The first birth records in Ireland were registered after the approval of the Registration of Births and Deaths (Ireland) Act 1863, which allowed for the appointment of a Registrar General in Ireland and the setting up of a General Register Office in Dublin. The civil registration of births, deaths and Roman Catholic marriages in Ireland commenced on 01 January 1864 and non-Roman Catholic marriages had been subject to civil registration since 01 April 1845. In comparison, civil registration had been introduced to England and Wales on 01 July 1837 and to Scotland on 01 January 1855.

In Ireland, the Poor Law system which saw the establishment of Poor Law Unions, a local government unit in the UK and Ireland,[1] as back as in 1838. The Poor Law Unions usually centered on market towns were based on groupings of townlands; townlands and Poor Law Unions can straddle parish and county lines. The Poor Law Unions were divided into Dispensary Districts with up to seven Districts in each Union. For the purposes of civil registration, the Superintendents Districts were based on the Poor Law Unions and each of the Superintendents Districts were sub-divided into smaller Registration Districts based upon the Dispensary Districts. As the Poor Law Unions and Superintendent Registration Districts can straddle county boundaries, it can create some confusion when searching for records. The Poor Law Guardians were tasked with establishing a Register Office in each Poor Law Union. A map of Ireland’s Poor Law Unions may be found here. The Clerk of the Poor Law Unions could be appointed as the Superintendent Registrar while the Medical Officers of Dispensary Districts could be appointed as the District Registrars.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Contents of Birth records in Ireland

Date and place of birth

When civil registration was introduced in Ireland, notice of the birth had to be provided within twenty-one days and the birth had to be registered within three months. However and as expected, late registrations occurred and also, some births failed to be registered. In the early years of civil registration, it was not unusual to see baptisms of children occurring supposedly before the child was born. In order to avoid prosecution or a fee (2 shillings and six pence) for late registration, parents would often alter the date of birth of the child when registering it, which explains how a baptism could occur before the birth. Consequently, birth registrations have to be taken with a liberal dose of salt. After the Births and Deaths Registration Act was passed in 1874, the time for registering a birth was reduced to 42 days.

One interesting example of late registration is the one of the siblings Daniel and Alexander Nelson. Daniel's birth on 09 December 1864 at Ram’s Island, Glenavy, County Antrim was registered on 04 January 1865 at Crumlin, County Antrim by Sarah Mulholland, who was present at the birth. Daniel’s father was Alexander Nelson, a fisherman and caretaker from Ram’s Island and his mother was Eliza Nelson, née Fitzgerald. Alexander Nelson, on the other side, was born on 10 December 1864 at Ram’s Island, Glenavy, County Antrim. His birth was registered on 22 December 1864 at Glenavy, Lisburn, County Antrim by the father, Alexander Nelson, a labourer of the same address. His mother was Eliza Eliza Nelson, née Fitzgerald; clearly, these boys are not twins, otherwise their births would have been registered at the same place on the same day by the same person. It is also clear that they have the same parents and that they are brothers. The conclusion is that the parents decided to register the births in different registration districts to avoid suspicion and that the birth registration of at least one of the children was late. In the case of twins however, we usually see the time of each birth of each child recorded.

Often, first-time mothers returned to the home of their mother to give birth and in these cases the place of birth can be different to the residence of the father. In the example provided here, entry number 228 shows that Rose Ann Burns was born in the townland of Crusheybracken, in the parish of Rasharkin, County Antrim and her father was living at the same townland. This is really valuable information because it ties the family to a specific townland and knowing this can help to differentiate between different Burns families.

Name of the child

The forename of the child had not always been decided upon at the time of the registration, which can make searching for a birth problematic. If you are experiencing difficulties, simply leave the forename blank on the online search form. The final column allowed for the baptismal name to be entered at a later date. As this was subject to an additional fee of one shilling, it was rarely completed. The spelling of names was often inconsistent and the surname could be spelled different ways on the same registration record. If the person providing the registration information was illiterate they would be none the wiser as to the spelling that was at the whim of the Registrar. The Mac and O prefixes could be dropped and adopted again at a later date.

