The 1870 U.S. Federal Census – the Ninth Decennial Census – offers a crucial snapshot of Americans in the post-Civil War era. Taken just five years after emancipation, it was the first census to list all formerly enslaved individuals by name, marking a turning point for African American genealogy. It also introduced new data categories, including expanded racial designations and detailed economic and social statistics, reflecting the nation’s changes after the war. This article will explore all major schedules compiled in 1870, provide practical tips on accessing and interpreting these records, and discuss special considerations such as new racial categories and regional variations.

Major Schedules of the 1870 CensusMajor Schedules of the 1870 Census

The 1870 census consisted of several different schedules (record types), each capturing a different aspect of life in that year. The primary Population Schedule (Schedule 1) recorded individuals and households. In addition, Non-Population Schedules collected information on specific topics: Agriculture, Industry/Manufacturing, Mortality (deaths in the year prior), and Social Statistics. These schedules complement each other and can provide a fuller picture of your ancestors’ lives and communities. The table below outlines the key differences between each 1870 schedule and the data points collected:

| Schedule (1870) | What It Recorded | Key Data Collected | Genealogical Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population (Inhabitants) | Everyone living in each household as of the official census date (June 1, 1870). | Name of every person in the household Age Sex Color Occupation or profession Value of real estate owned Value of personal estate Place of birth (state or country) Whether father of foreign birth Whether mother of foreign birth If born within the year If married within the year Attended school within the year Cannot read or write (if age 10 or older) Whether deaf, dumb, blind, or insane (if applicable) Male citizen of U.S. age 21 or older Male citizen age 21+ whose right to vote was denied (except for rebellion or crime) |

High. Provides full names and personal details for every individual, making it the most important schedule for genealogists. Household groupings imply family relationships, and data such as ages and birthplaces are vital for tracing and linking family members. |

| Mortality | Individuals who died during the 12 months preceding the census (June 1, 1869 – May 31, 1870). | Name of deceased person Age at death Sex Color Marital status (married or widowed) Place of birth Month of death Cause of death Occupation (if applicable) Number of days ill |

High. Records deaths that occurred in the year before the census, including details not found in the population schedule. Useful for identifying ancestors who died between censuses and for obtaining death information (age, date, cause) before civil vital registration was established. |

| Agriculture | Data on farms and agricultural production for each farm owner or manager. | Name of farm owner/manager Acres of land (improved and unimproved) Value of farm (land and buildings) Value of farming implements and machinery Value of livestock Number of farm laborers employed (and sometimes their wages) Quantities of major crops produced (bushels, bales, etc.) Counts of livestock (horses, cattle, sheep, swine, etc.) |

Moderate. Lists only the farmer (head of household) by name, but offers insight into the economic status and operations of an ancestor’s farm. Confirms an ancestor’s occupation as a farmer and provides context about their livelihood (farm size, crop production, livestock), enriching the family history narrative. |

| Industry (Manufacturing) | Data on industrial and manufacturing establishments in the area. | Name of business, company, or owner Type of establishment (industry) Capital invested Number of employees Total wages paid Raw materials used (type, quantity, value) Products manufactured (type, annual quantity and value) |

Low. Includes names of business owners or manufacturers, but only for those meeting certain production thresholds. Useful if an ancestor owned or operated a business (details the enterprise’s scale and output). Otherwise of limited genealogical use, since it does not list the general population. |

| Social Statistics | Various community-level statistics (no individuals listed). | Aggregate information for each locality, such as assessed property values (real and personal) Taxes collected Public debt School statistics (number of schools, teachers, students) Literacy rates Libraries Churches (number by denomination) Paupers and criminals supported at public expense Average wages Newspapers published in the area (names and frequency) |

Low. Contains no personal names. Mainly useful for historical context, providing insight into the community where an ancestor lived (local economy, education, religion, etc.). May also yield clues for further research – for example, identifying local churches or newspapers that could be sources of individual records. |

As you can see, the Population Schedule is the most genealogically important for identifying individuals. However, the non-population schedules (Agricultural, Manufacturing, Mortality, Social Statistics) can greatly enrich your research.

