Angel Island Immigration Station (1910–1940) offers a rich but complex trove of records for family historians. Often called the “Ellis Island of the West,” this station processed hundreds of thousands of immigrants from a diverse array of countries. Unlocking these records can provide invaluable details about ancestors – from transcripts of interrogations and health inspections to photographs and personal documents – but it requires understanding the history, knowing where to find the files, and learning how to interpret the information. This article will walk through Angel Island’s historical context, the immigrant groups who passed through, the types of records created, and a step-by-step approach to locating and using Angel Island immigration records in genealogical research.

Historical Overview of Angel Island (1910–1940)Historical Overview of Angel Island (1910–1940)

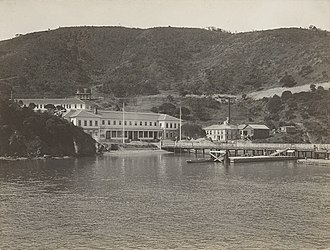

Angel Island Immigration Station, located in San Francisco Bay, operated from January 21, 1910, until November 1940 as the primary West Coast immigration facility. It was established largely to enforce restrictive immigration laws (most notably the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882) and to control the flow of immigrants from Asia. Unlike Ellis Island – which mostly processed European immigrants in a matter of hours – Angel Island often detained and interrogated immigrants for days, weeks, or even months. The station’s isolated location and barrack-style detention facilities were deliberately designed for prolonged confinement and scrutiny.

Volume and Diversity of ImmigrantsVolume and Diversity of Immigrants

Between 1910 and 1940, estimates suggest that half a million to one million immigrants were processed at Angel Island. These arrivals came from over 80 countries around the globe. The majority were from Asian nations – especially China and Japan – but many others came from Europe, Latin America, and the Pacific islands. In fact, roughly 250,000 Chinese and 150,000 Japanese immigrants passed through Angel Island during its 30 years of operation. Smaller yet significant numbers of immigrants arrived from Korea, British India, the Philippines, Russia, Mexico, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and other regions. Immigrants whose paperwork was in order were often allowed to disembark directly in San Francisco, but anyone requiring further inspection (due to immigration quotas, exclusion laws, or health concerns) was ferried to Angel Island for processing.

Detention and InterrogationDetention and Interrogation

At Angel Island, immigrants faced medical examinations and detailed legal interviews. About 75–82% of arrivals were ultimately admitted to the U.S., a far lower acceptance rate than at Ellis Island. Those suspected of violating exclusion laws or deemed likely to become public charges underwent intense questioning by the Immigration Service’s Board of Special Inquiry. Chinese immigrants in particular endured lengthy interrogations about minute details of their family and village to prove they were eligible to enter (for example, as children of U.S. citizens or merchants). The detention facilities were crowded and unpleasant, and many detainees expressed their frustration by carving poems into the barrack walls, some of which are still visible today as a poignant reminder of their experience.

Closure and LegacyClosure and Legacy

In August 1940, a fire destroyed the Angel Island administration building, and immigration processing was moved to mainland San Francisco. A few years later, in 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed (though strict quotas remained in place until 1965). During World War II, the station was repurposed to detain Japanese immigrants and others considered “enemy aliens.” The Angel Island Immigration Station’s legacy is a complex one – it served as a gateway for thousands of newcomers, but also as a site of hardship and discrimination. The records created through its operations now reside in archives, offering detailed snapshots of immigrant lives and trials.

Angel Island Immigration RecordsAngel Island Immigration Records

Over its three decades, Angel Island generated a wealth of documentation on incoming (and outgoing) travelers. For every immigrant subject to inspection, officials created case files containing interrogations, affidavits, and identity papers. Passenger manifests recorded all arrivals by ship, and “held for special inquiry” lists noted those detained for further review. Medical officers kept logs of health exams and quarantine holdovers. Photographers took identification mugshots of many detainees. Because of the investigative nature of the station, the National Archives at San Francisco (NARA) today holds an enormous collection of these files – more than 200,000 immigration investigative case files, often referred to as “Chinese Exclusion Act case files” or Angel Island case files, spanning the 1880s through the 1940s. These records are a treasure trove for genealogists, preserving personal details that may not exist anywhere else.

Immigrant Groups Processed at Angel IslandImmigrant Groups Processed at Angel Island

Angel Island processed immigrants from a wide variety of ethnic and national backgrounds, each with their own immigration experiences and challenges. Below is an overview of the major groups and how their cases were handled:

Chinese ImmigrantsChinese Immigrants

Chinese immigrants were the largest group detained at Angel Island, owing to the restrictive Chinese Exclusion Act and related laws. Roughly 175,000 to 250,000 Chinese passed through the station. Chinese laborers were barred from entry under the Exclusion Act (1882), so those arriving had to fit into exempt categories (such as merchants, students, or U.S.-born children) or attempted to enter under false identities as “paper sons” or “paper daughters.” This led to rigorous interrogations: officials asked detailed questions about the immigrant’s home village, family lineage, and even minute household details to catch those using assumed identities. Case files for Chinese immigrants tend to be very rich, including verbatim interrogation transcripts, witness statements, and correspondence. Many Chinese immigrants spent weeks or months at Angel Island awaiting decisions, and about 18% were ultimately deported if officials were not satisfied with their claims. Despite the hardship, the information recorded can provide genealogists with Chinese names (sometimes in characters), ancestral village maps, and multi-generational family data. Note: Chinese detainees often used “paper names” (adopted surnames to circumvent exclusion laws), which means the surname on the Angel Island records may differ from the family’s true surname. Researchers should be aware of this and look for clues in the files that reveal the original family name or subsequent affidavits where the individual confessed their real identity in later years.

