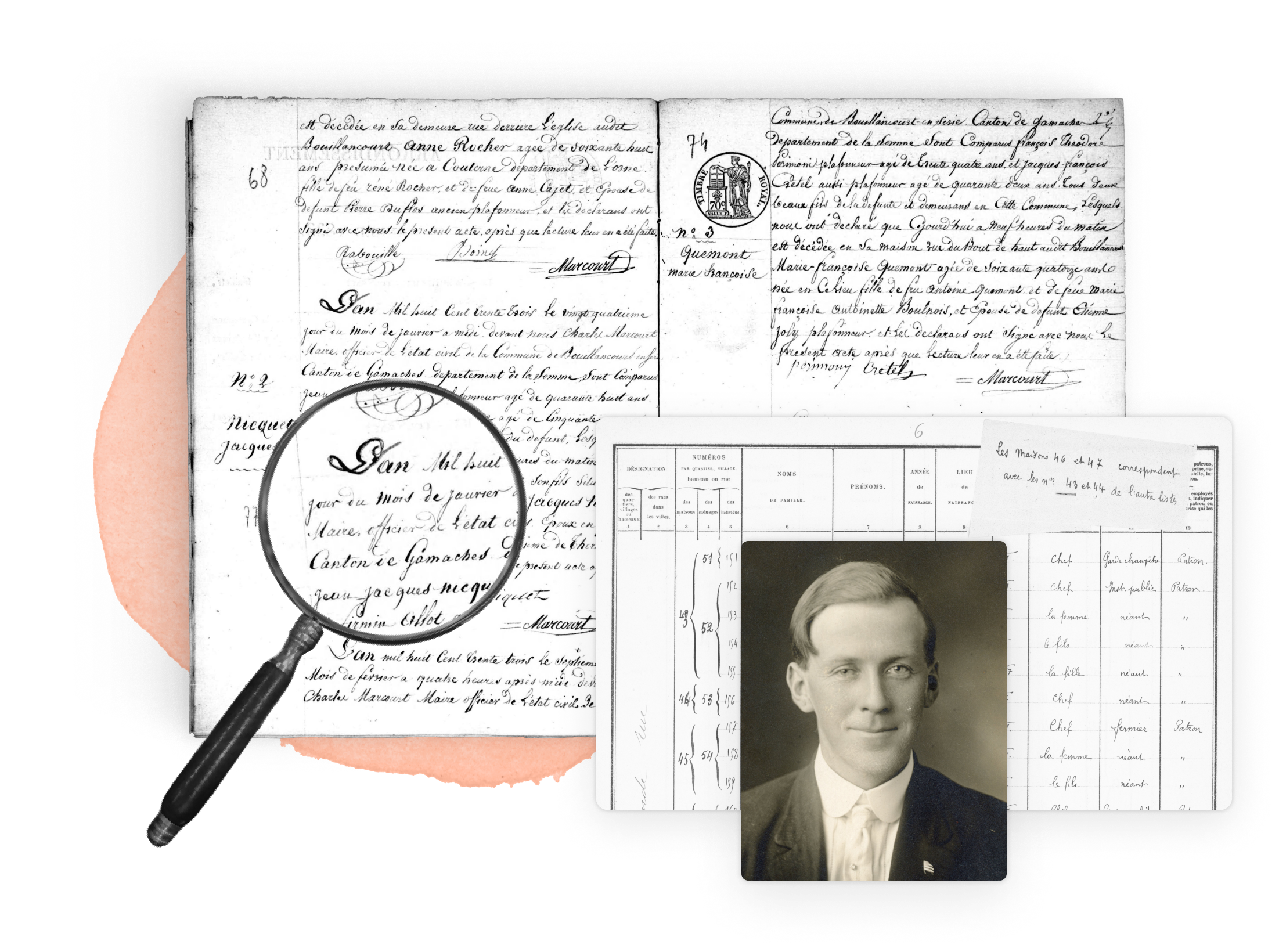

The scarcity of documentary sources for the 18th and early 19th centuries, partly because of the non-existence of census material and partly due to the destruction in 1922 of most of the public records of Ireland, made it necessary to seek substitutes for the destroyed records and to make them accessible for research.

