liar") becoming Amitai ("honest").

Celebrities with Jewish surnames

- Barbra Streisand, American singer, actress and filmmaker

- Ezra Matthew Miller, American actor

- Luciano Lebelson Szafir, Brazilian actor

- Diego Sebastián Schwartzman, Argentinian Tennis player

- Milena Markovna "Mila" Kunis, Ukrainian-American actress

- Yaël Judith Braun-Pivet, current president of the French National Assembly

- Donna Ivy Karan (born Faske), American fashion designer

Explore more about Ashkenazi Jewish surnames

- Last names on MyHeritage

- Historical records from Israel on MyHeritage

- JewishGen.org

- Avotaynu

See also

References

- ↑ Mosk, Carl. Nationalism and economic development in modern Eurasia. New York: Routledge, 2013. ISBN: 978-0-415-60518-2.

- ↑ Zaleisky, Adalbert (1854). Handbuch der gesetze und verordnungen welche für die polizei-verwaltung im österreichischen kaiserstaate von 1740–1852 erschienen sind. F. Manz. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-1-148-91162-5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Did Jews Buy Their Last Names?. The Forward

- ↑ Paull, Jeffrey Mark; Briskman, Jeffrey. History, Adoption, and Regulation of Jewish Surnames in the Russian Empire. Surname DNA Journal

- ↑ Some Issues in Ashkenazic Name Searches. Avotaynu Online

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 10 Keys to Understanding Many Ashkenazi Surnames. Chabad Lubavitch

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jewish Surnames Explained. Slate

- ↑ Dictionary of American Family Names

- ↑ Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History ed. Kinga Frojimovics, Géza Komoróczy - 1999 p190 "Siegel / Segal / Segall / Chagall, etc.: segan levayya, leader of the Levites (sagan is a loanword from Ancient Mesopotamia, Sumerian and Akkadian, originally denoting a dignity).

- ↑ Talmud, Sotah 42a

- ↑ Yiddish Language. MustGo Travel

- ↑ Jewish Surnames Adopted in Various Regions of the Russian Empire. Avotaynu

- ↑ Laczó, Ferenc. Jewish Questions and the contested nation: On major Hungarian debates of the Nineteenth Century. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 14725886, November 2014, Vol. 13, Issue 3