Crypto-Jewish genealogy is different from all others. You are not looking for the family names from the 1800s, you are looking for the names from the 1400s! The Conversos, or Crypto-Jews, changed their names constantly, and the only way to bridge that gap is to go back slowly, meticulously, and with enough tenacity and patience to see the project through. It can be done, but it is a slow step-by-step process that should be followed carefully. The search for Jewish roots through Catholic, Inquisition, and notarial records is a novel idea and pioneer work.

If your family lived for generations in an island nation such as Jamaica, you may be able to find proof of a Jewish lineage easier because of the smaller and close-knit populations However, if your family was Catholic and living in Latin America or Spain, chances are that you will have to make your way back to Inquisition documents to find this lineage as most synagogue and cemetery records were destroyed during the many generations that have passed.

What is Crypto-Jewish genealogy?

Starting in the late 1300s, there were forced conversions of Jews in Spain due to organized massacres, and as a result, large segments of the population became Roman Catholic practically overnight. This continued until the expulsion of all Jews in 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, known as the Catholic Kings, signed an edict which is now known as the Spanish Inquisition, that all Jews must leave their lands or become Catholic and so began an almost 300-year period of Jews pretending to be Catholic while practicing their Jewish beliefs underground in secret trying to hide from the Inquisition. Their original Jewish names were lost to them as they took on Spanish names and often used aliases. This large group of people was originally known as the Marranos and today is mostly known as New Christians, Conversos, or Crypto-Jews. In Hebrew, they are known as Bnei Anusim. Marranos is no longer widely used as the word means pig and is highly pejorative. The Inquisition followed the Spanish conquests in the New World, and the same situation was created in the Spanish Colonies of Mexico, Peru, Colombia, and many others.

Following along the same lines was the Portuguese Inquisition, established in 1536 and also followed the Portuguese land conquests to create this situation in Brazil, India, and many other countries. The Spanish Inquisition continued until 1834 and the Portuguese Inquisition until 1821, thus creating a very difficult landscape of changed names and identities in the Iberian Peninsula and beyond. Below is a map on how to navigate this situation from a genealogy standpoint.

Some important history about Crypto Jews

See also: How to research ancestors who changed their names

To start, it is important to understand a little about the history of the Iberian Peninsula and its relationship with the Jews. A rudimentary understanding of the migration patterns and the different periods of conversions is necessary. The history of the Jews in Spain and Portugal is a complex one. The Jews were marginalized centuries before they were expelled, and the planned massacres led to mass conversions in 1391. More or less on this date, the Jewish names were lost and the Crypto-Jewish Spanish-Portuguese names began. You will be searching for Spanish names and families from this period forward.

The reason we are able to find Crypto-Jewish lineages at all is because the Jews still practicing the Jewish religion in hiding were being caught by the Inquisition and those are the records that we are hunting down. If they did not go underground to pray and were true Catholics, chances are you will not find any trace of them as being Jewish.

When the Jews converted to Catholicism, they were baptized, and they took on new surnames. Many of them took names of famous Catholic mayors or officials; some took on the names of their Christian neighbors; and still, others were given topographic names or places. Names such as Ramos, or Flores (bouquet of flowers), Guerra (war), Almendra (almond), and many others that are now typically Spanish last names are traced back to this time in history. Still, others took names of villages or towns and even of mundane objects such as Cuchillo (knife) or Manzana (apple). Depending on the dates they converted, they may or may not have kept their original names. Most did not, but they may have kept a variation. For example, the name Perez may have turned into Piriz, Pires, or even Priz.

One of the difficulties of researching the family names is that at certain times in history, people were changing their names constantly and using aliases. For example, if someone converted in 1391 and took the name Ramos, they would use this name for several generations. Then at some point, if a family member would get caught practicing Judaism secretly, and they would start using the name Martin. If Martin got caught by the Inquisitors, the family would start using another surname, such as Peña, and so on. It is important to keep close track and only trust primary sources to follow along with no errors.