Japanese ImmigrantsJapanese Immigrants

Japanese immigrants were the second-largest group on Angel Island, estimated at roughly 85,000–150,000 between 1910 and 1940. Japan was not subject to a blanket exclusion law like China; instead, the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1907 and later the Immigration Act of 1924 curtailed Japanese labor immigration. However, Japanese women and children continued to arrive, often as wives (“picture brides”) or family of male immigrants already in the U.S. Angel Island officials still detained and processed many of these arrivals for verification of their relationships and documents. Japanese immigrants generally faced shorter detention periods than Chinese immigrants if their papers were in order, but they, too, underwent interviews and medical checks. Records for Japanese arrivals may include case files if there was a legal inquiry (for example, confirming a marriage’s legitimacy), but many Japanese simply appear on passenger lists and “Special Inquiry” logs with minimal file documentation if admission was straightforward. If your Japanese ancestor came through Angel Island, look for passenger manifest entries (often noting “wife of ___” or similar) and any available INS correspondence or affidavits in NARA’s case file collections. Keep in mind that Korea was under Japanese rule during this period – Korean immigrants often traveled with Japanese passports or via Japan, but U.S. records usually identified their Korean ethnicity or origin in the “nationality” column.

Korean ImmigrantsKorean Immigrants

Korean immigration to the U.S. in the early 20th century was relatively small but noteworthy. Many Koreans came as political refugees, students, or Christians fleeing Japanese colonial rule after 1910. Others had first gone to Hawaii as laborers and then made their way to the mainland. At Angel Island, Korean arrivals were typically recorded as “Korean” in nationality (especially before 1910) or sometimes as Japanese nationals of Korean ethnicity during the colonial period. They were subject to the same immigration laws as other Asians. There was no specific exclusion act targeting Koreans, but the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917 effectively banned new immigration from most of Asia (not including Japan and the Philippines) which would have curtailed Korean entries as well. Therefore, many Korean immigrants passing through Angel Island did so before 1917 or under special circumstances (such as family of U.S. residents). Genealogically, Korean case files may contain Japanese-language documents (if they traveled under Japanese papers) as well as Korean personal names that might have various English spellings. Researchers should look for them in NARA’s case file index and passenger lists around the dates of known arrival, and be prepared to encounter Japanese terminology or paperwork in the files. While fewer in number, Korean detainees’ records can be valuable, sometimes detailing family background in Korea or connections to Korean American communities.

South Asian (Indian and Pakistani) ImmigrantsSouth Asian (Indian and Pakistani) Immigrants

Angel Island also processed immigrants from South Asia, primarily from British India (regions of today’s India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). An estimated 8,000 South Asian immigrants (often Punjabi Sikhs, as well as Muslims and Hindus from Punjab) passed through Angel Island between 1910 and 1940. Many were agricultural or mill workers who initially arrived on the West Coast seeking jobs. South Asians faced particularly harsh treatment: they had the highest rejection rate of any group at Angel Island – over half of Indian entrants from 1911 to 1915 were refused admission and deported. Racist attitudes and legal barriers (like the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917, which explicitly banned immigration from British India) severely limited their chances after 1917. Angel Island case files for South Asian immigrants often contain records of Special Inquiry hearings, where officials questioned them about their caste, region, or whether they had valid work offers, etc. Some South Asians claimed exemption as British subjects or as returning residents, and a few pursued legal appeals. For genealogists, if you have an early 20th-century Indian or Pakistani ancestor in California, do check for an Angel Island case file. These files might include personal descriptions, the person’s father’s name (useful for South Asian patronymic research), and even photographs. Note that many South Asian names were unfamiliar to American inspectors, resulting in varied spellings; search indexes with flexible spellings (for example, “Singh” might be indexed correctly, but “Kaur” could be misspelled, etc.). Also, some South Asian immigrants who were denied entry left traces in federal court records if they filed habeas corpus petitions to contest their exclusion.

Russian and Eastern European ImmigrantsRussian and Eastern European Immigrants

Angel Island’s reach extended to immigrants from the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe, especially those who traveled via Asia. Approximately 8,000 Russian immigrants came through Angel Island during the station’s operation. This group included White Russian refugees fleeing the Russian Revolution and civil war, Jewish families escaping pogroms by taking the Trans-Siberian route to Pacific ports, and other Eastern Europeans who arrived on ships from the Far East. Most European immigrants and travelers in first or second class were processed quickly – usually aboard ship or at the San Francisco dock – and not sent to Angel Island unless there was a problem. However, some Russians and other Europeans were sent to Angel Island for further inspection, especially if they arrived without proper visas after the implementation of national origin quotas in the 1920s or if they were suspected of being likely public charges. Generally, “white” European arrivals faced less stringent interrogation than Asian immigrants – their detention was often short-term pending routine paperwork. For genealogists, this means your Russian or Eastern European ancestor might show up in passenger manifests (with possibly a notation of “detained for meals” or “transferred to Angel Island”) and might have a slim case file if any. Check NARA’s indexes for Slavic-sounding names or search by date/ship in the “arrival investigation files.” Also, consider naturalization records – many Russian immigrants who came via Angel Island later naturalized, and their alien registration or naturalization papers can complement what Angel Island records show.

Mexican and Latin American ImmigrantsMexican and Latin American Immigrants

While Angel Island is known for Asian immigration, Latin American travelers also passed through. Immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Central and South America occasionally arrived in San Francisco by ship, particularly if they were coming from ports on the Pacific coast (for instance, a ship from Panama or Mexico up to California). U.S. law did not impose immigration quotas on the Western Hemisphere before the 1960s, so Mexican immigrants were not barred like Asians. However, those who arrived by sea still had to go through immigration inspection. Some Mexicans and Latin Americans were sent to Angel Island if they were steerage-class passengers or if officials wanted to hold them for medical examination. These detentions were usually brief. For example, if a Mexican worker arrived ill or without clear documentation of a U.S. job, he might be held on Angel Island until a relative or employer in California could guarantee support. Records of Mexican and other Latin American immigrants at Angel Island may include passenger list entries (often listing nationality as “Mexican” or “Spanish” etc.) and possibly a Special Inquiry case file if there was an investigation. Some individual case files do exist – for instance, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation has highlighted the story of Catarino López, a Mexican immigrant whose immigration file is preserved in the archives. Genealogists researching Latin American ancestors should use passenger arrival databases and look for notations like “SI” (Special Inquiry) or “detained” on manifests, then follow up with NARA if a case file number can be identified. Additionally, don’t overlook U.S. census records – many Mexican immigrants who came via Angel Island settled in California and can be found in the 1920s–1930s censuses, which might indirectly confirm their approximate arrival date.

