German given names and the understanding of their origins, phonetics, patterns, and idiosyncrasies can greatly aid when researching for German ancestors.

It is important, however, to keep in mind that German is a pluricentric language with many dialects whose grammatical and orthographic rules were standardized in a process that lasted several centuries; this process was completed as late as 1901 with the adoption of the Duden Handbook as the standard in Germany, which was later adopted also in Austria-Hungary and Switzerland. As a result of this long evolution, given names can have many different forms varying from one region of the Germanosphere to another.[1][2]

History of German given names

A significant number of the given names in Germany were derived either from Old High German, like Adelheid, Lothar and Inga, or from biblical sources like Jakob, Matthias or Margaretha. During the Age of Enlightenment, it became customary to assign during baptism a vorname (forename) to be used as a "default" first name and then at least another middle name, which was the name the baby would be known; for boys, the first name was generally Johann or Hans, and for girls, Anna or Maria. One of these vornamen, usually the second name, was intended for everyday use and known as the Rufname (lit. "call name"). This name is often underlined on official documents, and known as the preferred given name of the person for their daily use since childhood. An example would be the German philosopher Julius Frauenstädt, who was registered as Christian Martin Julius Frauenstädt on April 17, 1813, in Bojanowo, Prussia (today part of Poland). It is important to keep this in mind when researching German ancestors, as not knowing this may lead many people to believe that all siblings are the same person.

Since the late 1500s, it became customary among German nobility to give a large number of given names to children, often more than six names; this custom soon extended to the bourgeoisie class and became the norm until the end of the 19th century. Nowadays, more than three forenames are rare. Roman Catholics often used names from the Catholic sanctorale, while most Protestant Germans also used names from the Old Testament or even pre-Christian mythology.[3]

Shortened German given names

A peculiar aspect of German given names is the common use of shortened versions of given names; names in which the first syllable is clipped off, instead of the last syllable as is the case in English; some examples of these unusually shortened names are:

- Klaus (Nikolaus)

- Bastian (Sebastian)

- Mannes (Hermanus)

- Stina (Christina)

- Trin (Katharina)

- Lena (Magdalena)

- Mina (Wilhelmina)

- Kim (Joachim)

- Henny (Johanna)

- Hannes (Johannes)

- Trina (Catharina)

- Sepp (Josef)

- Greta (Margaretha)

- Lina (Carolina)

Inheritance patterns of German given names

Unlike in other places in Europe, German names do not follow a specific pattern; however, some villages and small towns had the following pattern for assigning names to children, based on their baptismal sponsors, which could be a close relative, a good friend of the family or even the midwife who assisted with the birth of the baby:[3] first son for paternal grandfather; second son for maternal grandfather; third son for father; fourth and subsequent sons for the great-grandfathers; the same is done to assign names to the daughters. When a child died, their name was often given to the next newborn baby of the same gender, which can be potentially confusing when exploring an old German family tree because the same exact name may appear repeated a number of times.[4]

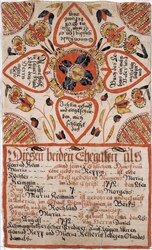

German given names in birth certificates from Pennsylvania

The Taufschein ("birth and baptism certificate") is unique to Pennsylvania German culture. Even though decorated manuscripts were common throughout Europe, they neither combine birth and baptism in one document, nor included biographical information about the child and their parents, which makes Pennsylvania German Taufschein unique and very valuable for genealogists. With the mass arrival of Germans to Pennsylvania in the late 1700s, they brought the tradition of printing birth and baptismal certificates with them, with blank spaces to be filled in by scribes to personalize the documents; however, these printed certificates were commonly illustrated with colorful patterns. These documents became as precious as family jewels and contain priceless information like the name of child, birth date, baptismal date, city of town of birth, name of the parents as well as the mother's maiden name, and sometimes even the pastor's and witnesses' names.[5]

Explore more about German given names

- Historical records from Germany on MyHeritage

- German Names and Naming Patterns by James M. Beidler at Legacy Family Tree Webinars.

- The Pennsylvania-German in the Settlement of Maryland record collection at MyHeritage

- Pennsylvania-German Society, Volume 16, 1907 record collection at MyHeritage

- Pennsylvania-German Society, Volume 10, Part 2, 1900 record collection at MyHeritage

- Pennsylvania-German Society, Volume 3, 1893 record collection at MyHeritage

- Germany, Hesse Emigrants record collection at MyHeritage

- Germany, Emigrants from Southwestern Germany, 1736-1963 record collection at MyHeritage

- West Prussia Church Books record collection at MyHeritage

- Germany, Births and Baptisms, 1558-1898 record collection at MyHeritage

- Germany, Marriages, 1558-1929 record collection at MyHeritage

- Germany Deaths and Burials, 1582-1958 record collection at MyHeritage

References

This article was adapted from German Names and Naming Patterns, a webinar presented by James M. Beidler on Aug. 26, 2015. Watch the full webinar on Legacy Family Tree Webinars.

- ↑ GERMAN AND ITS NORMS. Goethe Institut

- ↑ 10 facts that help explain the German language

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 German Naming Traditions Genealogists Should Know. Family Tree Magazine

- ↑ German Naming Conventions. Santa Clara County Historical & Genealogical Society

- ↑ About the Pennsylvania German Fraktur Collection. PennState University Libraries