Name, surname and dwelling place of the father

In some cases, the father was away working in another area or country and this can be an explanation for a different address to the place of birth. Until The Births and Deaths Registration Act 1874, the father’s name of an illegitimate child could be entered on the birth registration. The 1874 Act required that the name of the father was only to be entered at the joint request of the mother and the father and that both the father and mother should sign the register. In the case of illegitimate children where no father’s name has been entered in the register, there are often clues in the forenames column. A child may be given the father’s surname as a middle name or indeed be given the full name of the father as forenames and middle names. Officially, an illegitimate child was given the surname of the mother but in later life, illegitimate children often adopted the surname of their father without any official documentation to record this change, which of course can make it difficult to track them down.

Name, surname and maiden name of the mother

The maiden name of the mother provides useful information to enable a search for a marriage record for the couple.

Rank or profession of the father

The rank or profession of the father was recorded and from a social history perspective, it is interesting to trace the movement of labourers, weavers and small farmers away from the land towards the burgeoning industrial centres. In the case of the gentry, we often simply see ‘gentleman’ entered under this column.

The signature, qualification and residence of the informant

The person who registered the birth could be the father, mother, nurse or a person present at the birth. In the case of the death or inability of the parents to register the birth, the occupier of the house or tenement in which the child was born could complete the registration as well. In mid to late-nineteenth century Ireland, most births still occurred at home, usually without a doctor. However, local midwives or other female family members such as grandmothers and sisters assisted and if they were present, they could register the birth. In one example of an unqualified informant, the birth registration of Alexander Hill was completed by his grandfather on 06 November 1883 in Larne, County Antrim. On 29 July 1884, this registration was cancelled by the Registrar because the qualification of the informant was illegal and a new birth registration was issued with Alexander’s mother as the informant. The informant was to sign their name and this is where we quite often see a cross inserted instead of a signature, which signals that the informant was unable to write. The example here shows that Rose Ann’s father William John Burns of Crushybracken registered the birth and made his mark rather than signing his name. It is worthwhile taking note of the name and address of the informant as they were often relatives - this can help to expand the family tree and help to determine townlands of residence for wider family members, particularly in rural areas.

Marine Register Book of births

For any child of an Irish parent born at sea on board a British vessel, the Captain or Commanding Officer was to make a minute in the ship’s log with sufficient information required to register the birth of the child, including its name and the name of the vessel in which the birth took place. Upon arrival in any port of the United Kingdom, a certified copy of the minute was to be sent to the Registrar General in Dublin, who was to record the information in the Marine Register Book of Births.

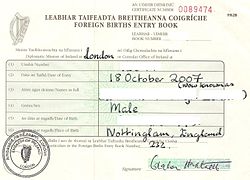

Foreign Register of births

The Foreign Births Register allows the descendants of Irish people who have moved abroad to register as Irish citizens.[2] The birth of any child of Irish parents in any foreign country, could be registered in The Foreign Register by the Registrar General. Information had to be supplied within twelve months and to be certified by the British Consul of the country or district in which the birth took place.

Army records

The Registration of Births, Deaths, and Marriages (Army) Act, 1879 stipulated that officers or soldiers who were Irish subjects and their families had birth, marriages and deaths registered and the information transmitted to the Registrar General of Births and Deaths in England who was to forward the information to the Registrar General in Ireland.

Stillbirths register

All stillbirths occurring in the Republic of Ireland since 1 January 1995 may be registered, but it is not obligatory. Registration of a stillbirth only applies in relation to a child born weighing not less than 500 grams or having a gestational age of not less than 24 weeks and who shows no sign of life at birth. The Registration of Still-births (Northern Ireland) Act 1960 made it a requirement to register all stillbirths in Northern Ireland. The register dates from 01 January 1961 and it is not open for public search.