Filipino ImmigrantsFilipino Immigrants

The Philippines was a U.S. territory from 1898 until 1946, which gave Filipino immigrants a unique status. Prior to 1934, Filipinos were U.S. nationals and could travel to the mainland without visas or quotas. Many Filipinos came to the West Coast (often via Hawaii) as laborers, students (the Pensionado scholars), or military recruits. Because they were not legally “aliens” before 1934, Filipino arrivals generally were not detained at Angel Island for long – they typically only underwent standard medical checks and then were free to enter. As a result, few Angel Island records specifically document Filipino immigrants compared to other groups. After the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, Filipinos became foreign nationals with an annual immigration quota of 50, but by then Angel Island’s days were numbered (and the few who came under the quota could be processed on the mainland). A fire in 1940 and scant surviving paperwork make Filipino records at Angel Island sparse. If you are researching a Filipino ancestor, you may not find an extensive case file from Angel Island unless there were special circumstances. Instead, look at other records: passenger lists from ships arriving from Manila or Honolulu (they will list Filipinos on board), U.S. military records (if they enlisted after arrival), or Hawaiian immigration station records if they went through Honolulu. The Angel Island station did detain some Filipinos briefly for medical reasons, so a few names might appear in “held for inspection” logs. But in general, genealogists should note that Filipinos’ freedom of movement pre-1934 meant less documentation at entry. Once in the U.S., Filipinos appear in local records like employment files, selective service registrations, and the 1930 and 1940 censuses, which can be used alongside any Angel Island evidence.

Other Immigrant GroupsOther Immigrant Groups

Angel Island truly was a global gateway, and many other nationalities came through its doors. Some examples include: Pacific Islanders (such as people from Hawaii, Guam, or Polynesia – often traveling as U.S. nationals or with missionaries), Chinese from outside China (e.g. Chinese residents of Mexico or Canada re-entering via San Francisco, whose cases can be complex), Japanese Peruvians or other Latin Asians (people of Asian ancestry coming from Latin America, sometimes raising confusion in records), and European expatriates who had lived in Asia (for instance, a British citizen from Australia or Hong Kong arriving in California – usually processed quickly due to their status). Each of these instances produced records when detained. Generally, European-origin travelers and U.S. citizens were processed on board the ship and not detained at Angel Island. But if someone fell ill or did not have proper papers, Angel Island’s hospital or detention quarters might house them temporarily. For genealogists, if an ancestor doesn’t fit the main groups yet had a connection to the Pacific route between 1910 and 1940, consider checking Angel Island “hold” records. The National Archives’ lists of detained passengers (“Held for Special Inquiry”) include notations of all nationalities, and some case files in Record Group 85 (INS records) pertain to Greek, Armenian, Spanish, Persian, and other nationalities investigated at Angel Island. Always cast a wide net with spelling and naming variations. Remember that names were recorded by English-speaking inspectors who may not have captured the exact spelling from languages as varied as Arabic, Hebrew, or Samoan. The Angel Island era coincided with the tightening of U.S. immigration overall (the quota laws of the 1920s), so any non-Asian immigrants who fell afoul of paperwork might appear in the Angel Island files as well.

Types of Angel Island Immigration RecordsTypes of Angel Island Immigration Records

Researching the Angel Island experience involves piecing together several types of records. Understanding what these documents are and what information they contain will help navigate the archives effectively. Key record types include:

Immigration Case FilesImmigration Case Files

These are the core investigative files compiled by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) for individuals who underwent inspection or questioning. A case file often includes the immigrant’s application for entry, verbatim interrogation transcripts, affidavits from witnesses, reference letters or coaching documents, and official forms noting the decision (admitted or deported). The files frequently contain personal data such as the person’s age, place of birth, physical description, occupation, names of immediate family members, and sometimes maps or sketches (Chinese applicants, for instance, might have drawn maps of their home villages as part of their testimony). Many case files have photographs attached – typically small portrait photos taken at the time of interrogation. You may also find Certificates of Identity or Residence (for Chinese merchants and others who had such documents) and any correspondence or appeals related to the case. Some case files are thin (perhaps just a few pages if the person was quickly admitted), while others are hundreds of pages long, especially if the case involved multiple hearings or subsequent trips (each time an immigrant left and re-entered the U.S., officials might append new documents to the same case file). These case files are mostly housed at NARA’s San Francisco facility and are indexed by case number (more on finding these below). They are incredibly rich for genealogy – providing insights into family composition and even linkages to other relatives’ files (often the case file will reference related case numbers for parents or siblings).

Ship Passenger ManifestsShip Passenger Manifests

Every ship arriving at San Francisco had to provide a passenger list. These manifests are essential starting points for Angel Island research. They list each passenger’s name, age, sex, marital status, occupation, nationality, last residence, and intended destination in the U.S., among other details. Crucially, they often have annotations in the margin if a passenger was detained or had a case file opened. For example, manifests may have a stamp or writing like “SI” (Special Inquiry) next to a name, indicating the person was sent to Angel Island for investigation. They may also note the case file number or a “certificate of identity” number for Chinese travelers. The National Archives has microfilmed the San Francisco passenger lists for 1893–1953, and these are available online (for instance, on FamilySearch). There are also specialized lists, such as “Lists of Chinese Passengers Arriving… 1888–1914” and “Lists of Chinese Applying for Admission… 1903–1947”, which are indexes to Chinese entries. For genealogists, manifests provide the basic arrival facts: date, vessel, and initial screening information. They can help confirm your ancestor’s arrival and are often needed to locate the corresponding case file (since case files are organized by arrival date and ship – e.g., a Chinese case file number might include the ship arrival number and line number). Make sure to check both pages of the manifest (if two-page format) to see any “Disposition” or “Remarks” columns where detention is noted. Also note that many Chinese names on manifests were recorded in semi-anglicized form (e.g., “Lee, Foon (Chin)” indicating the person’s paper surname was Lee but real surname Chin). These little details can signal a lot about the case.

