Brazilian ethnicity comprises a combination of indigenous and European origins, primarily due to European colonization of the Americas from the sixteenth century onwards. When the Portuguese first began settling in the coastal regions of the north and east of the country, Brazil was inhabited by millions of native Amerindian people.

However, over the next two centuries, war and, more significantly, the introduction of European diseases decimated the indigenous peoples. This process continued through to the twentieth century as the Amazonian rainforest was penetrated more and more.

While the Amerindian population has been dramatically reduced in early modern and modern times, the country was settled extensively by both Europeans who arrived voluntarily and millions of slaves transported across the Atlantic between the mid-sixteenth century and the late nineteenth century.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Brazilian history

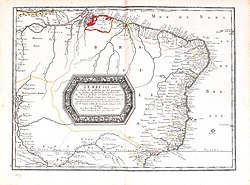

The vast region which constitutes Brazil today was not a homogenous political entity in pre-colonial times, but was a large tapestry of regions inhabited by hundreds of different Amerindian tribes, some of which had been dominant in their respective regions as far back as 8000 BCE. While there was a certain degree of development here in pre-colonial times, such as pottery being produced here as early as the sixth millennium BCE, there is a lack of overt historical information available for the eastern regions of South America. This is unlike Central America, where the cultures of the Olmecs, Mayans, Aztecs, and others are well-documented. Brazil was virtually unknown to Europeans when the Treaty of Tordesillas, agreed between Spain, Portugal and the Papacy in 1494, accidentally gifted it to the Portuguese.[1] As the Portuguese discovered the extent of their new territory in the sixteenth century, they began establishing a range of coastal settlements in the north and east, primarily to exploit the country’s brazil-wood trees for its valuable red dye.[2]

It wasn’t long before a combination of European diseases such as measles and smallpox devastated the population of the Amerindian peoples living nearest to the sites of Portuguese settlement. Consequently, the Portuguese pioneered the mass transport of slaves from western Africa across the Atlantic to their American colonies. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Portuguese imported over four million slaves into Brazil. This was approximately seven times the number imported into the Thirteen Colonies and subsequent United States during the same time period. In the process, the demographics of Brazil were changed enormously in ways that still resonate in the make-up of Brazilian society today.[3]

Brazil remained a Portuguese colony down to the nineteenth century, though it was briefly challenged by the Dutch in the region in the first half of the seventeenth century. The Portuguese royal family went into exile in Brazil during the Napoleonic Wars of the early nineteenth century, following which Brazil was made a separate kingdom in 1815. An Empire of Brazil followed, one which was incredibly retrograde by Western standards in not abolishing slavery until 1888, the last Western nation to do so. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the extensive settlement of the vast South American nation by migrants from countries like Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Spain. However, like other nations of Latin America which prospered in the first quarter of the twentieth century, Brazil suffered following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression, falling into military juntas, political repression, and economic stagnation for much of the remainder of the twentieth century. Today Brazil is still a divided country as the twin forces of a desire for economic expansion clash with the need to preserve the vast Amazonian rainforest.

On 13 May 1888, Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, passed the ‘Golden Law’ (Lei Áurea) as regent of Brazil, which finally banned slavery in Brazil, making it the last Western nation to do so.

Brazilian culture

In large part owing to its diverse demographic makeup Brazil has emerged as a country with a varied culture, which blends elements of Iberian and West African traditions. The most ubiquitous and distinctly Brazilian element of this is the focus on celebrating Carnival. Cities like Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo have the largest festivals to celebrate this springtime holiday. This fuses elements of Brazil’s dance and music culture and its affinity for beaches and colorful dress. While Carnival is a festivity of European origin, much of the pageantry, dance, music, and color associated with it in Brazil comes from West African cultural traditions.[4]

Beyond this Brazil is possibly most famous culturally for its position as the world’s foremost footballing nation, having won the FIFA World Cup a record five times, in 1958, 1962, 1970, 1994, and 2002. Pele, its recently deceased greatest footballer, was a national hero, while the Canary Yellow color of the nation’s football jerseys has become the national emblem. Yet, during the recent FIFA World Cup in 2022, this became politically divisive in a country with myriad social, political, and economic divisions. These are often based on ethnic descent and the better income and life opportunities available to people of a strictly white heritage than mixed ethnicity or African.[5]

Brazilian languages

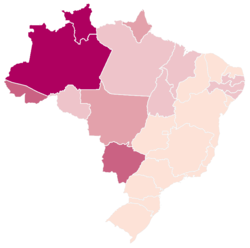

In line with its modern colonial history, Portuguese is the national language of Brazil and the most widely spoken tongue across most of the country. However, there are still a significant number of indigenous languages spoken here. Studies suggest that when the Treaty of Tordesillas bequeathed Brazil to Portugal in the final years of the fifteenth century there were over 1,300 different native languages spoken across the vast country by millions of Amerindian people. While this has declined dramatically, there are still approximately 200 native languages spoken here, such as Apalai only used by a few hundred people, while others, such as Nheengatu and Tucano, which have thousands of native speakers. Because of Brazil’s location within a continent which was otherwise colonized almost entirely by the Spanish in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Spanish is also spoken widely in some parts of Brazil, notably along the southern regions bordering Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina.

Arrivals from other European communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay became major centers of European settlement, brought their own languages with them. Many of these have survived in some limited form down to the present day. An example is Hunsrik, a dialect of German that originated in the Franconian region of west-central Germany. This mismatch of languages has ensured that Brazilian Portuguese differs somewhat from European Portuguese and there are borrowings from the indigenous languages and other European tongues within the form of Portuguese spoken across Brazil today. English remains comparatively under-spoken by comparison with other Latin American nations, and visitors to Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo will still find many places with few English speakers.[6]

Explore more about Brazilian ethnicity

- Explore the most common ethnicities in Brazil on MyHeritage

- Indigenous Amazonian ethnicity on MyHeritage

- Brazilian historical record collections on MyHeritage

- Brazilian Football Legends Discover Their Roots With MyHeritage DNA on the MyHeritage Blog

References

- ↑ https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/treaty-tordesillas/

- ↑ https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/fodors/top/features/travel/destinations/centralandsouthamerica/brazil/riodejaneiro/fdrs_feat_129_9.html?pagewanted=1

- ↑ https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/slavery-brazil

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/place/Brazil/Cultural-life

- ↑ https://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/research-projects/politics-and-sport-in-latin-america/brazil/

- ↑ https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/most-spoken-languages-in-brazil