This is just one example of a name change, but it happened all the time and in every family that was in hiding as they practiced the Jewish religion. For two hundred years or so in Spain and in Portugal, names were changing continuously. This is why it is crucial to follow generation after generation, with actual documents showing birth, marriage and death. To skip a generation would mean there would be no certainty whatsoever that you are tracing the correct lineage. It is important to note at this time that it will be highly unlikely that you will be able to find the original Jewish name if your family has been Catholic for over 500 years. You will find the Jewish person at the end of the tree but the actual Jewish name will be much more challenging.

Notarial records many times yield information such as: Juan Ramirez, who used to be known as Yucef Abendana, was in a fistfight in the street today, or it might say Orabuena, who is now known as Maria Ferandes, is asking for the dowry that should have been paid to her. Statements like these are sprinkled throughout the notarial records in Spain, and if you have been able to trace back far enough, you may be lucky to find your original Jewish last name. If the conversion took place in the group from 1391, this will be harder to find.

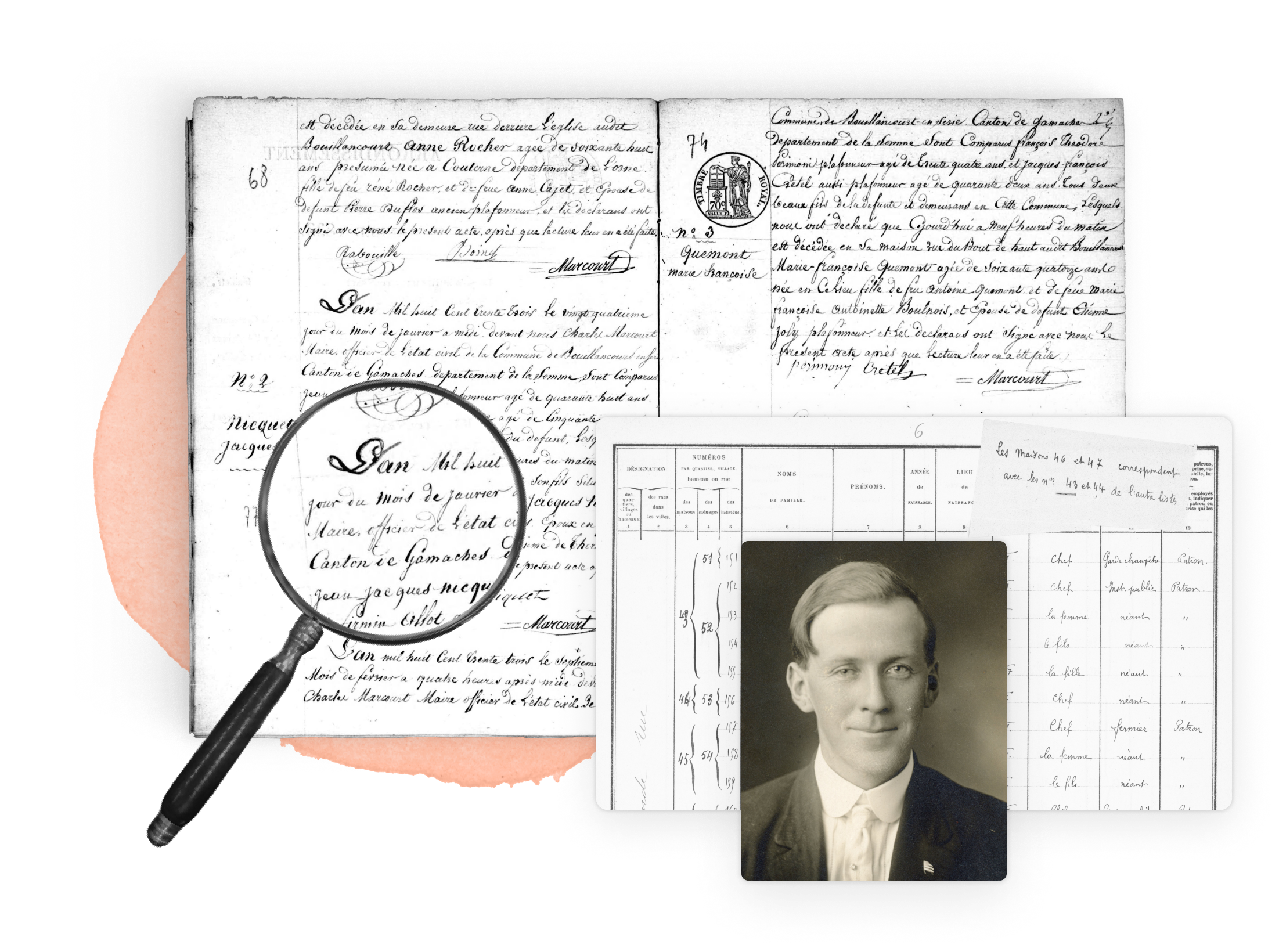

Document gathering for Crypto-Jewish genealogy

Below is a list of documents that could be useful in tracing the clues of your family history. Remember you are usually heading back to a Jewish Lineage via the Catholic Church documents. Find out as much as you can, and ask all family members to contribute the originals or scanned copies of as many documents and pictures as you can get your hands on. It is important to ask the elderly family members first. Do not discard anything you are given. You will not know what is and what is not important for a very long time. Passports, visas, citizenship or other government types of documents, old pictures that show some sort of costume or countryside that will give you clues, journals or family histories written by family members or friends, old family trees that may have been started and never finished are crucial. Birth certificates, marriage certificates, and death certificates as well as baptism, communion or confirmation records, information written in prayer books or inside a bible. After you have gathered all of these documents, you will probably have a lot more information than you originally thought you could amass.

- Pick one grandparent line only to work with to be able to focus on the task as the further back you go, the search becomes more complex.

- Always put the full names that you do know with all of their last names. Go back as far as you can. Continue with dates and places of birth, marriages, death certificates, and as much information as you can gather.