Interrogation Transcripts and TestimonyInterrogation Transcripts and Testimony

When an immigrant was detained for a special inquiry, a stenographer recorded the question-and-answer sessions. These interrogation transcripts are often the heart of Angel Island records for Asian immigrants. They capture the immigrant’s own words (through an interpreter if needed) and the often exhaustive questioning by officials. In Chinese cases, transcripts might involve dozens or even hundreds of questions, covering everything from “How many steps lead up to the front door of your house in China?” to “On what dates were your children born?” – all intended to verify identity claims. Other nationalities also had transcripts if subjected to inquiries (for instance, a South Asian immigrant might be grilled about his caste or military service, a Russian about political affiliations, etc.). These transcripts are usually found within the case file. In addition, Board of Special Inquiry (BSI) hearing documents fall in this category – a summary of the BSI’s findings and recommendations. For genealogists, the value of these transcripts is immense: they can reveal names of three generations of family members, details about life in the home country, and the immigrant’s personality and intelligence (as they navigated tricky questions). One should read them carefully for clues – for example, identifying the village mentioned and then linking that to geographical records, or noting the names of neighbors or witnesses (who might be relatives or fellow villagers who immigrated earlier). Keep in mind that interpreters’ accuracy varied; dialect differences sometimes led to confusion in the record. Also, if your ancestor gave coached answers, those answers might contain inaccuracies (since coaching books sometimes provided standard responses). If an interrogation transcript refers to a witness’s testimony, that testimony might be in a separate file or later in the same file (sometimes American witnesses or relatives were interviewed as well). Always check if the file has multiple transcripts (first hearing, any re-hearings, appeals, etc.).

Health and Quarantine RecordsHealth and Quarantine Records

Upon arrival, every immigrant underwent a physical examination by the U.S. Public Health Service doctors. Those who showed signs of contagious disease (trachoma, hookworm, tuberculosis, etc.) or failed the health requirements were held at the station’s hospital/quarantine facilities. The Angel Island hospital kept medical examination reports, quarantine logs, and vaccination records. While these are more bureaucratic, they can be important if your ancestor was hospitalized. A medical record might note an X-ray result, a course of treatment, or the outcome of a medical board hearing (for instance, whether a sick immigrant was allowed to stay or was deported on medical grounds). Some medical files are part of the individual’s case file; others might be found in separate Public Health Service records (Record Group 90 at NARA, which includes photographs of the station’s hospital and possibly patient lists. For genealogists, these records provide insight into the immigrant’s health and physical condition. A health inspection report usually notes height, weight, any scars or distinguishing marks, and if any vaccinations or procedures were done (e.g., delousing or fumigation were common for detainees’ belongings). If your ancestor spent time in quarantine, you might find references to them in Angel Island hospital registers or even local newspaper reports (in some cases, ships with contagious disease onboard were mentioned in papers). Keep in mind privacy restrictions are generally not an issue given the age of these records (over 80–100 years old), so if they survive, you can access them. Details like “failed eye exam due to trachoma” or “hospitalized 3 days for observation” could explain family oral history about a delayed arrival.

Photographs and Identification DocumentsPhotographs and Identification Documents

Many Angel Island case files contain photographs of the immigrants. Chinese and other Asian immigrants had photos attached to their paperwork such as Certificates of Identity, visas, or interrogation documents. These photos (usually passport-style headshots) are precious genealogical finds – you might discover the only known early photograph of your ancestor in their immigration file. Additionally, the files might include copies of personal documents the immigrant submitted: birth certificates, marriage certificates, business licenses, household registers from China, etc. For example, Chinese merchants often provided partnership papers or property deeds to prove their status; Japanese picture brides sometimes had marriage certificates from Japan; Indians might have letters of introduction from employers. These attachments may be originals or translations that were kept in the file. In cases of U.S. citizens or those with prior residence, you might also find things like Certificates of Citizenship (for U.S.-born Chinese returning from China) or permits to re-enter. If the immigrant had traveled before, earlier entry documents could be appended – such as a 1908 landing card included in a 1915 case file to show continuity. For genealogists, these items can be gold mines: a paper from the old country might list an exact village and parents’ names in Chinese characters, or a photo can be compared to family albums. Be aware that files sometimes contain multiple photos (e.g., one from each trip). Also, if an ancestor had siblings or a spouse who also immigrated, their case file might have a copy of your ancestor’s photo and vice versa, as families often cross-referenced each other’s cases.

Administrative and Legal CorrespondenceAdministrative and Legal Correspondence

In some cases, particularly complex ones, there will be letters and memos between immigration officials, or between the INS and the immigrant or their attorneys. If an immigrant appealed a denial, you might find transcripts of court proceedings or a judge’s ruling ordering their release (many Chinese who were U.S. citizens by birth filed habeas corpus lawsuits when initially denied). These legal records might not be in the NARA case file (they could be in court archives), but sometimes copies were included. Additionally, by the late 1930s, as attitudes shifted, you might see correspondence about the Chinese Confession Program of the 1950s (where Chinese who had entered under false identities were offered amnesty to confess). Note: Those confessions and resulting files are generally part of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)’s A-File system if done after 1944, but the NARA case file might reference if someone admitted a paper son relationship later. For genealogists, knowing if your ancestor had a legal case is important – it means you could also search federal court records (at the National Archives or Federal Records Center) for a case file of a court appeal, which can contain affidavits and testimonies mirroring or supplementing the Angel Island file.

In summary, Angel Island records range from passenger lists that place your ancestor on a ship, to thick case files with personal narratives. Using all these sources together will give the most complete picture. Next, we’ll look at how to locate and access these records step by step.

Locating and Accessing Angel Island Immigration RecordsLocating and Accessing Angel Island Immigration Records

Researching an Angel Island ancestor can be a multi-step process, as the records are primarily stored in archives (not all digitized) and can be under various finding aids. Here is a step-by-step guide to finding these records:

Step 1: Gather Key Details from Family SourcesStep 1: Gather Key Details from Family Sources

Begin by collecting any known information about your immigrant ancestor. This includes the person’s full name (and any alternate names), approximate birth year, and year of immigration (or at least a range). Talk to relatives and look for old documents or heirlooms:

- Old immigration papers: Does your family have any certificates of identity, residence, or a passport/visa? These can contain crucial data like a certificate number or arrival date. For example, a Chinese Certificate of Identity often has the entry date and ship name on the back.

