History hasn’t shared the bounty of names associated with the southbound Underground Railroad to Mexico[1], nor identified the conductors, agents and station masters. The networks of routes to freedom weren’t as plentiful or well defined as those northbound, but they did exist. Uncovering their stories requires tenacity.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Expansion of Slavery

As the cotton industry expanded into new territories, demand grew and the domestic slave trade experienced tremendous growth. A series of statutes and penal codes were enacted in various states to regulate the activity and conduct involving slaves and free people of color. The Louisiana Purchase[2] added Creoles[3] and French settlers to the U.S. population. Growing demand for sugar, coffee, tobacco, and cotton led to more slaves to cultivate the cash crops.

The 1808 Act to Prohibit the Importation of Slaves[4], prohibited bringing slaves into the U.S. from foreign entities and the sale of slaves to others outside the U.S. Consequently, slaves were transported from U.S. coastal ports along the Atlantic to ports along the Gulf of Mexico. The major slave ports becoming Galveston, Texas, New Orleans, Louisiana and Mobile, Alabama. Detailed manifests documented these voyages from the port of departure to the port of arrival.

Continued expansion west and southwest created both political and geographical discord between pro and anti-slavery states. The Missouri Compromise of 1820[5] was an important point in history but did not solve the problem. When new territory was added as a result of the Mexican War, the question of whether that territory would be slave or free arose again.

The Genesis of the Southern Route to Freedom

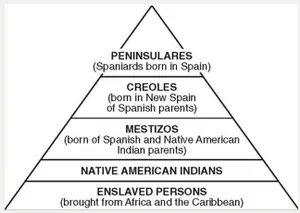

During Spain’s occupation of Mexico, generations of mixing and inter-marriage between Mexicans, Spaniards, Indigenous peoples and Africans took place. The Spaniards adopted a Casta System[6] to rank the purity of race and religion. By the 16th century the Spanish colonial population was made up of three basic groups, the indigenous Indians, European-born Spaniards or their American born descendants called criollos, and Africans, some free, some indentured and some enslaved. This system of ranking lavished freedoms with all of its benefits on some while restricting the rights and penalizing others.

Spain’s 300-year occupation of Mexico has a lot to do with why Mexico became an ally of the runaway slave. Upon gaining independence from Spanish rule in 1821, Mexico immediately began implementing measures against slavery and completely abolishing it in 1829.

For those that were pro-slavery, especially in the Texas Territory, then part of Mexico, giving up their enslaved was out of the question. This culminated into the Texas Revolution[7] with Texas winning their independence from Mexico and forming the Republic of Texas in 1836. The Constitution of Texas[8] made slavery legal again. Slavery remained legal when Texas joined the U.S. as a state in 1845. Ultimately, the agreement made the Rio Grande (called the Río Bravo del Norte in Mexico) the boundary line between Texas and Mexico.

A Clear Path to Freedom is Born

A large portion of Texas bordered the Rio Grande which flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas also bordered the Gulf of Mexico, making it a water escape route for the enslaved.

The proximity of Mexico to the states with legalized slavery and those sympathetic to slavery made the southern route most important. Slave ports in the southern region brought in hundreds of thousands of enslaved individuals, some even after slavery was deemed illegal.

Legislation Makes Capturing Runaways Financially Lucrative

In 1843, the 1st Session of the 8th Texas Republic Congress, approved an act supplementary to an act regulating the sale of runaway slaves. The highlights are below:

The law allows that any person who apprehends and jails a runaway slave west of the San Antonio River is entitled to a reward of fifty dollars per slave. The reward contingent upon the safe return of the slave to their owner or the owner’s authorized agent.

The law allows a person who apprehends and delivers a runaway slave to the owner’s residence to demand an additional payment of two dollars for every thirty miles traveled, in addition to the previously specified reward. This distance is calculated based on the shortest route traveled. In each case, the slave catcher retains a lien on the slave until the payment is made.

On October 6, 1864, during Alabama’s General Assembly in the 4th Annual Session they also strengthened their ability to retrieve runaway slaves by implementing a provision making it financially lucrative. The inherent problem in such laws is that slave catchers looked for any dark body to turn in. This resulted in hundreds of thousands of free people of color being kidnapped and sold into slavery.

Court Records Also Tell the Story

Enslaved people continued to risk their lives to seek freedom. Texas court records are rich with cases of lawsuits brought by the State against citizens accused of harboring or otherwise assisting runaway slaves. The enslaved person represented economic value through their free labor, value in the case of a sale and use as collateral in legal transactions, making getting them back paramount. In a slave-based economy such as Texas, nearly all of the slave holders’ personal wealth was derived from the economic value of his or her enslaved people.

In the 1847 Fall Session of the County of Gonzales District Court the following was recorded as Final No. 267. The State of Texas v. Thomas J. Lambert charged with harboring a Negro slave named Shadrick for a period of two months, although known by the defendant to be the property of David Woodward. The judge decreed the following to the County Sheriff: “You are hereby commanded to take the Body of Thomas J. Lambert if found in your County, and him safely keep, so that you have him at the Honorable District Court, now sitting in and for said County, at the Court house thereof in the Town of Gonzales, there to answer an Indictment exhibited against him…”

The 1858 Gonzales County Court Probate Records document a petition by Nancy Mathews, administrator of the Estate of Wm Mathews asking the Court for permission to sell the Negro man Peter who ran away upon the death of his Master Wm. He was captured and returned while making his way to Mexico. She expects he will escape again, depriving the estate of a valuable asset. This request would allow the estate to benefit from his sale, leaving the new buyer holding the bag should Peter escape again.

The 1860 Marshall County, Texas Court Records held many entries for The State of Texas v. J. B. Stroud. Four of which were the charge “harboring a Negro slave”.

The Matagorda County Probate Records for the Estate of C. K. Reese contain a receipt dated July 20, 1862, for $10 paid to E. H. Cox for returning a runaway slave.

These records provide names as well as details of location and circumstances important to the researcher, allowing for movement toward the reconstruction of an otherwise unknown life of an enslaved person. It also points to the political and social climate of the time.

Moral Consciousness

There were those who showed compassion for the plight of the runaway, some in unexpected ways. At various times throughout history and from people of different stations in life, there existed moral consciousness. The following are just three examples found in the records.

Mexico was once part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, aka New Spain, a political unit of Spanish territories in North America and Asia-Pacific. A vast portion of land included today’s Florida, American southwest, northwest and west. Bartolome de las Casas[9] is cited as being the most famous protector and advocate of non-Caucasians enslaved in the Spanish empire, which as shown by the map included Mexico.

Virginia born slave holder Sam Houston[10], the first president of the Republic of Texas and a hero because he led the Texas Army to defeat Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. Even after becoming the first Governor of the Republic of Texas in 1859, he took a controversial stand against secession from the Union, refusing to side with the Confederacy, eventually costing him his governorship.

One Texas citizen reported the following: “…some low mean white men principle such who before and during the war made their living by training blood hounds and running runaway negroes with them for such planter as would hire them for that purpose”.

Newspapers Offer Insight into the Times

Publications of the era are rich with information of the political, economic and social climate of the times, preserving history for the researcher to discover. Research should not be restricted to the local community because the question of slavery was a national one and many publications across the nation had a wide readership and distribution.

Texas newspapers carried on a regular basis, ads about runaway slaves and the identities of those involved. Filled with details to unravel the identities of the runaway such as name, sometimes detailed descriptions, slave ownership and location, these ads can aid the compiling life story for the enslaved.

Each county had its worries and newspapers such as the Galveston Weekly, the Texas Advertiser and the Texas State Gazette provided a vivid picture of what was going on. Each ran accounts of runaway activity in their communities even carrying accounts taken from other publications. For the researcher attempting to uncover what happened to their ancestor, they are a must read.

