Christening records, also generally known as baptismal records, are church records which were produced at the time of the baptizing and christening of a child. It was only in the middle of the nineteenth century that governments in Europe and the Americas began introducing the concept of civil registration, whereby a secular record of the birth of each child in the country was made. Accordingly, for genealogists and family historians tracing ancestors back beyond the era of civil registrations and censuses, christening or baptismal records are often the best means of determining a person’s place and approximate date of birth. It was common practice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to baptize every child within a few days of their birth, sometimes even on the day they were born. It was unusual for a child not to be baptized within the first two weeks. Consequently, baptismal records give a very good idea of when a child was born.[1]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

History of christening records

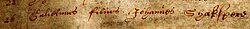

Christening records first began to appear in several European countries in the late medieval period, a by-product of the growing concern for administration and record-keeping in Europe at the time. These formed part of wider parish registers of records of baptisms, marriages, funerals and other sacramental events. The oldest extant parish registers survive in fragmentary form for some localities in Italy, France, Germany and England in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. However, it is only really from the sixteenth century that parish registers were systematically kept and have survived from, providing us with detailed christening records therefrom.[2] Typically these earlier christening records will be in Latin and so someone like William Shakespeare will be referred to as Gulielmus, the Latin for William.[3]

Christening records became a staple of most European countries by the seventeenth century. They are of immense use for genealogists where they have survived down to the present day. The reason for this is very straight-forward. While we are used today to people being recorded by the state as soon as they are born and issued with a birth certificate, this was not the case in early modern Europe, where births occurred at home. In many countries it was well into the nineteenth century before a large number of countries began requiring civil registration of births and other events like marriages and deaths, and for most others it was the first half of the twentieth century. This did not become law in England and Wales until 1837; in Sweden until 1860; in Ireland until 1864; in most of Italy until 1866; in the German Empire until 1874; in Russia until 1917; and, quite incredibly, not until 1938 in Austria.[4]

While censuses might often provide an alternative source of information of a person’s birth for genealogists, in many countries censuses were also not introduced until well into the nineteenth century or in some instances the records of early censuses have been lost during fires, wars or neglect. The result of all of this is that christening records can often be the best source available for acquiring the approximate date of the birth of ancestors born in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and indeed for much of the nineteenth century too depending on the jurisdiction.

Where to find christening records

Where one will find christening records depends on where the ancestor or person they are seeking information concerning lived. For instance, the Church of England has acted as a national church in England since the sixteenth century. This fact, along with systematic national management of the relevant records by British governments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, has ensured that church records have been archived in a uniform manner across England and Wales. The parish registers, which christening records formed part of in the early modern era, are generally found in the county records offices that are in each shire or county of England and Wales.[5]

The opposite scenario is found in the United States. The early history of the country involved it being a haven for religious dissenters and radicals from Europe and there is no national church to speak of. Therefore, church records such as those for baptisms/christenings are generally held by local churches. Depending on the specific arrangements within individual cities, towns and localities, agreements might have been reached whereby individual local churches or congregations have deposited their older records with local libraries and archives in order to make them more generally accessible to the public.[6] Each scenario is different and has evolved owing to local and national considerations and historical circumstances. A wide range of christening records are available through MyHeritage, including a vast series of 192 million birth and christening records for England between 1538 and 1975.

What can be found in christening records

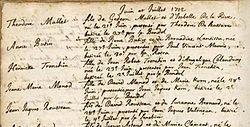

Christening records can often be quite basic in terms of the information they contain. Nevertheless, where they are available in lieu of census records or other demographic records, they are of great use to genealogists, family historians and anyone tracing their ancestry. At a minimum the name of the individual being baptized and the date of the christening will be provided. As noted earlier, baptisms in centuries gone by were nearly always performed within days of the child being born and sometimes just hours afterwards. Therefore the date of birth of an ancestor can be extrapolated to within 1-14 days with a fair degree of certainty from the date of baptism. This is especially the case for the sixteenth, seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Towards the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth the length of time between birth and baptism began to grow larger.[7]

Additional details that may or may not be provided depending on a range of factors are information concerning the parents of the infant being baptized and the godparents. Further information, such as the religion of the parents and the address can necessarily be derived from where the christening records are located. For instance, if the christening record being considered is found amongst the parish registers for the Church of Ireland in a village in Lancashire, then it can reasonably be deduced that the family lived in or near that village and the parents adhered to one extent or another to Anglicanism.[8]

See also

Explore more about christening records

- England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975 records collection on MyHeritage

- Hungary Reformed Church Christenings, 1624-1895 records collection on MyHeritage

- United States Births and Christenings, 1867-1931 records collection on MyHeritage

- Mexican Catholic Parish Records, Part I: Baptisms, Confirmations & Burials at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Christening: Welcoming a new baby at the MyHeritage blog

References

- ↑ E. A. Wrigley, ‘Births and Baptisms: The Use of Anglican Baptism Registers as a Source of Information about the Numbers of Births in England before the Beginning of Civil Registration’, in Population Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (July, 1977), pp. 281–312.

- ↑ M. H. Skolnick, L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, A. Moroni, E. Siri and L. Soliani, ‘A Reconstruction of Historical Persons from the Parish Registers of Parma Valley, Italy’, in Genus, Vol. 29, No. 3/4 (1973), pp. 103–155.

- ↑ https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/blogs/birth-and-burial-records-william-shakespeare/

- ↑ Christopher Pollitt, ‘Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Identities’, in Christopher Pollitt, New Perspectives on Public Services: Place and Technology (Oxford, 2012), pp. 159–171.

- ↑ https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/birth-marriage-death-england-and-wales/

- ↑ https://archives.boston.gov/repositories/2/resources/857

- ↑ B. Midi Berry and R. S. Schofield, ‘Age at Baptism in Pre-Industrial England’, in Population Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Nov., 1971), pp. 453–463.

- ↑ https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/about-us/our-faith/historical-records