- If you live in Latin America or your ancestry is from Mexico, Central or South America it would be a good idea to look in the special collections on the FamilySearch website to see the Catholic Church records. This is the best way to be able to trace a Catholic relative out of your country until you reach the origin in perhaps Spain or Portugal.

Interviewing family members for documents and family customs

See also: How to gather information from relatives

After you have completed this task, you will need to start seriously interviewing your family members, starting with the oldest ones first. You will want to get genealogy information from them, but you will also be asking about customs and rituals that the family may have had that only the elders will remember. Sometimes you will only have one opportunity to do this, so it is important to get it done correctly the first time.

Make sure that you have given your relative ample time to know that you will be coming over and the reason you want to see them. Ask them to prepare their thoughts and, if possible, notes in advance. Record the conversation and make sure that you ask permission to use it. If it makes the person nervous, then turn it off and take a lot of notes. Bring a hand scanner or a tablet or phone to take good pictures. Do not assume they will allow you to walk out of the house with their precious papers and photographs even if you promise to bring them back. If you need something that is very large, such as a family journal or cookbook, or even a family tree, you can always offer to run to the corner office store, copy it and dash back with the original. If they do allow you to borrow some of these precious records, then always be sure to return them promptly so as to always be able to have access to more material in the future. Bring a list of questions and start with the easy ones such as place of birth and family occupations. Sometimes the floodgates of memories need time to open up. Always date your notes and make sure you have the full legal name of your relative. When interviewing the elder family members, make sure that you write everything down. Do not discount anything said, even if it sounds like ramblings. If your great aunt tells you that your uncles Louis and Charles had daughters named maybe Mariana, maybe Mariela and maybe Maria and then says, “There were always many Mariela’s in our family.” That information is the most important you hear! This is significant because there is so much name repetition in Sephardic Jewish families that you now have one of your single most important clues. You will pay close attention any time you see the name Mariela in old genealogical records.

If you do not understand the names of places or family names that you are being given, do not count on understanding it later with your notes or recording. Ask, ask and ask again for clarification.