Adopted Children registers

Compilation of registers and indexes

The 1863 Act[5] stipulated that each January, April, July and October, every District Registrar was to make a certified copy of each marriage, birth and death and forward it to the Superintendent Registrar. When each Register book was complete, it was to be sent to the Superintendent Registrar. Four times per year, the Superintendent Registrar was to send the copies to the Registrar General in Dublin. Indexes were to be compiled in each Superintendent Registrar’s office and also in the Registrar General’s office – these were to be open for searching by the general public and certified copies of entries were to be made available upon payment of a fee. Between 1864-1877, the indexes are annual, arranged alphabetically by family names. From 1878 onwards, the indexes are quarterly (4 per year). The information in the birth indexes contains details such as name of the child, district of registration, year and quarter of registration, volume number and page number. From 1900, the birth indexes also include the mother’s maiden name.

Where to find civil Birth records in Ireland

General Register Offices

In 1921, Ireland was partitioned – the six counties of Antrim, Armagh, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Down and Londonderry became Northern Ireland and remained part of the United Kingdom. Following partition, a new General Register Office was established in Belfast to manage registrations in Northern Ireland. The remaining twenty-six counties became the Irish Free State - at different times it has also been known as Eire, the Republic of Ireland or simply Ireland. Having two different jurisdictions affects where you can find the civil registration records. If you are searching online, the Irish Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media has made historic copies of [www.irishgenealogy.ie birth, marriage and death records for all of Ireland up to 1921] freely available. After 1921, only the records for the twenty-six counties of the Republic of Ireland are available on that website. For the six counties of Northern Ireland, records may be found on the General Register of Northern Ireland (GRONI) website at and they go back to when registration commenced. Note that the records on GRONI’s website are not freely available. To search, you an account is required as well as and having at least one credit (50 pence) in your account. While it is free to search, there is a cost to view the records. The enhanced view costs one credit and it will provide limited information, while viewing the full record costs 5 credits (£2.50). GRONI has restrictions on downloading, copying or taking screenshots of their records; Irish Genealogy does not. The records available on these websites are historic and both have the same restrictions in terms of how recent the available online records are. You can view online:

- Births more than 100 years old

- Marriages more than 75 years old

- Deaths more than 50 years old

There are updates done to the GRONI website on a weekly basis by uploading records that fall within the above time scales, while Irish Genealogy seems to upload new records on an annual basis. Both websites provide the opportunity to purchase a copy of a particular certificate and you can also order by post.

Visting the Registrar's office

It is possible to visit the General Register Offices in person but do check with them if there are any restrictions on opening hours and if you need to book an appointment. GRONI has terminals available at the Public Records Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) located at 2 Titanic Boulevard, Titanic Quarter, Belfast BT3 9HQ. Before visiting PRONI in person, please see their website for more information about registration as a visitor; note that PRONI itself does not offer a certificate ordering service. GRONI is located at Colby House, Stranmillis Court, Belfast BT9 5RR and their website has information about the procedure for booking an appointment. Visiting GRONI in person or using PRONI’S terminals will allow for searches of records that are not subject to the historic records restrictions mentioned above.

Ireland’s General Register Office is now located at Government Offices, Convent Road, Roscommon, F42 VX53. There is also a family research facility located at Werburgh Street, Dublin 8, D08 E277 and further information about it may be found on their website. There are twenty five civil registration offices in Ireland – further details may be found here. For some of these offices you can visit and order certificates, but check the website to see what services they offer.

The availability of online Irish civil registration records has transformed family history research and the provision of free to access records on the Irish Genealogy website is a terrific boon. Do however be aware that differences in spelling, poor transcription and indexing of records and the failure to register births can hamper your search efforts. Think laterally, use different spelling variations, don’t get too hung up on dates and good luck with your research.

Explore more about Birth records in Ireland

References

- ↑ Poor Law Union Maps. Timeline Research Ireland

- ↑ The Foreign Births Register. Citizens Information Board

- ↑ 619 History of adoption in UK. BMJ Journals

- ↑ Overview of Irish Adoption Law. Center for Adoption Policy

- ↑ Registration of Marriages (Ireland) Act, 1863. Electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB)