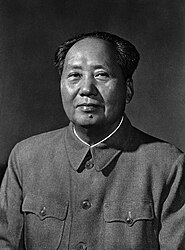

The Chinese Cultural Revolution was a movement which began in communist China under the rule of Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted in one form or another down to his death in 1976, though the most intense period of it was during the first years in the late 1960s. On the surface of it, the Cultural Revolution was launched as an effort to purify Chinese society of its allegedly capitalist, bourgeois and anti-communist elements. In reality it also served more as a means for Mao to strengthen his control over China after his position had been weakened as a result of the disastrous ‘Great Leap Forward’ of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Cultural Revolution saw wide-ranging violence across China which by some estimates killed as many two million people over the decade. It also had implications for Chinese migratory patterns and demography, as the Cultural Revolution placed an emphasis on sending millions of Chinese people from the towns and cities into the countryside to be ‘re-educated’.[1]

Chinese Cultural Revolution chronology of events

The Chinese communists emerged victorious in 1949 from China’s long-running civil war with the Kuomintang or Chinese nationalists. With victory and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong became the most powerful individual in China as Chairman of the Communist Party of China between 1943 and his death in 1976. However, in the early-to-mid-1960s his position was weakened somewhat in the fallout from the ‘Great Leap Forward’. This had been an initiative which was initiated in 1958 to accelerate China’s industrial growth rapidly so that it would catch up with Britain’s economy within a half a decade, particularly in steel production. Efforts to do so resulted in a catastrophic man-made famine as the government prioritized industry over agriculture and farm implements were even melted down by over-zealous regional officials anxious to meet their quotas of steel production. Famine set in during 1959 and eventually by the time the Great Leap Forward was abandoned in the early 1960s tens of millions of people had starved to death in China.[2]

In 1966 Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in large part so that he could reconsolidate his control over China. On the 16th of May that year he issued what is now known as the 16 May Notification in which he informed the country that “representatives of the bourgeoisie” had infiltrated the government, army and virtually all walks of Chinese life.[3] In the days and weeks that followed the national media was utilized to galvanize the Chinese population to purify society of these “representatives of the bourgeoisie” by rooting out any enemies of communism and creating a more socialist state. The result was a huge wave of violence over the next two years as ‘Red Guards’, gangs of communist ideologues, many of them being students and younger people, roamed the cities and towns attacking anyone who seemed to present the possibility of secretly being an enemy of the communist movement.[4]

This Cultural Revolution saw vendettas being settled under the cloak of acting on Mao’s injunctions. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed in violent attacks between the summer of 1966 and the end of 1968. Thereafter the government began to rein in the Red Guards, but some had become unmanageable and in the end it was well into the 1970s before the full excesses of the Cultural Revolution were brought under control. In order to bring it to an end Red Guard units were broken up and millions of students and young people who had been involved in them were sent to the countryside for ‘re-education’.[5]

Extent of migration during the Cultural Revolution

By the early winter of 1968, as the government sought to bring the Red Guards under control and end the worst of the violence, Mao and his ministers came up with a new policy. This was based around the slogan “Up to the mountains and down to the village.” By this the government planned to send huge numbers of people out of China’s cities and towns into rural areas, i.e. the mountains and villages, to be re-educated and to emerge as more pure communist proletarians in the long run. The policy was founded on the fact that Mao was himself born and raised in the countryside and many of the leading communist figures had spent years living in rural areas during the Chinese Civil War. As such, they believed that periods of time in the countryside would help rebuild the characters of those sent their. In total, it is believed that as many as 17 million people were sent from China’s urban centers to the countryside in the first half of the 1970s for re-education.[6]

Demographic impact of the Cultural Revolution

The demographic impact of the Cultural Revolution was huge. In a bizarre overturning of traditional communist values, it fostered the movement of people from the cities to the countryside and so expanded the rural population at the expense of the urban proletariat in the 1970s. Consequently, the Cultural Revolution led to a temporary pattern of de-urbanization in China, though this process was completely overturned in the last quarter of the twentieth century as China’s economic miracle saw a rapid flight back to the cities. However, the long-term impact of the policy on people psychologically and socially has been studied over a period of decades and appears to have been profoundly negative.[7]

Another less noted element of the period was a growing awareness within the government in the early 1970s, as the “Down to the village” program was underway, that China’s population was growing at a somewhat unsustainable level. The scars of the Great Leap Forward had created residual fears of a new famine if the country’s population exploded upwards. Therefore, while it is somewhat improperly understood, the origins of China’s ‘One Child Policy’ are in many ways found in the early 1970s while the Cultural Revolution was still underway, as measures like the ‘Later-Longer-Fewer’ policy, which advocated for restricting families to having two children, were fostered from the early 1970s onwards.[8]

Explore more about the Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Genealogy: An Introduction to Jiapu 家譜 (Chinese Genealogy Records) at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Chinese American Research: Challenges and Discoveries at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- A tragedy pushed to the shadows: the truth about China’s Cultural Revolution at The Guardian

References

- ↑ Frank Dikotter, The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962–1976 (London, 2017).

- ↑ https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/11/the-cultural-revolution-50-years-on-all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-political-convulsion

- ↑ https://multimedia.scmp.com/cultural-revolution/?src=amp-article-text

- ↑ https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/from-red-guards-to-thinking-individuals-chinas-youth-in-the-cultural-revolution/

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/19/tragedy-pushed-to-the-shadows-truth-about-china-cultural-revolution

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X1530108X

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304387821000432