Exploring ancestral roots involves delving into the locations where ancestors resided and investigating their migrations, understanding the impact of their surroundings on their lives. Throughout the research journey, genealogists often encounter challenges related to the geography of these ancestors, including navigating changing boundaries and unfamiliar languages.

As listed below, there are many factors and resources to consider when researching geography.

Historical and political boundariesHistorical and political boundaries

Researchers unfamiliar with a geographic region will often make this mistake: assuming that the current geographical boundaries for a county, province, state, or county are the same boundaries used when an ancestor lived there.

Over time, boundaries changed often due to war or conflict. The winning country would often annex the losing country and even change the name of the region.

Other changes occurred when regions merged or split such as provinces in Canada and counties in the United States. In addition, when a region in the US became a state, the territory would often be renamed. Example: the Northwest Territory became the Indiana territory which became the Michigan Territory which became the Illinois Territory as new states were formed.

To overcome this challenge, determine the boundaries and other geographical elements for when an ancestor lived there. Otherwise, it is common to waste time searching for records in the wrong state or county.

For United States research, consult the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries to determine county boundaries for specific time periods.

MapsMaps

Ever since the human era, there has been a need to understand our world and how we fit in it. Maps were created to show landmarks and locations, where specific clans or families lived, and what enemy areas to avoid.

There are a variety of different maps with different purposes that can assist with genealogy research.

Map information for genealogy researchMap information for genealogy research

Each type of map offers different information about the lands of an ancestor. Here are the best ones to consult:

- Present Day: Review a current map of the location being researched. Understand the boundaries and use this map as a basis for comparing older maps and historical changes over time.

- Census: These maps can help determine the proper enumeration district for an ancestor when indexed searching can’t locate the census record. Also, ward maps were created during specific years and can help pinpoint where an ancestor was at a specific time.

- Data: A relatively new type of map, almost always digital (online) which takes a data set, such as the expansion of slavery in the United States and depicts the data visually plotted against a geographical location. More and more of these “mashups” using “big data” are coming online each day.

- Fire Insurance: Used to note buildings and their structure/composition, these maps also offer detailed descriptions of businesses, houses of worship and more – all helping us to better understand an ancestor’s community.

- Historical: A map showing how an area looked at a specific date or date range. Usually mark events such as statehood or war.

- Land: Used to mark land ownership and how land parcels were determined and disbursed (on a state or federal basis).

- Migration: Understand the various migration routes and modes of transportation ancestors may have used to move from one location to another.

- Military: If an ancestor served in specific military engagements, use these maps to understand their movements and engagements.

- Political: The most common map used by genealogists showing municipalities, names, streets, etc. Check the date of each map and use a date range to note changes.

- Topographical: Also known as relief maps, show how the land looks via terrain, landmarks, features such as mountains, passes, meadows and more. These maps can often explain why an ancestor’s family didn’t attend the closest church due to difficult terrain, etc.

- Transportation: Determine travel routes, track growth of urban areas and understand migration patterns using transportation maps.

How to incorporate maps in genealogy researchHow to incorporate maps in genealogy research

From simply consulting a map in order to visualize an ancestor’s location to actually plotting research data by location, researchers find that including maps in can actually solve research problems and help break down brick walls.

- Check county and other borders. When attempting to locate census and vital records, check to make sure to have the right locality, especially county. County borders changed over time which impacts access to records.

- Review a variety of maps over time. Compare various maps of the same area over the timespan of an ancestor’s life – this is useful if maps designate landmarks, businesses and roads. What was added or removed during that time period? Were locations “renamed” or changed?

- Plot location data for an ancestor. Track where an ancestor lived, worshiped, worked and more using maps. Gain a better understanding as to the “why” of certain things such as “Why did she attend that church?”

- Use maps for cluster research. Cluster research looks for groupings of people with the same surname, or those who are from a specific country or have a common ethnicity. Once identified, research those people for clues related to an ancestor.

- Trace migration patterns. Americans loved to move (and still do). Track migration of a family from one point to another. View the map to see what they encountered on their journey, what hardships they had to overcome and why they settled there.

Migration causes and routesMigration causes and routes

A review of the causes of migration as well as the routes used to move from one location to another, can help understand why ancestors landed in certain places.

Here is a list of reasons why individuals or families migrated:

- Landowning traditions. In some cultures, the oldest son in the family inherited the family land. This meant other sons often had to move to other locations in order to secure land.