- Naturalization certificates or alien registration cards: If your ancestor later became a U.S. citizen (or had to register as an alien in 1940), those papers might list an arrival date or ship.

- Personal accounts: Letters or diaries might mention the journey or detention. Even a note like “father was held at Angel Island for 2 weeks” is a clue that a case file exists.

- Photographs: Occasionally, detainees had group photos or individual portraits from their time at Angel Island. Check the backs of photos for dates or stamps.

Write down all names used: many immigrants had multiple names (e.g., an Anglicized name, a maiden name, a “paper” surname, etc.). You will want to search for each variant. Remember that in the records, the name will be what immigration officials recorded, which for Chinese and other Asians is usually a phonetic spelling. Make note if your ancestor’s Chinese name in characters is known, but keep in mind archives cannot search by Chinese characters – you’ll need a romanized version. Also, list any family members who traveled with or joined your ancestor, as their records may be intertwined.

Step 2: Search Passenger Indexes and Ship ManifestsStep 2: Search Passenger Indexes and Ship Manifests

The next step is to find evidence of your ancestor’s arrival in San Francisco. The easiest entry point is a passenger list because these are indexed and often digitized. Here’s how to proceed:

- Use Online Databases: FamilySearch has indexed collections of San Francisco arrivals. For example, FamilySearch offers “San Francisco Passenger Lists, 1893–1953”. Start by searching these for your ancestor’s name (try variant spellings). If your ancestor arrived during 1910–1940, their ship manifest should appear, listing them.

- Check “Held for Special Inquiry” Lists: FamilySearch also has a specific database called “Held for Special Inquiry Records, 1910–1941”. This is essentially an index of passengers who were detained (i.e., sent to Angel Island) during that period. If your ancestor’s name appears in this Special Inquiry index, it’s a strong indication they have a case file. The record may give you a case or certificate number as well.

- Extract Arrival Details: Once you find the passenger manifest entry, note the arrival date, ship name, and any annotations. For instance, a Chinese immigrant’s manifest might have a number like “14084/007-23” written next to the name – this is actually a case file number in code. It consists of a “ship series” number, page, and line. Even if such a number isn’t obvious, the manifest page and line number and the ship arrival date can help NARA staff locate the file. Also look for a column that says “Cause of Detention” or “Disposition”: if it says “Admitted” or “Deported” with a date, that’s useful timeline info; if it says “C.O.I. #____”, that’s a Certificate of Identity number tied to a case.

- Alternate Ports: If you suspect your ancestor arrived via Seattle, Portland, or Honolulu instead of San Francisco, you’ll need to check those ports’ records. Angel Island primarily handled San Francisco arrivals, but some people who ended up detained there technically landed in Seattle and were transferred down (rare, but during traffic overflow or policy quirks). Generally, focus on San Francisco records for Angel Island.

If initial name searches fail, try searching by just last name, or even by origin and year. Sometimes filtering by year of arrival and nationality can help identify misspelled entries. For example, a “Giuseppe Esposito” might be indexed as “Guiseppe” – searching for Italians in 1918 can zero in on him. For Chinese, if you know a relative’s paper surname, search by that surname and year. Keep track of possible matches – you might need to verify by age or companion travelers.

Step 3: Identify the Case File Number (if applicable)Step 3: Identify the Case File Number (if applicable)

Not every immigrant had a case file (only those who were questioned or detained beyond initial screening), but for those who did, knowing the case file number is the key to requesting the records. There are a few ways to get this number:

- Partial Name Index (EARS): The National Archives at San Francisco and UC Berkeley created an online index known as the Early Arrivals Records Search (EARS). This is accessible at casefiles.berkeley.edu (formerly also called the “90,000 name index”). Search this database for your ancestor’s name. If they are indexed, you’ll get a hit that includes a case file reference, which usually looks like a series of numbers and perhaps letters (for example, “Case 12345/12-8” or “File No. 5512/34”). Note that this index is not complete – it covers a large portion of files but not all.

- Derive from Manifest: If you found a manifest annotation, as described in Step 2, that might directly be the case number. For instance, in the Family Tree Magazine example, “Wah Lak” had manifest info leading to case #14084/007-23. In NARA’s scheme, a case number often has two parts separated by a slash: the first part is associated with the ship arrival (each ship on each voyage had an assigned number), and the second part combines manifest page and line or is a sequential number for that arrival. Write down any such numbers.

- Contact NARA with Details: If you cannot find an index entry or number yourself, you can skip ahead and ask the National Archives for help. The staff at NARA San Francisco can search their internal index if you provide sufficient information. Using the details from Step 2 (name, exact arrival date, ship, age, etc.), they can often identify the file and its number for you. In your inquiry, include all possible names and any numeric clues you have. It’s helpful to mention if the person traveled multiple times or had relatives with them, as sometimes the archive might find a file under a different entry date.

- Note on File Series: Most Angel Island era case files from San Francisco are part of Record Group 85 (INS), San Francisco District Office investigative files. Occasionally, if your ancestor re-entered via a different port later, their subsequent paperwork might be in another series or an A-File (see Step 5). But the initial case of arrival 1910–1940 will be in the SF District files. The case number we’re aiming for corresponds to that series.

By the end of this step, you ideally have either a case file number or at least confirmation that a file exists for your ancestor. If your ancestor was never detained (for example, a first-class passenger from England who didn’t go through Angel Island), you won’t have a case file – the manifest might be the only record of arrival. In that scenario, you can proceed to gather other records (census, etc.) instead of archival case files. But if a case file exists, proceed to Step 4.

Step 4: Request the Records from the National Archives (NARA)Step 4: Request the Records from the National Archives (NARA)

Armed with your ancestor’s details or case number, you can now seek the actual records from the National Archives. The primary repository is:

National Archives at San Francisco (San Bruno) – This archive holds the original Angel Island immigration case files and related records. There are a few ways to access them:

- Email or Write to NARA: You can send an inquiry email to sanbruno.archives@nara.gov (or a physical letter) including all the info you have . Clearly state you are looking for an immigration case file from Angel Island and provide name variations, date of arrival, ship, and case number if known. NARA staff typically respond within a couple of weeks with what they found. If the file is located and is not too large, they may offer to photocopy/scan it for a fee. (Many Angel Island files can be dozens or hundreds of pages, so copying costs might be significant, but you can request a quote.)