Population Schedule: Every Name CountsPopulation Schedule: Every Name Counts

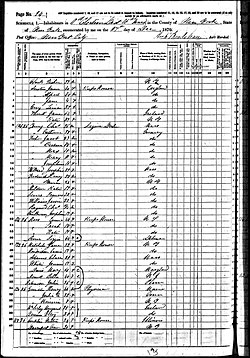

The Population Schedule of 1870 (Schedule 1, “Inhabitants”) recorded every person by name in each household, making it incredibly valuable to genealogists. Enumerators were instructed to list “the name of every person whose place of abode on the first day of June, 1870, was in this family.” For each individual, a wealth of information was captured in 20 columns:

- Identification: Dwelling number and family number in order of visitation.

- Personal Details: Name, age (with infant ages in months if under 1 year), sex (M or F).

- Color (Race): Marked as White (W), Black (B), Mulatto (M), Chinese (C), or Indian (I). This was the first census to include “Chinese” and “Indian” as specific race categories, reflecting the presence of Chinese immigrants and Native Americans in the population.

- Occupation: Profession, occupation, or trade for each person (including women and children if they had jobs). Notably, 1870 was the first census to list occupations for all individuals, regardless of sex or age.

- Property: Value of real estate owned and personal estate (personal property) for each individual. This can indicate the household’s wealth, though many (especially in the South after the war) had “0” or blank if they owned little property.

- Place of Birth: The state or territory if born in the U.S., or country if foreign-born.

- Parentage: Two columns indicating whether the person’s father was foreign-born and whether the mother was foreign-born (usually marked with a tick or hash if “yes”). These new columns in 1870 are extremely useful—if you see a mark here, it implies your ancestor was a first-generation American, pointing you to look for immigrant parents’ origins.

- Birth/Marriage in Year: If born within the census year (June 1869–May 1870) the month of birth was noted, and similarly if married within the year, the month of marriage was noted.

- Education: Columns noting whether the person attended school within the year, and whether they cannot read or cannot write (illiteracy indicators). In 1870, unlike earlier censuses, literacy was inquired of all individuals over age 10, not just those over 20, so it gives a fuller picture of community literacy.

- Disabilities: A column if the person was deaf & dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic (using the 19th-century term for developmental disability). Enumerators would write an abbreviation or check here if applicable.

- Constitutional Relations: Two unique columns added in 1870 reflecting Reconstruction-era concerns. Column 19 asked if the person was a male US citizen 21 or older (which would include most adult men). Column 20 asked if any such male citizen’s right to vote was denied or abridged for reasons other than rebellion or crime. This was intended to measure enforcement of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution (and, by 1870, the 15th Amendment) regarding African American suffrage. In practice, this column was often underreported or left blank by enumerators, but if your ancestor has a mark here, it suggests they were denied voting (likely due to race or other disenfranchisement law in their state).

Genealogical Tips – Population Schedule: The population schedule is often the first stop in research. Use it to identify family groups – everyone living in the same household will be listed together. Keep in mind that relationships were NOT stated (the census did not yet have a “relationship to head of household” column in 1870). Generally, the first person listed is the presumed head of household, and others are likely relatives or boarders, but be cautious: children listed may be nieces/nephews, adopted kids, or unrelated individuals. Always corroborate relationships with later censuses (1880 and on, which do list relationships) or other records.

Pay attention to spelling variations and handwriting. Many Americans in 1870 could not read or write, so they could not spell their own names for the enumerator. Enumerators often wrote names phonetically or made mistakes, and those errors “could easily have stayed that way” in the record (united states - How did US census takers record household information? - Genealogy & Family History Stack Exchange). For example, a name like “Catherine” might appear as “Catharine” or “Katherine,” or an enumerator might mis-hear an accented surname. When using indexes or searching online, try variant spellings. If possible, view the original handwritten image – deciphering 19th-century handwriting can be challenging, but you may catch transcription errors or additional details (like middle initials or notes) by examining the image yourself.