Some of the most important and basic questions to ask are the following:

- Start with their full legal name and date of birth, and then find out if they had a nickname or a family nickname

- Place of birth and other cities or countries they have lived

- Dates if possible, and if not, ask them if they remember how old they were when they lived in that town or what grade they were in

- Find out the full names of their parents and grandparents as well as their places of birth, cities lived in and occupations

- Important are the full names of all their siblings. Some may have died at birth or at a young age. Try to prod for as much information on this as you can. Sometimes we find ourselves climbing up a family tree via the siblings if other information is not available

- Names of schools they attended: kindergarten through college. The more information, the better.

- Churches or places where the family worshipped

- Place of baptism, communion and confirmation. An assumption is being made here that the family was Catholic for centuries. If they were NOT baptized, and there was NO communion or confirmation, this is just as relevant to know.

- Citizenship and visa information

- Names of ships they took and dates when migrating from one country to another

- Recollections of family information their deceased spouses may have told them. Sometimes you may be relying on information from one grandparent only

- Occupations held in the family. Maybe the grandparent has been retired for 25 years, but they knew that they came from a family of wine growers for example.

- Any and all information relating to a migration pattern is essential. You should ask if they know if the family name ever changed. This used to happen many times when arriving in a new country and wanting new beginnings. Ask if there is a family crest or emblem that they know of If possible, get a picture or a copy.

- Find out if anyone in the family ever wrote a book or was mentioned in a newspaper. Ask them if they have a copy.

- See if they ever wrote in a journal or own a journal written by someone else in the family

- Ask to see the family baby books as many families have their full trees written inside

- Ask about the photographs. Take the time to sort and organize their old photographs. Put names on the backs with a soft pencil. A box of family photographs from 50 years ago is worthless without the family history attached.

- What types of foods were cooked and served in the home when they were young? Do they know the origin of these foods? Do they have a family cookbook you can see and copy? Women used the cookbooks as a place to jot down memories for themselves. A lot of history comes from those notes

- Ask them if they have a box with old letters and papers that you can see

- What holidays did the family typically celebrate?

Unless your family has spoken openly about having Jewish lineage, it is highly advisable that you ask for information about a possible link to a Jewish past at the very end of all the questions. The secret of Jewish lineage is still heavily guarded today in many Hispanic families, and you want to gather as much information as possible before hitting any kind of brick wall.

After you get all the factual genealogy information from your relatives, make sure you write it down immediately and go over with them any questions that you might have. You may have to ask an elderly person a few times about the names or places, as their memories begin to wane. You want to be certain that you have it all down accurately. Keep a register of who gave you what information so that later you can validate some of these findings.

Ask some questions about heritage and customs. These interviews should not go on for more than an hour. If you find that they do, then you should schedule another time so that the information will be accurate. Below is a list of customs that will be indicators of a Sephardic lineage. In and of themselves, these traditions do not indicate a true Jewish identity, but you are building up a case for your own lineage. All the information will be helpful and will give you a background of the family and a lot of possible circumstantial evidence.

Crypto-Jewish families share many customs such as cousin intermarriage in every generation, many priests and nuns in the family ,unusual cooking customs or rituals , washing hands before meals, not trusting anyone, historically working in typical Jewish fields such as silversmiths, jewelers or cloth dealers, family members never entering a Church, eating special meals on Friday nights, lighting two candles on Friday nights, fasting on a random day that is not a Catholic holiday, shawl placed over the shoulders of a couple being married in a Church, sweeping to the center of the room, venerating icons but not statues only and many more.

There were also cooking customs such as looking for blood in the eggs and meticulously checking vegetables for insects or throwing dough into a fire after baking large amounts of dough, not mixing meat and milk because it would make you ill and many more.

Death rituals such as covering mirrors when someone dies or burying the dead within 24 hours are customs that were maintained for centuries. Other similar customs such as hair and nail clippings not thrown away but burned or kept in a safe place. Other customs include changing the name of a person who is ill, a strong belief that the family descends from royalty, not working Saturdays as well as children not being baptized.

Make sure you interview everyone. Call or write to them by e-mail or letters if they are not in the same city or country. Try to cover all of your relatives. Continue to record all the information. You will be able to know if you have the circumstantial evidence that your family was Jewish after you finish these long interviews. Do not despair if you do not have this information or if nothing was kept. Remember, many conversions took place in 1391, and more than 620 years have passed. You could still have a Jewish lineage even though the customs did not survive.