- Visit in Person: If you are able to visit the San Bruno facility, it’s recommended to contact them in advance with the case numbers you want. They will pull the files for you (some may be stored off-site and need advance notice). At the archive, you can view the original documents in the research room and make scans or photos. Personal visits can be very rewarding, as you can sometimes discover additional index volumes or staff expertise on-site.

- Request Digitization: As of recent initiatives, NARA San Francisco has worked on digitizing some of these files. In fact, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation notes that over 76,000 immigrant files (for birth years over 100 years ago) are available, and a few hundred have been put online. They even provide a link to “Angel Island Immigrant Records” in the National Archives Catalog. You can search within that series on NARA’s website; if you’re lucky, your ancestor’s file might already be scanned. If not, NARA can digitize on demand – you can request a file be scanned and emailed to you. There may be a cost, but it’s often worth getting high-quality digital copies.

- What to Expect: When you receive the file, it could be one document or a large packet. Handle the information systematically: note the file number and any references to other file numbers (e.g., if it says “See also File 12345/77 for wife”). If you get physical copies, keep them organized; if digital, create a folder for them.

Don’t forget that NARA also has microfilm of passenger lists and indexes which you might consult if needed. For example, if you didn’t already get the manifest, NARA can provide it. They have microfilm publications like M1410: Indexes to Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, 1893–1934 and M1411: Passenger Lists... 1893–1953. However, these are now mostly online, so in most cases you won’t need NARA to pull microfilm unless you want to double-check something.

Step 5: Explore Additional Resources and Related RecordsStep 5: Explore Additional Resources and Related Records

Once you have the core Angel Island records, there are a few further avenues and connections to consider:

- Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF): The AIISF is not an archive for the records (the records are at NARA), but it provides helpful resources and community knowledge. Their website’s “Family Research” section compiles links to the National Archives, finding aids, and even oral histories of Angel Island immigrants. Check if your ancestor’s story is mentioned in the Foundation’s “Immigrant Voices” or “Mosaic” stories – sometimes descendants share personal accounts that can supplement the official files. AIISF can also guide you to translations of the famous poetry or provide contacts for translators.

- USCIS Records (A-Files): If your ancestor remained in the U.S. past the 1940s, they might have a later immigration file known as an A-File (Alien Registration File). Particularly, many Chinese who had entered as “paper sons” later filed under the 1950s Chinese Confession/Amnesty Program – those records are part of A-Files maintained by USCIS. Also, any immigrant who was still alive after 1940 would have an Alien Registration Number from the 1940 Alien Registration Act. Some A-Files for older immigrants (born <1910-1920) have been transferred to NARA (notably to the National Archives in Kansas City or San Bruno in some cases). AIISF notes that if an immigrant’s birth was over 100 years ago, their A-File might be at NARA and searchable in the catalog. If your ancestor’s story continues (e.g., they naturalized in 1955, etc.), consider making a USCIS Genealogy Program request for their A-File or an Index Search to see if other files exist. (USCIS Genealogy Program handles A-Files with numbers below 8 million, among other record types.)

- Court Records: As mentioned earlier, a number of Angel Island detainees filed lawsuits. If you suspect your ancestor challenged a decision (there might be a hint in family lore or in the case file correspondence), you can inquire with NARA’s Pacific Regional court records or the National Archives in DC about case files from the U.S. District Court, Northern District of California. Many habeas corpus case files from the exclusion era survive and can be pulled by case name or date; they often contain duplicates of immigration documents and sometimes affidavits from relatives. For example, the famous court case of United States v. Gee Lee Bing might contain depositions from that Angel Island scenario.

- Regional Archives: While NARA San Francisco is the primary repository, note that some Angel Island-related records could also be in other archives. For instance, NARA Seattle holds files for the Seattle INS District – which sometimes include correspondence about transferring detainees or general policy that might mention individuals in passing. If your ancestor initially landed in Hawaii, NARA at Honolulu might have a file (Honolulu was another INS district with similar files). These are tangential, but worth keeping in mind if a search in SF comes up empty and you suspect a Honolulu or Seattle angle.

Finally, keep a research log of what you have checked and what you found. Angel Island research can involve many moving parts, and it’s easy to lose track. Document the sources (e.g., “Found case file #xyz at NARA, contains 32 pages, highlights: interrogation on Jan 5, 1923, photo included”), so you can reference or share this information later. In the next section, we will cover how to make sense of the information you obtain and connect it to the larger family tree.

Tips for Interpreting Angel Island DocumentsTips for Interpreting Angel Island Documents

The documents from Angel Island can be incredibly informative, but they may also contain archaic language, foreign text, or intentional obfuscations. Here are some tips to help interpret and contextualize what you find:

- Language and Translation: Many records will be in English (the language of the U.S. immigration bureaucracy), but they sometimes reference or include foreign-language content. Chinese immigrants’ files might contain Chinese characters – for example, in a village map label or in a sworn statement written in Chinese. If you’re not fluent, you may need help translating these. Consider reaching out to community organizations or using online forums where volunteer translators assist with Chinese genealogy documents. Even the transliterations can be tricky: e.g., “Lee Hung Chung” might correspond to the Cantonese surname “Lee” or “Li” in Mandarin. Understanding a few basic Chinese naming conventions (surname first, generational names, etc.) can be useful. The Angel Island case files often have an INS-produced summary that lists the “true name” if discovered, in Chinese characters; use that to verify family names in genealogical databases in China or Chinese American newspapers.