Another quirk: enumerators sometimes used ditto marks (written as "do" or just quotation marks) to repeat the same surname or place of birth for people in a household. So if only the first person’s last name is written and others just have ditto marks, the transcription might omit the surname for the others or carry it incorrectly. Be mindful of the enumeration date too. The official census day was June 1, 1870, but not everyone was visited on that day. Enumerators conducted the census over several months (officially due by Sep 10, 1870), and some areas were even enumerated in early 1871 for a second count. The date the enumerator visited your ancestor’s household is usually written at the top of the census page. If your ancestor’s information was recorded in, say, August 1870, it should still reflect their status as of June 1 (for instance, a baby born in July should not be listed, while a person alive on June 1 but who died in July should still be listed as living). Not all enumerators strictly followed this rule, but it’s a good thing to remember if you notice discrepancies in ages or missing infants.

Finally, African American ancestors present a special case in 1870: this is typically the earliest census where they appear by name (if they were enslaved prior to the Civil War). The 1870 census is sometimes called the genealogical “brick wall” for African Americans—it’s the critical starting point to trace formerly enslaved ancestors. Be prepared for challenges: many freed people adopted new surnames after emancipation, often changing from the last name of a former enslaver to a different family name, or spelling it differently. You may need to search creatively (by given name, age, first initial, etc.) to find them in 1870. Once found, however, the 1870 entry can unlock further research: you can look for the same individuals in 1880, or in Freedmen’s Bureau records (1865–1868) and Freedman’s Bank records to gather more information linking them back to the slavery period.

Agricultural Schedule: Farming and LandholdingsAgricultural Schedule: Farming and Landholdings

If your ancestor was a farmer in 1870 (as many Americans were), the Agricultural Schedule can be a goldmine of information. The agricultural schedule (Schedule 3, “Production of Agriculture”) listed each farm or plantation and collected data about land use, farm value, and production. Importantly, it names the owner, agent, or manager of each farm – so if your ancestor owned or ran a farm, you should find their name here, typically in the same county where they appear in the population census.

What’s in the Agricultural Schedule? This schedule recorded extensive details for each farm, including:

- Name of Owner, Agent, or Manager. This is usually the head of the household who was listed as a farmer in the population schedule. (If a family rented land, the owner’s name might be listed, or the tenant noted as the manager.)

- Acreage: Acres of land broken down into “improved” (cultivated or used) and “unimproved” (woodland or unused) acres.

- Farm Values: Cash value of the farm (land and buildings), value of farm machinery and implements, and value of livestock.

- Livestock: Number of animals of various types (horses, milch cows, working oxen, other cattle, sheep, swine, etc.) that the farm had on hand. This can tell you if your ancestor had, for example, a small subsistence farm with just a few pigs or a large operation with a herd of cattle.

- Crop Production: Quantities of major crops produced in 1869. Common crop entries include bushels of wheat, corn, oats, barley, rye; bales of cotton; pounds of tobacco; pounds of wool; bushels of potatoes; value of orchard products; gallons of wine; etc., depending on the region’s products. Also, value of forest products (like lumber or firewood sold) if applicable.

- Other Outputs: Number of pounds of butter and cheese produced, gallons of milk sold, eggs produced, and so on, plus value of animals slaughtered in the past year. The schedule aimed to capture the total agricultural output of each farm in the census year.

One critical note: not every farmer will appear, because small farms below a certain threshold were excluded. By 1870, farms of less than 3 acres or that produced less than $500 worth of products in 1869 were not recorded on the agricultural schedule. So, if your ancestor was a very small-scale farmer (perhaps just growing food for the family with minimal surplus), they might not be listed. In the population schedule they could still be called a “farmer,” but they may not have met the census cutoff for the agriculture schedule. In that case, consider local tax records or deed records for information on their land, since the census skipped them.