- Political and religious freedom. Families would move to other regions and even across oceans in order to secure the freedom to worship as they wanted and the freedom to believe what they wanted.

- Crowded conditions. Certain locations, like the New England region of the United States, had a high population density. Families went westward in search of land.

- Military bounty land. In certain conflicts, such as the American Revolutionary War, soldiers and others who served were awarded plots of land as compensation.

- Better transportation. Over time transportation innovations such as trains, steam boats, automobiles, paved roads, and airplanes allowed for easier migration.

- Economic security. Other lands and regions offered more job opportunities. In addition, land accumulation programs such as the Homestead Act in the United States allowed cash poor families to inhabit and improve large plots of land and eventually own such land.

Migration routes are often documented in country. In the United States, roads and trails often went from east to west.

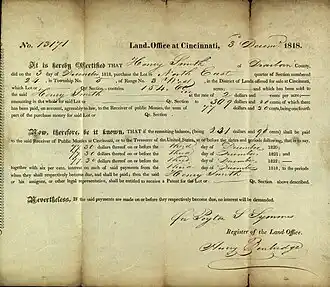

Land recordsLand records

Genealogy researchers need to take time and thoroughly understand the land records used to record the sale or apportionment of land. These include plat maps, deeds, legal descriptions of land, and more. Each country had its own method of record keeping and early records may be difficult or impossible to find.

In the United States, prior to 1900, land was often sold to other relatives, not to strangers. And also consider other "land records" which might actually record a land transaction such as military records (for land bounties), probate records (land inherited by family members), and tax records (property tax on land).

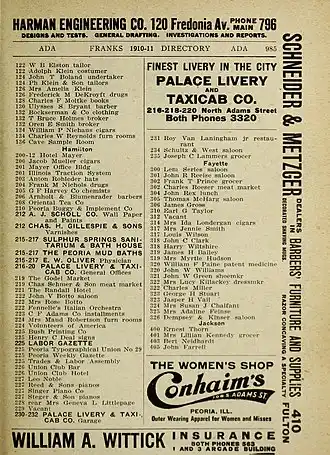

City and business directoriesCity and business directories

The first "directory" appeared in the United States in the mid-1700s and was a simple listing of resident names as well as locations and occupations. Over time, these directories were vital in knowing neighbors as well as the various businesses in an ancestral town or city.

These directories also might list whether a person were widowed, if they were "boarding" or "lodging," and even if they moved to another location since the last edition of the directory.

City and business directories declined after World War II when telephones became more affordable and were replaced with telephone directories which, unfortunately, did not offer as much information.

Cluster researchCluster research

Researchers often have to step away from "bloodline relations" and seek out F.A.N. Club information which often includes geographical clues. "Friends, Associates, and Neighbors" make up these "clubs" and the members are often not related to an ancestor. However, they represent the social, business, and religious circles making up a network that left behind amazing records. Cluster research is almost always based on geography and location.

Effective cluster research means reviewing documents with a keen eye towards "commonality" as in:

- Census schedules: Who else spoke the same language as an ancestor? Who else had the same type of occupation? And who else immigrated from the same country? There may very well be a connection between that person and an ancestor.

- Land records: For a specific piece of property, review the map of plots surrounding an ancestor's land. It could be that a large plot of land was subdivided and sold by an ancestor to others. Keep in mind, land was often sold to a relative and not a stranger.

- Passenger lists: Review the passenger list for an immigrant ancestor and treat them just like census schedules. Look for those who share the same language, the same hometown, the same final destination.

A new location was probably confusing to an ancestor and understanding where they lived, worked, and worshipped can be just as confusing for the researcher. Don't make assumptions as to historical and political borders. Don't forget to understand the various maps available created to document ancestral lands. And seek out records that may at first not appear useful - those non-land records that are filled with clues about where an ancestor came from.

Explore more about how to overcome geographic challenges in genealogy researchExplore more about how to overcome geographic challenges in genealogy research

- American Memory Project – Library of Congress Maps

- Atlas of Historical County Boundaries - The Newberry Library

- Cyndi’s List - Maps and Geography

- David Rumsey Map Collection

- Geographical Names in Canada

- Historic Map Works

- History Pin

- Library and Archive Canada: Map Archives

- Mapping History

- My Maps - Google Maps

- Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

- Pinmaps

- Rootsmapper

- The Atlas of Canada

References