- Naming Conventions and “Paper Names”: Pay close attention to all names mentioned in the file. Chinese and other Asian immigrants often used aliases or “paper names.” For example, your ancestor may be referred to as “Wing Hop (alias Wong Fook You)” in the documents. Initially, this is confusing, but usually one is the assumed identity and one the real identity. If the file is post-1930s, sometimes the immigrant confessed the true name, which will be noted. Keep a list of each person’s alias vs real name. Also note how female immigrants are named – a Chinese female might be recorded only as “Wife of X” or with her husband’s surname, or sometimes with her maiden surname. Japanese women might be listed by maiden name in some documents and married name in others. Russian names might be Anglicized (e.g., “Ivanov” might appear as “John Ivanoff”). Use context to determine who is who. It helps to sketch a little family tree on paper as described in the file, including paper relationships (which might correspond to actual family if the paper family was often cousins, etc., or might be wholly fictitious).

- Reading Between the Lines: Remember that information in these records might be deliberately false or skewed. Chinese immigrants coached as paper sons memorized elaborate false family histories – so the interrogation transcript might detail an entire family that never existed. Use cross-references to sort fact from fiction. For instance, if the file says your ancestor’s father was a native-born citizen named “Chin Suey” who lived in San Francisco, check the U.S. Census or city directories to see if such a person existed. If not, that part might have been a fabrication. Conversely, some truth may slip in: maybe the paper uncle’s name was actually the immigrant’s second cousin in real life. Understanding the historical context (Chinese Exclusion, etc.) will help you empathize with why your ancestor might have provided misleading answers.

- Handwritten Annotations and Redactions: Many case files will have handwritten notes – perhaps an immigration inspector’s marginalia or later file room notes. These can be abbreviations like “B.R. 6-15-34” (meaning file was “Borrowed and Returned” on June 15, 1934) or “Dep 3/2” (meaning deported March 2). NARA staff sometimes redact privacy-sensitive info (though for records this old, that’s uncommon except perhaps for Social Security numbers if a document was added later). If you encounter a blacked-out section, check if it’s just a duplicate elsewhere unredacted. Also look for multi-page documents that might have been stapled out of order – ensure you’re reading in sequence.

- Translations and Summary Documents: In some files, especially for Chinese and Japanese, the INS included translated summaries of foreign documents or pre-interview summaries of the case (“Subject claims to be son of U.S. citizen so-and-so…”). These are gold because they condense key points. Use them as a roadmap but verify against the primary documents in the file. Occasionally, you might find the English translation but wish to see the original (say, a household register from China). If the original isn’t in the file, its content should be all in the translation. If there’s a dispute (like the translator noted something was unclear), you might consider consulting an expert with the copy you have.

- Historical Terminology and Context: Be aware of period-specific terms. For example, immigrants from India might be labeled as “Hindoo” in older documents regardless of actual religion. Asians might be described as “aliens ineligible to citizenship” (a legal term at the time for all Asians). Understanding laws can clarify file notes: if you see reference to Section 6 or Section 5 of some act, those are clauses of the Chinese Exclusion Act amendments (Section 6, for instance, allowed merchants to come). If the file mentions a Bond, that means the immigrant was released on an immigration bond (essentially bail) pending further appeal – those bonds might be found in the file as well.

- Gaps in the Record: If parts of the story seem to be missing, consider why. The 1940 fire at Angel Island destroyed some administrative records and correspondence, but fortunately, most individual case files survived (they were stored in San Francisco’s INS office, not on the island, and later transferred to NARA). However, it’s possible that your ancestor had a file but it’s not at NARA – for example, if they entered after 1940 or their case continued into the 1940s, the file might still be with USCIS or was merged into an A-File. In such cases, NARA might tell you “no record found.” Don’t be discouraged; that’s when a USCIS Genealogy request might find an A-File or a still-classified file. Also, sometimes female immigrants who came as derivatives (like a wife or child) didn’t get their own separate file; they might be included in the husband/father’s file. So if you don’t find a file for grandmother, but grandfather came through Angel Island, check his file for her documents.

- Seek Expert Help if Needed: Interpreting these files can be daunting. There are researchers and genealogists who specialize in Chinese Exclusion Act files and other Angel Island records. If you’re unsure about some aspect (say, reading old cursive handwriting of an interrogator), don’t hesitate to ask for help on genealogy forums or from archivists. Sometimes even the community at large has knowledge – for instance, someone else researching a paper family may have figured out part of the puzzle that overlaps with yours.

By approaching the documents critically and with cultural/historical sensitivity, you’ll be able to extract accurate genealogical information while understanding the circumstances under which it was recorded.

Incorporating Angel Island Records into Your Family TreeIncorporating Angel Island Records into Your Family Tree

Once you’ve obtained and interpreted the Angel Island records of your ancestor, the final step is to integrate this information into your broader family history research. These records are a starting point (or a missing chapter) that should be correlated with other sources to construct a full narrative. Here are ways to connect the dots:

- Confirm Identities with Census and Vital Records: Use details from the case file to find your ancestor and their family in U.S. census records. For example, if an Angel Island interrogation in 1913 mentions that the immigrant is joining a brother in Stockton, California, then check the 1910 or 1920 census for that brother’s household in Stockton. The age, occupation, and family members listed can verify that you have the right people. U.S. Censuses (1910, 1920, 1930, 1940) are particularly useful for tracking immigrants after they were admitted. Note that some Chinese and Japanese immigrants avoided census takers or used American nicknames, so you might have to search by first names or other family members. Also look for marriage records and birth certificates of children in the U.S. If the case file gives a marriage date or a spouse name, you can try to find a marriage license in county records. A birth certificate of a child might list the parents’ birthplaces and years in the U.S., which you can cross-check against the immigration timeline.

- Follow the Paper Trail of Later Life: Many Angel Island immigrants eventually naturalized as U.S. citizens. Chinese immigrants, for instance, could only naturalize after the laws changed in 1943 (and many did so in the 1950s). If your ancestor became a citizen, obtain their naturalization records (petition and certificate file) from NARA or the county court – these will often reference the immigration record (some naturalization petitions for Chinese explicitly note the old Certificate of Identity number or arrival date for verification). Similarly, if your ancestor registered as an alien in 1940, the Alien Registration form (Form AR-2) can be obtained through USCIS Genealogy and will list the date and port of entry (e.g., “Arrived SF 10/5/1923 per S.S. President Lincoln”). This can corroborate the Angel Island file and sometimes give additional info like current occupation in 1940.