The San Antonio News provides an example of an ad describing a Negro boy called Antrum who identified his master as John T. Cameron of Milam County, Texas. The ad is run in more than one publication in hopes of the owner seeing it and coming forward to pay fees and take possession. It also demonstrates the opportunity for profits by local sheriffs eager to get involved, not only to uphold the law but to collect revenue.

These ads are filled with priceless information to help unravel the identities of the runaway such as name, detailed descriptions, slave owners and locales. These ads can aid the diligent researcher in compiling a life story for the enslaved.

Texas Slave Narratives

Under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal[11] and part of the WPA Federal Writers’ Project[12] (1936 to 1940) writers were employed to capture vivid life stories of Americans who lived at the turn of the century. Due to the timing, many formerly enslaved were still alive enabling the documentation of slave narratives including the accounts of escape to Mexico.

Capturing the memories of those who lived through the trauma of the American Slave Era through the Slave Narratives has brought new depth to an often one-sided or untold story of the horrors of slavery. It provided a humanity and vulnerability others tried to erase it. The narratives tell of the heartbreak of family separation, the sexual exploitation and abuse of black women, often in front of their men. The narratives tell of the inhumane workload and treatment. At the same time, they show a race of people, by their very existence, who are resilient, loving, intelligent and on whose backs the foundation of America was built. History has demonstrated that the African descended people’s rich history in America is woven with blood, grit, determination and spirituality.

Combining all of the resources found in legislative acts, court records, newspaper accounts and Slave Narratives, help shed light on an America that should never again exist.

See also

Explore more about the Underground Railroad South to Freedom in Mexico

- Burnett, John. A Chapter in US History Often Ignored: The Flight of Runaway Slaves to Mexico. NPR. All Things Considered. February 28, 2021.

The Slave Trade in the Gulf of Mexico: The Potential for Furthering Research through the Archaeology of Shipwrecked Slave Ships. David Moore. *Presented at Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C. 2016 ( tDAR id: 435069)

- Barcia, Manuel and Harris John. The Slave Trade Continued Long After It Was Legal - With Lessons for Today. HNN. History News Network.

- History. The Little-Known Underground Railroad That Ran South to Mexico. Becky Little. https://www.history.com/news/underground-railroad-mexico-escaped-slaves. Updated August 30, 2023.

- Smithsonian Magazine. South to the Promised Land. July/August 2022.

- Baumgartner, Alice. USC Today. How Mexico Offered Freedom to the Enslaved people of the Antebellum South. September 23, 2021.

- SPLC.org. Descendants of last slave ship arriving in US share history with students | Southern Poverty Law Center (splcenter.org)

- Baumgartner, Alice L. South to Freedom. Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to Freedom.

- Smithsonian. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Africatown Alabama, U.S.A. | National Museum of African American History and Culture (si.edu)

- East Texas Digital Archives. https://digital.sfasu.edu/digital/collection/RSP

- The Slave Economy. https://historymaking.org/textbook/exhibits/show/slavery/economy

References

- ↑ https://www.history.com/news/underground-railroad-mexico-escaped-slaves

- ↑ https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/louisiana-purchase

- ↑ Creole | History, Culture & Language | Britannica

- ↑ (1808) An Act to Prohibit the Importation of Slaves into any Port or Place Within the Jurisdiction of the United States • (blackpast.org)

- ↑ Missouri Compromise: Date, Definition & 1820 ‑ HISTORY

- ↑ Understanding the Mexican Casta System: A Historical and Cultural Perspective — Indigenous Mexico

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/topic/Texas-Revolution

- ↑ https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/constitutions/texas-1845-en/article-8-slaves

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bartolome-de-Las-Casas

- ↑ https://sam-houston.org/controversies/slavery/

- ↑ New Deal ‑ Programs, Social Security & FDR | HISTORY

- ↑ About this Collection | Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1938 | Digital Collections | Library of Congress (loc.gov)