Step 1: Gather and Organize Known InformationStep 1: Gather and Organize Known Information

Begin with what is already known about the ancestor. Collect names, dates, and locations related to the ancestor. Use family records, stories, letters, and any prior research as a starting point. Even small details can provide clues for further investigation.

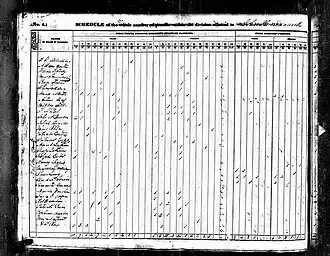

Step 2: Understand the the Pre-1850 US CensusStep 2: Understand the the Pre-1850 US Census

The first U.S. Census was conducted in 1790 (and every ten years thereafter), it initially listed only the heads of households by name, with all others represented as tally marks by age, gender, and race. Here’s how to make the most of these early census records:

- Identify Head of Household: This will give the name of the family leader at the time.

- Interpret Tally Marks: By counting the tallies, estimate the family’s composition—children, spouse, or elderly relatives.

- Cross-Reference with Other Data: Since early census data is limited, use other records to fill gaps.

Step 3: Explore Land RecordsStep 3: Explore Land Records

Land records are some of the most valuable resources for tracing ancestors in early America. The federal government began issuing land grants and homestead records in the 18th century. Key steps for utilizing land records:

- Locate Land Grants and Deeds: Look for land ownership documents in county courthouses, state archives, or the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office Records.

- Analyze Neighbors: Ancestors often lived near family members or other community members who migrated together. Check neighbors' names for potential family connections.

- Use Land Surveys and Maps: These can offer clues about an ancestor’s social circle and migration patterns.

Step 4: Use Military RecordsStep 4: Use Military Records

Many men in early America served in wars, and their service generated records. Important wars before 1850 include the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and various Indian wars. These records can provide valuable insights:

- Revolutionary War Pensions and Bounty Land Warrants: Veterans were often granted land as compensation. The National Archives and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) Library hold collections of these records.

- Service Records and Muster Rolls: These documents list names, ranks, and units, which can lead you to more information about an ancestor's life.

Step 5: Research Probate and WillsStep 5: Research Probate and Wills

Wills and probate records can reveal family relationships, financial status, and property details. Here’s how to utilize them:

- Locate Probate Records: Start with county courthouses or state archives. FamilySearch has extensive probate record collections.

- Analyze Heirs and Executors: Wills typically name children, spouses, and even in-laws, which helps construct family trees.

- Consider Guardianship Records: If an ancestor died young, guardianship records can reveal connections with other family members or neighbors.

Step 6: Delve into Church and Cemetery RecordsStep 6: Delve into Church and Cemetery Records

Before widespread civil registration, churches documented vital events like births, marriages, and deaths. Here's how to access these records:

- Identify the Religious Affiliation: Determine if the ancestor was part of a specific denomination. Different faiths kept records in various ways.

- Look for Baptism, Marriage, and Burial Records: Church archives, especially those kept by Catholic, Lutheran, and Presbyterian congregations, are often rich with information.

- Search Cemetery Records and Gravestone Inscriptions: Websites like FindAGrave and BillionGraves have extensive records, often providing dates and family names.

Step 7: Investigate Newspapers and Local HistoriesStep 7: Investigate Newspapers and Local Histories

Though sparse, newspapers, and local histories can contain obituaries, marriage announcements, and community news relevant to your ancestor:

- Local Newspapers: Many early American newspapers are digitized and searchable through platforms like Chronicling America and OldNews.

- County Histories: These books often include biographical sketches of prominent families. Libraries and historical societies frequently have copies of these histories.

Step 8: Consider Tax and Voting RecordsStep 8: Consider Tax and Voting Records

Tax lists and voting registers provide indirect evidence of an ancestor's residence, age, and landownership:

- Tax Lists: These often list the taxpayer’s name, property details, and payment amount. They can serve as a substitute for missing census data.

- Voting Records: Voting eligibility records may list male ancestors over age 21, providing clues about residency and citizenship.

Step 9: Study Migration and Settlement PatternsStep 9: Study Migration and Settlement Patterns

Many early settlers migrated in groups or followed specific trails, such as the Great Wagon Road or the Oregon Trail. Understanding migration patterns can be key:

- Examine Known Migration Routes: Look for migration paths associated with an ancestor's region.

- Follow the “FAN Club” Approach: This technique involves researching the Friends, Associates, and Neighbors of an ancestor, as these people often migrated together.

Step 10: Join Genealogy Societies and Online CommunitiesStep 10: Join Genealogy Societies and Online Communities

Membership in genealogical societies or joining online forums can lead to new discoveries:

- Join Relevant Historical Societies: Local societies often have exclusive resources, such as unpublished manuscripts or volunteer experts.

- Utilize Online Databases and Forums: Sites like MyHeritage, FamilySearch, and others offer searchable records and active communities.

ConclusionConclusion

Tracing pre-1850 ancestors can be challenging, but persistence pays off. Be methodical, and be open to exploring indirect sources. Even if the records are sparse, piecing together clues from multiple sources can reveal a compelling story of your early American heritage.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

See alsoSee also

Learn more about how to trace pre-1850 U.S. AncestorsLearn more about how to trace pre-1850 U.S. Ancestors

- Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office Records - United States Bureau of Land Management

- Decennial Census by Decade - United States Census Bureau

- They Had Names: Identifying Children Represented by Tick Marks in Pre-1850 Censuses - MyHeritage