- Connect Generations Internationally: Angel Island files often bridge the immigrant’s old world and new world. Use them to extend your tree back to the home country. For example, if a file provides the Chinese names of the immigrant’s parents and the ancestral village in Guangdong, you now have leads to seek out Chinese genealogy sources (such as clan genealogies or village records). If a Japanese picture bride’s file lists her family registry (koseki) information, you can request those records from Japan. For Russians, if the file mentions they were from a village in Siberia and were Mennonites, you can link that to church records of that community. The key is that Angel Island records often give the exact place of origin, which is crucial for international research. Moreover, by identifying siblings or cousins who might have also immigrated (or who stayed behind), you can research those lines to gather more family data.

- Compare Multiple Entries: Many immigrants through Angel Island did not come just once. Chinese merchants and students, for instance, traveled back and forth. If your ancestor has multiple case file numbers (perhaps one for 1912 and another for a re-entry in 1920), make sure you obtain all of them. Each entry might have different pieces of the puzzle (the 1920 file might mention a child born in the interim, etc.). Combining them provides a timeline of movements. Additionally, track if the person left the U.S. later in life. Some Angel Island detainees eventually returned to their homeland (voluntarily or via deportation). If they left, there might be an exit record or a Certificate of Departure. And if any family members later applied for immigration benefits (like a son sponsoring a father in the 1950s), those later files will refer back to the original arrival.

- Leverage Community and Historical Context: Place your ancestor’s experience in context by researching community histories. For example, if they were detained as part of a group of Sikh immigrants in 1913, read about Sikh migration and see if your ancestor is mentioned in secondary sources or newspapers of the time (the Sikh Foundation and other historical societies have written about cases of that period). If your ancestor was a “paper son,” the book “Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America” by Erika Lee and Judy Yung (2010) and other scholarly works provide context that can help you understand the pressures and decisions your ancestor faced. Sometimes academic works reference specific case files or individuals – you might get lucky and find a mention of your family if it was notable.

- Preserve and Share the Story: Now that you have these records integrated, consider writing down a narrative of your ancestor’s journey. Include the facts verified by records: “On March 12, 1923, Li Wong arrived in San Francisco Bay on the SS President Taft and was detained at Angel Island for 3 weeks. His interrogation reveals that he claimed to be the son of a U.S. citizen merchant, naming his home village as ___.” etc. By synthesizing the data with family lore (perhaps grandpa remembered his father talking about the Island), you ensure that this piece of family history is not lost. Moreover, you might share your findings with the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation’s Immigrant Voices project – they welcome family stories, which in turn helps other researchers and commemorates the experiences of those who came through the station.

Finally, remember that genealogical research is iterative. New information from Angel Island records might send you back to look again at earlier records with fresh eyes. For instance, knowing a true original surname might lead you to find a long-lost branch of the family under that name. Or, discovering that the “uncle” mentioned in the interrogation was actually a close family friend might prompt contacting that friend’s descendants to see if they have letters or photos of your ancestor. Angel Island records often unlock long-sought answers about when and how an ancestor came to America, and in doing so, open up new questions about their life before and after that moment. By diligently combining these unique immigration records with other genealogical data, you can piece together a more complete and human picture of your family’s journey.

Key Resources and ReferencesKey Resources and References

To assist in your research, here are some key resources and finding aids related to Angel Island immigration records:

- National Archives (NARA) – San Francisco: The primary repository for Angel Island case files. NARA’s “How to Inquire about Immigration Case Files from Home” guide provides instructions for requesting files . Contact info: 1000 Commodore Drive, San Bruno, CA; email sanbruno.archives@nara.gov; phone 650-238-3501. Always reach out ahead of a visit.

- NARA Online Catalog: The catalog entry “Angel Island Immigrant Records” (in RG 85) is searchable. Some files (especially A-Files for pre-1920 births) may be accessible digitally. Use the “Search within this series” feature.

- Early Arrivals Records Search (Case Files Index): Search the partial name index for San Francisco INS case files at casefiles.berkeley.edu (also known as the Bancroft Library index). This index covers tens of thousands of names and can provide case file numbers and basic info.

- FamilySearch Databases:

- “San Francisco Passenger Lists, 1893–1953” – free index and images of manifests (you need to log in with a free account).

- “Held for Special Inquiry, 1910–1941” – index of detained passengers (log in required).

- Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF): Their website has a section for Family History & Research, including research tips, a list of relevant archives, and examples of A-Files. AIISF staff can often guide you to resources if you hit a wall.

- Selected Bibliography: For deeper historical background and personal accounts, consider:

- Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America by Erika Lee & Judy Yung (2010) – comprehensive history (Angel Island Immigration Station - Facts, History & Legacy).

- Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910–1940 by Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, Judy Yung (1980, 1991) – includes translations of poems and oral histories.

- NARA’s Prologue article “The EARS Have It” by Lee Otten (Fall 2003) – details the creation of the case file index and contents of files.

- Paper Son: One Man’s Story by Tung Pok Chin – a memoir of a Chinese paper son’s journey through Angel Island (provides personal perspective).

ConclusionConclusion

By utilizing these resources and following the steps outlined above, you will be well-equipped to uncover and interpret the stories contained in Angel Island immigration records. This journey into the past not only enriches your family tree with factual data, but also honors the experiences of those who passed through Angel Island’s doors in pursuit of new lives in America.

Finally, remember that genealogical research is iterative. New information from Angel Island records might send you back to look again at earlier records with fresh eyes. For instance, knowing a true original surname might lead you to find a long-lost branch of the family under that name. Or, discovering that the “uncle” mentioned in the interrogation was actually a close family friend might prompt contacting that friend’s descendants to see if they have letters or photos of your ancestor. Angel Island records often unlock long-sought answers about when and how an ancestor came to America, and in doing so, open up new questions about their life before and after that moment.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Angel Island Immigration RecordsExplore more about Angel Island Immigration Records

- Angel Island’s Immigrants from 80 Countries: Stories from the West Coast Counterpart to Ellis Island - Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation

- Early Arrivals Records Search (EARS) - National Archives and Records Administration

- San Francisco INS Office Records - HistoryHub

- The EARS Have It: Doing an EARS Search National Archives and Records Administration

References