Looking towards other countries and sources to compile a full history

Many will have ancestors that settled in other countries around the world, and in some of those countries it may be possible to find some clues on the headstones.

In Mexico, for example, there are still headstones that will have the Catholic cross and a Jewish symbol also present such as a shin, a chai, a Star of David, or even a small menorah.

In many Caribbean Islands such as Jamaica, Barbados, Curacao, and others, you can still find cemeteries of the original Jewish settlers. Their headstones are not only clearly visible but records were kept.

In Jamaica, for example, there has been for years a contingent of volunteers that have dug up these stones and digitized the information.

Looking deeper into the Crypto-Jewish surnames

It helps to look for all the references to the names you find as being Jewish. There are many country websites that you can look at, and the more references that you find for each name, the more certainty you have that the name was used as a Converso Jewish one. but you will still have to go back a long way to actually prove it and see if the name was in your family during the times of the Inquisition.

A name alone is not enough proof. Names were bought and sold and taken on at a whim, they were picked out of the blue and even given by a priest. The reason I am adding this step to research the name fully via the internet is so that you build a case of circumstantial evidence that will accompany your genealogical search with all the full primary sources. With every grandmother you find, you will find a new last name to research.

Assuming your last name is Ramos, for example, you then will want to do internet searches for the names by searching with the following possibilities using the last name Ramos as an example:

- Ramos Judio Converso

- Ramos nombre Judio

- Ramos Converso Jew

- Ramos Jewish name

- Ramos Spanish Inquisition

- Ramos Inquisicion

- Ramos nombre Marrano

- Ramos Marrano name

- Ramos nom Juif

- Ramos Crypto-Jewish name

- Ramos nome Judaico

- Ramos Heraldica

- Ramos Heraldry

- Ramos famosos

- Origenes de la familia Ramos

- Origins of the Ramos Family

- Origens Da Familia Ramos

The more searches in different languages that you make, the more information you will be able to gather. Once you get results in each and every category above, you should not just read the first three or four hits on your search engine. You really need to go all the way through each result. The more obscure results are usually the richest with information. Use many search engines because many times, they will yield very different information.

You will notice that at this time, the focus is only on the last names. If you do your search in this way, you will eventually find some common ground in the city of origin of your ancestors. This will be very very helpful if you do not know where they are from originally. The results should point you to a region of the Iberian Peninsula at best. When you start to see, for example, that the name Ramos was usually used in the Spanish city of Zamora, then it is important to start documenting the Jewish population of the city as well. You are building circumstantial evidence.

Those searches should look something like this:

- Ramos + Zamora

- Ramos + Spain

- Ramos + Zamora + Spain

- Ramos + Zamora + España

- Jewish Zamora

- Judíos Zamora

- Judíos Conversos en Zamora

- Historia Judia de Zamora

- Jewish history of Zamora, and more.

This should yield a rich insight into the villages where your ancestors lived. You will learn much about your family history while trying to find the Jewish connections to your names.

Always have near you a map of Spain and Portugal that shows the areas clearly marked with the words Aragon, Castilla, etc. This will help when trying to find the area of family origin. Note that contrary to what most people think, in the late 1400s and early 1500s, people were moving around a lot and going from place to place. They did not sit still.

There is also a major challenge in looking up Converso names for one or more of the following reasons, so keep these in mind as you search so that you follow the correct family back. This is why primary sources are crucial.

The challenge of Converso names

- Name changes took place in the Iberian Peninsula as a way of insulating families from the Inquisition

- A family would take on or buy an old Christian family name

- A priest sometimes gave a person a last name that was randomly selected when he converted and baptized them

- Names were sometimes chosen by the person that was converting

- Names were made up during that time period, utilizing names of objects like Cuchillo for knife or the names of flowers or trees such as Lavanda or Pinos. Names of animals, bridges, and even villages were used.

- Having a typically Converso Jewish surname today is not enough to claim ancestry. A lot has happened in the last 500 years.

- It is easier to trace a surname from a paternal lineage. Many have survived the centuries, but most people are looking for their maternal lineage, where the surname usually changes with each generation.

- The surname was sometimes taken from the mother and at other times from the father and sometimes a grandparent or another relative. Therefore, if Maria Ramos and Jose Ramires would have a boy, usually his name would not be Juan Ramires. It might be Juan Ramos or even Juan Fernandez. There was neither rhyme nor reason for these changes. Many lived with several aliases used for personal or business ventures. Always ensure that you go slowly, birth certificate after birth certificate, so that you are looking only at your family and have not bumped into another family line by mistake. Inquisition processes will need to be found for family in your direct line. If you are looking for a maternal lineage, then those processes must sit squarely on your mother’s line, some 15-18 generations ago. You will need to know the villages where your family lived between 1492-1650 or so. These were the years that have a lot of documentation in the archives of the Inquisition tribunals. Each major area in Spain and Portugal was governed by a different tribunal. For example, if one lived in Sevilla, which is in the South, his or her records would be in a totally different tribunal than if they lived in Zamora in the Northwest.

Explore more about Crypto-Jewish genealogy

There are thousands upon thousands of resources available on the internet, but only the best and most interesting for gathering historical information useful to Crypto Jewish lineages will be covered here.

- Genie Milgrom - This site is free to use and has over 60,000 entries from the Inquisition Tribunals, and over 160 Books, dissertations, and many other sources. It is the most comprehensive collection available to search lineages on the internet. You will find a search engine to look for a surname but also search for a name under the anywhere because there is much genealogical data available in many fields. There are many pages with lists of all the archives available in Spain and Inquisition records from around the world.

- Sephardic Gen - This site is a great one and not because it has more historically Sephardic names than other web sites but because it houses so many specialty collections. Mostly they are data bases of Sephardic Jews that left the Peninsula but still worth a mention. It is very rich in content because it covers much more than just name information. Be careful as much more information is available since this website was created souse it as a starting point in any of the collections.

- Portal de Archivos Españoles (PARES) - This is the website for the national archives that are digitized in Spain. Please note that there is no soundex which is a program that is installed in most of the genealogy search engines where you type a word and all the results will “sound like” the word you were searching for so be cautious of this if you don’t find something right away. You must type it in a myriad of ways. While there are very old records as well as ship records and some Inquisition records, you can also find notarial records, information on land acquisitions, royal orders from the kings, heraldry, special royal instructions and in some municipalities, you can find criminal records. This is a great location to search for your family name to determine what village they may have come from. It is tedious, but if you type in the name of your family as I did for the name Ramos for example, I was able to filter the results.

Below are suggested archives in Spain that may or may not have websites:

- Archivo General de Simancas

- Contaduría Mayor de Hacienda

- Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte.

- Consejo Real de Castilla

- Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid

- Real Audiencia y Chancillería de Valladolid

- Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica

- Delegación Nacional de Servicios Documentales de la Presidencia del Gobierno

- Armero, José Mario

- Archivo Histórico Nacional

- Archivo de Luis Rosales Camacho

- Archivo de Margarita Nelken Mansberger

- Colegiata de Santa María la Mayor de Calatayud (Zaragoza).

- Delegación Provincial de Hacienda de Madrid

- Fiscalía del Tribunal Supremo

- Ministerio de Hacienda

- Colección objetos

- Cancillería. Registro del Sello de Corte.

- Colección sellos en tinta

- Archivo de Salvador Damato y Phillips

- Colección Códices y Cartularios

- Monasterio de Santa María de Melón

- Universidad Central

- Archivo General de la Administración

- Estudio Fotográfico "Alfonso"

- Ministerio de Información y Turismo

- Gobierno General de Guinea/Comisaría General de Guinea

- Sección Nobleza del Archivo Histórico Nacional

- Archivo de los Duques de Osuna

- Archivo de los Marqueses de Mendigorría

- Archivo de la Familia Ovando Archivo de los Duques de Fernán Núñez

- Archivo de los Condes de Luque

- Archivo de los Vizcondes de Altamira de Vivero

- Archivo de los Duques de Frías

- Archivo General de Indias

- Casa de la Contratació

- Patronato Real

- Ultramar

- Indiferente General

- Diversos

- Archivo de la Corona de Aragón

- Ramos de Alós

Each of these subsections has between 50 and 100 individual references to look at. The original images in many cases are scanned and digitized. Some are notarial records, others are land sales or leases, while some are documents from private family collections. You will have no shortage of information to sift through to find what you need. Laborious? Yes. Productive? Very.

Sources and blogs

Blogs are also a great source of information .Some of the best genealogy blogs can be found on genealogy websites that are for Spain alone. A blog in Spanish is called a “foro.” So you would for example, be searching for “foros apellido Ramos” which means blogs for the last name Ramos, or you would search for “foro de Zamora” in which you are looking for a blog of a particular city. There is a website www.genoom.com that has many blogs for individual last names and villages. I found many entries for my own family names there.

If you are looking for the blogs or foros of a particular village in Spain, many times you will find these on the website of the Village Council, also known as the ayuntamiento in Spanish. Those websites have blogs of people looking for each other and descendants of people from a particular village. In most of these foros you can leave a message on a message board type of display with your e-mail address, and people write you back. It is interesting to see that even after many months you will start to receive e-mails. I found cousins in Chile and Argentina in this way, and we have kept our relationships going solely through the internet.

Facebook and other social media

You can look for groups on Facebook using only the surname you need information about after joining the group, you can ask for specific information to contribute to your search. You can also search for a specific region, and if you find an active group you are in luck! For example, I am a member of the Dutch Jewish Genealogy Group on Facebook because a lot of the

Spanish and Portuguese Jews went up into the Netherlands. The group is very helpful, and the people are incredibly knowledgeable. Whenever I ask a question of the group, I get at least 10 good answers.

On Facebook, you can also search for “apellido Ramos” and get results such as Apellido Ramos cuantos somos, Mi apellido es Ramos and many more. I joined the group and have been in touch with other genealogists searching for the same thing. A search for the name of the village will also yield rich results. Joining all these groups is tedious and time consuming but will give you great results.

By now, you will probably know what village or town your family was from in Spain or Portugal, and you will need to start researching the Converso Jews from that town in much the same way you were researching the names.

It is important that you do the search on Jewish life in the village of your ancestors as eventually you might find some clues about your own family. You should be doing this in different languages and with many google searches. If you know your family was from Cordoba, Spain, for example, then these are some of the possible searches you would make:

Cordoba Judíos, Cordoba Judio Conversos, Cordoba Familia Judia, Cordoba Jewish life, Cordoba Aljama, Cordoba Juderia, Cordoba Jewish Ghetto, Cordoba Marranos, Cordoba Converso Jews, Cordoba Sinagoga, Cordoba Synagoga, Cordoba Esnoga, Cordoba Inquisicion, Cordoba Spanish Inquisition.

For most locations in Spain and Portugal, you will be able to find Jewish history that is recorded or even buried deep within PhD dissertations on the internet. You just need to search for it.

I recommend the following website that was initially compiled by Dr. Mario Saban who wrote several books on Crypto Jewish names while in Argentina:

- Tarbut Sefarad This website has a purpose of disseminating cultural information about Jewry and Jewish history in villages all over Spain. Tarbut Sefarad has appointed a representative or expert for many towns and villages. Those specialists have taken great time and pains in documenting the Jewish history of their town. You can e-mail the specialists and garner even more useful information on the Jewish background of the people from the village of your family.

This is also a painstaking process but you must prove that not only was your family Jewish, but you should also prove that they lived in a town or village that had a Jewish community. Most of the time, the internet will be full of reliable resources to that effect.

Researching in Spain and Portugal

You will eventually have to go to Spain or Portugal, or at least be in contact with the places of origin of your family, but if you have worked your way through the internet and blogs as I have mentioned, you will have been able to find information on your family.

Always document where you got the information so that you don’t have to search for it again and again. You have a lot of ground to cover so make sure you are only going forward.

If you are lucky, you should have been able to travel back to the early 1800s or the late 1700s, and this is where your search will start to become harder. You should already have been able to document perhaps four or five generations of grandmothers and great-grandmothers and all the Jewish references to the names. This is a very painstaking process and you must have a lot of patience to see it through. Do not become discouraged. Day by day, more resources are available on the internet, as records are being digitized and put on the internet all the time.

By now, you should have been able to collect information that you have meticulously been putting in the folders of the direct lineage that you are following. Always keep in mind that your objective is to find Jewish roots from pre-Spanish Inquisition times. You are not trying to just make a family tree. The interesting thing with this search is that you will have a family tree at the end, but that is not your goal. You are collecting the data and documents to prove this lineage. There are many who do not believe that this search is possible. There are many that appear on blogs and say that this is all hype. Those people have not met me and a few others like me. We have all these documents, and it is possible. Stay on task and be patient.

When you have exhausted all the internet searches that relate to the genealogy of the family, it will be time to head to the physical records of Spain or Portugal. It is important to note at this time that you will be looking for any and all records from the village of your family relating to the line you are studying. You will be able to locate records in the Catholic churches that date back to 1545.

All of these records will look identical no matter what village or city you are looking into. In 1545, the Council of Trent convened and ordered all the churches to record the baptisms, marriages, and deaths in exactly the same way. The good news is that via these records you will be able to see your relative, the name of the parents, grandparents and the name of the witnesses, as well as the name of the scribe who wrote the information in the book. In those days scribes were used for all official documents. It is important to not only document the next generation of family but also the names of the witnesses and the scribe. This information will be useful later as many specific scribes and witnesses were found to have been judged in the Inquisition for hiding Jewish marriages and passing them off as Catholic ones.

Speaking of Catholic, if you are now in the 1700s you may start to find priests and nuns in your family tree. This is very good news which supports the many pieces of circumstantial evidence that you will start to collect if your lineage is truly a Jewish Converso one. Many times, there will be a priest in each generation or in every other generation. The Converso families needed someone that would be present at all the Catholic rituals and make sure that to the best of their ability, some Jewish rites would be observed secretly and that the Catholic ones would not be kept fully.

You will need to start contacting the city councils or ayuntamientos in the city or village that you are searching in. I would suggest that your first contact be a phone call, and once you establish a contact, you can begin to communicate via e-mail. It is possible that they still have the records you want, and they will charge a nominal fee for copying them and mailing them to you. If they are more technologically oriented then they will scan and e-mail them. Many of these archivists will not e-mail them, and they will not accept credit cards. This is a very lengthy process, but you can usually get one or two records at a time. Most of the time, they will only go back 100 years and then the records are sent to the municipal archives of the largest and closest city. In that case you will have to go in person or hire a professional genealogist who is used to working in these archives to obtain the records for you.

The older the records, the harder the Spanish is to read. Be sure that you have a working knowledge of the old Spanish before you get into the field work. You do not want to waste precious time trying to decipher documents if you are overseas and with limited time. I mentioned a website earlier in the internet references that will teach you the basics of reading medieval documents.

In the larger cities such as Madrid, you can obtain census records that are very detailed. Those census records will show you in detail who lived in the house with your relative, where each person was born and what they did for a living.

You should have been able to follow along back on your tree by now, and you may even have had to jump from city to city to follow the lineage to its origin. At each and every turn you should continue to document the last names as being Jewish Converso ones. Every time you find a new name, you must do the internet searches for the Jewish connection. This is important as you should now be in the early 1600s or late 1500s. The records become harder to read and sometimes pages are ripped out. If that happens, you may have to find a brother or a sister of the relative to continue back.

Slowly, slowly and with patience you will be able to find your way back.

Explore more about Crypto-Jewish genealogy

- How to Find Out if Your Ancestors Were Conversos, article by Daniella Levy on the MyHeritage Knowledge Base

- Spanish records on MyHeritage

- Portuguese records on MyHeritage