Freeholders' registers and poll books are one such substitute resource and are, therefore, of particular value to historians, perhaps for analysing voting patterns or the strength of the tenant electorate on estates. Freeholder Lists are a rare and valuable resource, especially for pre-famine research. Freeholders were men who either owned their land outright or who held it in a lease for the duration of their life, or the lives of other people named in the lease.

Land tenure in Ireland was classed as either freehold or leasehold. A tenant farmer could have been a freeholder, a leaseholder, or a tenant at will. A freehold could be held either "in fee" meaning outright ownership, or as a lease for an indefinite period of a life or a number of lives (e.g. three lives, roughly 31 years each). A leasehold was a lease for a definite, fixed period (e.g. 9 or 14, or 31, or 99 years). A tenant at will had no security of tenure.[1]

Freeholders' records list freeholders who were entitled to vote and those who did vote at elections. They are arranged on a county basis as two main types:

- registers - details of those who had registered to vote

- poll books - lists of voters and the candidates for whom they voted[2]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

The Importance of Freeholders records

Before the 1872 Ballot Act, voters had to publicly declare their allegiance, which could lead to landlords putting pressure on their tenants to support their chosen candidate. The people allowed to vote also changed through this period, notably with only Protestants with a freehold of at least 40 shillings a year able from 1727 to 1793, both Protestants and Catholics with 40 shilling freeholds could vote from 1793 to 1829. After 1829 the rate was increased to 10 pounds, removing the right to vote from all 40 shilling freeholders and confining the electorate to those with considerable property and money.[3]

An ordinary applicant (small-medium farmer) would apply based on holding (or having a shared interest) in a £10 freehold in their townland of residence. The gentry (whether resident or not) would typically apply based on having a £50 freehold in any county.

Each applicant gave the address of the freehold (by townland, parish, barony) and residence if different. They would cite whether the freehold was for land, and/or a house (only the head of household would claim for "house and land"). Where a number of sons/ brothers were also named on these "lease for lives", they would apply to claim their freehold interest in that same "land" in the home townland. Some farmers held leases of land only in townlands outside their own parish, which can suggest points of earlier origins, or that they were middlemen.[4]

Using Freeholders records

Freeholders’ records provide a range of information about land ownership and may contain all or some of the following:

- name of freeholder

- address of freeholder

- location of freehold

- description of freehold

- name of landlord

- address of landlord

- value of freehold

- names of other lives

- date and place of freeholder’s registration

- occupation of freeholder

- religion of freeholder

Be aware that not all records survived in their original form - some are saved as transcripts, manuscripts or printed copies.[5]

Finding Freeholders records

Records for Ulster Freeholders can be found through the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) or at MyHeritage.

PRONI's freeholders project entailed the digitisation of about 5,500 sheets from pre-1840 registers and poll books, and the provision of an index of names linked to the high-quality digitised images. There are also a number of other websites which have indexed and digitised records of Freeholders for individual counties. For example, the Ulster Historical Foundation has a database containing the names of clergy and freeholders of County Monaghan in 1852.[6]

Explore more about the Ulster Freeholders

- Ireland, Ulster Freeholders record collection at MyHeritage

- Northern Ireland collection catalog at MyHeritage

- Ireland collection catalog at MyHeritage

- Irish Genealogical Records in the 17th-19th Centuries webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Foundations of Irish Genealogy 5: The Major Records IV, Nineteenth-Century Property Records webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ https://irelandxo.com/ireland-xo/news/8-faqs-about-irish-freeholder-lists

- ↑ https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/about-freeholders-records

- ↑ https://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-20218/ireland-ulster-freeholders

- ↑ https://irelandxo.com/ireland-xo/news/8-faqs-about-irish-freeholder-lists

- ↑ https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/about-freeholders-records

- ↑ https://ulsterhistoricalfoundation.com/genealogy-databases/clergy-and-freeholders-monaghan