The household returns and ancillary records for the censuses of Ireland of 1901 and 1911, which are in the custody of the National Archives of Ireland, represent an extremely valuable part of the Irish national heritage. The 1911 census is one of only two Irish census records, along with the 1901 census, which survives in full prior to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. It was also the last census for the whole island of Ireland. Census records for 1821-51 were mainly lost during the destruction of the Public Record Office of Ireland in 1922. Only fragments of these census records remain, and these are also available on the National Archives of Ireland website.[1] Census returns for 1861 and 1871 were destroyed in 1877 after census data was analysed and the census reports published. The returns for 1881 and 1891 were destroyed in 1918 due to a paper shortage caused by the First World War.[2] No census was conducted in 1921 due to the unrest caused by the Irish War of Independence. The first census of the new Irish Free State was carried out on the 18th of April 1926. Under Irish legislation, there is a 100-year rule limiting the publication of Irish census records.[3] Current plans are for the 1926 census to become available to view for free on the National Archives of Ireland website on 18th April 2026.[4]

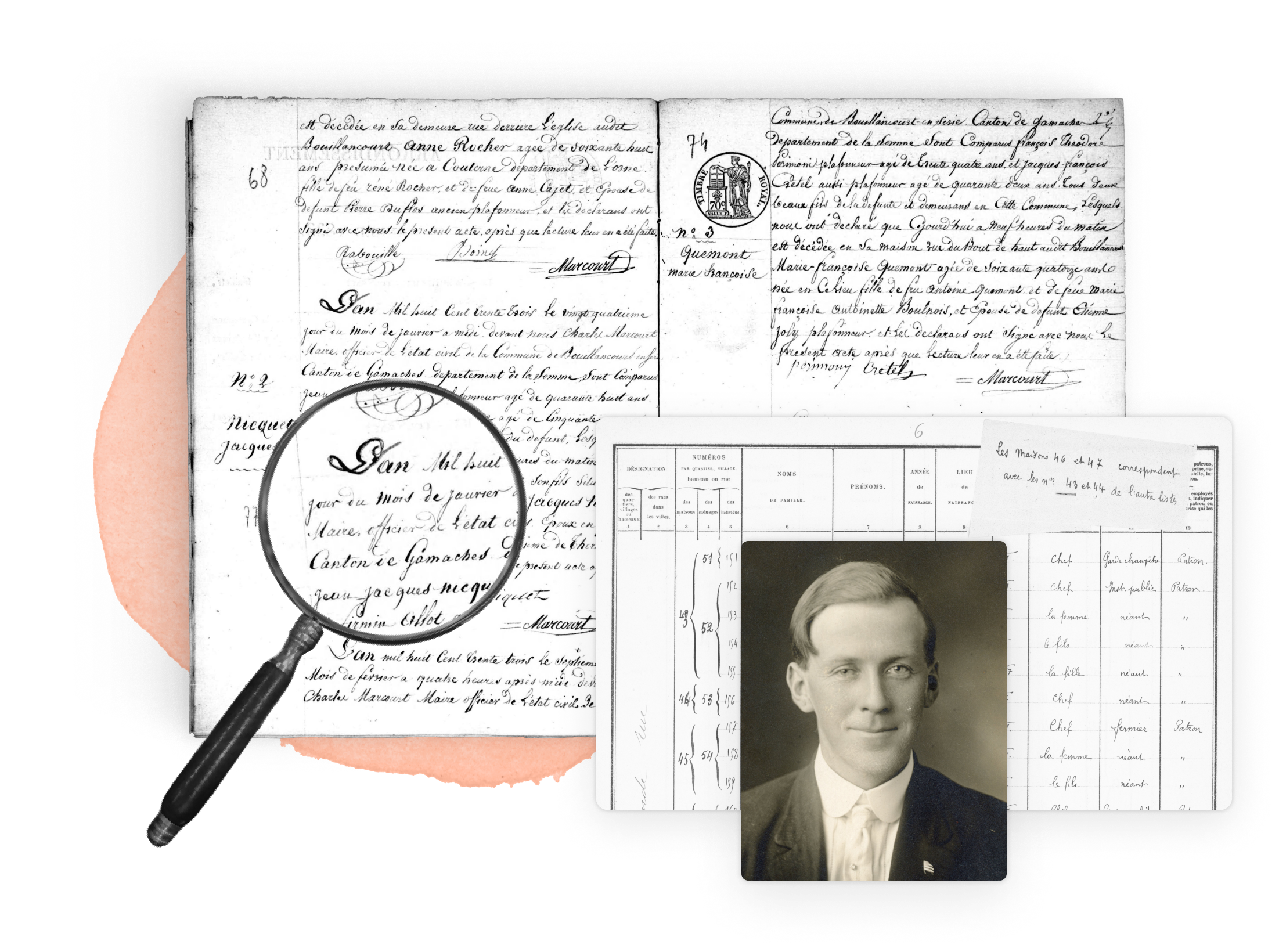

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Using the 1911 Census

The 1911 census of Ireland was taken on Sunday, the 2nd of April 1911. The total population of Ireland according to the 1911 census was 4,390,219, of whom 2,192,048 were male and 2,198,171 were female. In the weeks before census day, more than 4,000 census enumerators across Ireland had distributed the large blue census form to every home. As they moved from house the house the enumerators listed every head of household, before leaving behind the form to be filled in. Unlike in Britain where a specially-appointed civilian staff was recruited for the job, the enumerators in Ireland were drawn from the ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary. In Dublin, the constabulary was supplemented by 160 members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police.[5]

Ireland is unusual among English-speaking census-taking countries in that our original household manuscript returns survive. These are the forms filled out and signed by the head of each household on census night. Most other countries only have Enumerators' books, where family details were transcribed by the person charged with collecting the census information.[6] This means that when looking at the household return you can see the signature of the head of household.

The census form for Ireland was also different from that distributed in Britain. On the Irish form there was a question asking the religion of every person in a household. This question was not included in the British form. On the Irish form there was a question seeking to ascertain the number of Irish speakers in the country. In Britain, that question was asked of Welsh speakers. Finally, in Ireland the question was posed on whether people could ‘Read and Write’, ‘Read Only’, or ‘Cannot Read’.

When searching the census be aware of the administrative divisions used by enumerators. County; District Electoral Division; Townland or Street. This is a simple hierarchical structure which makes it easy to access any area in the country. The returns are arranged in clusters by townland/street within district electoral division within county. For each townland/street, there are a number of original household returns, filled in and signed by heads of households, and three statistical returns, dealing with religious denominations, classification of buildings, and out-offices and farm-steadings, filled out by the Enumerator for that townland/street.[7]

Contents of the 1911 Census

The returns for each townland or street in 1901 consist of:

- Forms titled Form A, filled in by the head of each household, giving the names of all people in that household on census night and their age, occupation, religion and county or city of birth (or country of birth if born outside Ireland); and particulars as to Marriage (marital status, length of marriage, number of children born alive, number of children still living).

- Forms (titled Forms N, B1 and B2) filled in by the census enumerator official taking the census, summarising the returns for that townland or street.

As well as surname searches, the returns may be searched by religion, occupation, relationship to head of family, literacy status, county or country of origin, Irish language proficiency, specified illnesses.[8]

Be aware however, that there may sometimes be a mismatch in ages between the 1901 and 1911 census. Sometimes an individual may appear to age more or less than the expected decade. As such it is important to use records such as baptismal registers and civil records to confirm an individual’s exact age, rather than simply relying on the census. It wasn’t until the introduction of the old age pension in 1908, that many people had a reason to be keep a more accurate track of their age.[9]

Like the 1901 census, the 1911 census also has a number of missing townlands which have not been indexed. Some of these are online as images and simply haven’t been indexed, others exist only on microfilm and have not been digitised, and some were never microfilmed originally. There are also a handful which are simply missing.[10]

Differences from the 1901 Census

The 1911 census form asked a number of new questions focused on marriage and children to accumulate data on fertility and infant mortality rates between classes, which some women regarding as invasive.[11] For example, married women were required to state the number of years they had been married, the number of their children born alive and the number still living.[12] For researchers in the present, this information is invaluable, because the civil death registers can be used to track children who died between 1901 and 1911. It also offers an insight into life at the time. Given the harsh conditions experienced by the poor in Ireland at the time, it was not unusual for there to have been a high mortality rate among young children. Dublin tenements, in particular, housed tens of thousands of extremely poor families who lived in appalling circumstances.

See also

Explore more about the 1911 Ireland census

- 1911 Ireland Census record collection at MyHeritage

- Getting the Most out of the Irish Census webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- The Three Cs of Irish Research: Civil Registration, Church Records, and Census webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Foundations of Irish Genealogy 7: Census Substitutes webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Foundations of Irish Genealogy 3: The Major Records II, Censuses webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/pre1901.html

- ↑ https://www.cso.ie/en/census/censusthroughhistory/

- ↑ https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1993/act/21/section/35/enacted/en/html

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/ireland-bids-to-woo-heritage-hunters-with-us-and-uk-launch-events-for-release-of-1926-census-records/a1065028916.html

- ↑ http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/exhibition/dublin/census_day.html

- ↑ https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/about19011911census.html

- ↑ https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/about19011911census.html

- ↑ https://www.nationalarchives.ie/article/official-returns-substitutes/

- ↑ https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn04817/

- ↑ https://www.johngrenham.com/browse/missing_1911.php

- ↑ https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-1916/1916irl/cpr/cwr/c1911/

- ↑ https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/about19011911census.html