Using the Agricultural Schedule: For genealogists, this schedule adds depth to an ancestor’s profile. Once you find your ancestor in the population census as a farmer, look for them in the agricultural schedule of the same county. You’ll likely find their name with data that tells you the scale of their farm. For example, you might discover that your great-great-grandfather John Doe had 50 improved acres and 100 unimproved acres, 2 horses, 3 milk cows, 10 sheep, produced 200 bushels of corn and 5 bales of cotton, etc., with a farm valued at $1,000. This paints a vivid picture of his daily life and economic situation – perhaps a modest farmer, or maybe a relatively large landowner for his area.

Compare the agricultural data with the population schedule details: Does the reported real estate value on the population schedule match the farm value? (They won’t be identical but should be in the same ballpark; any major discrepancy might indicate an error or that the land was owned by someone else.) Look at neighbors in the agriculture schedule as well – farms were often listed in the same order as the population schedule, so neighboring entries could be your ancestor’s actual neighbors, possibly relatives or known community members.

If your ancestor was an African American farmer in 1870, finding them in the agricultural schedule is especially meaningful. Many formerly enslaved people became sharecroppers or small landowners after the war. If they managed to own land, their inclusion in the agriculture schedule with even a few acres is a testament to their progress just a few years after emancipation. Keep in mind that if they were sharecropping on someone else’s land, the owner’s name might be listed instead. You may have to search by location or owner’s name to find the farm data and then deduce your ancestor’s output. Freedmen’s Bureau records and land deeds can help confirm land ownership or tenancy arrangements in such cases.

Industry and Manufacturing Schedule: Businesses Big and SmallIndustry and Manufacturing Schedule: Businesses Big and Small

The Industry/Manufacturing Schedule (Schedule 5, often called the manufacturing schedule) recorded data on America’s businesses in 1870. This schedule is useful if your ancestor was involved in manufacturing or trade – for instance, if they owned a mill, a workshop, a mine, or a factory, or even a smaller enterprise like a blacksmith shop or a lumber operation. It’s also a rich source of local history, showing the economic activity of the area.

What’s in the Manufacturing Schedule? For each establishment or business, the census collected details such as:

- Name of the business or manufacturer. Sometimes this could be a company name (e.g. “Acme Milling Co.”) or an individual’s name if it was a small proprietorship.

- Type of establishment or product. They would note what the business was (e.g. grist mill, cotton textile mill, iron foundry, shoemaker, carpenter, cheese factory, etc.).

- Capital invested. How much money was invested in the business.

- Raw materials used. Types and quantities of raw material consumed in the year (for example, a lumber mill might list the number of logs or board-feet of wood; a bakery might list barrels of flour used).

- Annual production. Quantities and value of products produced in the year. For instance, a flour mill might list how many barrels of flour; a blacksmith shop might give an annual earnings figure.

- Power and machinery. The kind of power used (steam engine, water power, hand power) and any machinery details. In 1870, industrial technology was a hot topic, so noting steam vs. water power, etc., was important.

- Employees. Number of “hands” employed, often divided by men, women, and children, and sometimes by age group. The schedule also captured the average monthly cost of labor or total wages paid.

- Exclusions: Like the ag schedule, very small businesses were excluded – those producing less than $500 in goods annually were generally not listed (Nonpopulation Census Records | National Archives). So a one-man craftsperson who produced very little might not appear.

For example, if your ancestor ran a blacksmith shop, the manufacturing schedule might list something like: John Smith – Blacksmith – capital $200 – 2 employees (maybe himself and an apprentice) – using say X pounds of iron – producing wagons, tools, horseshoes, etc. worth $800 in the year – paying $300 in wages. On the other hand, a large textile mill in the same county might show thousands of dollars in capital, dozens of workers, and significant output. This lets you gauge where your ancestor’s business stood in the local economy.

Using the Manufacturing Schedule: Genealogists can search this schedule by county and look for surnames or business names that match their family. If your ancestor listed an occupation like “miller,” “wagon maker,” “manufacturer,” “shoemaker,” or “mine operator” on the population schedule, definitely check the manufacturing schedule. If they were an employee (say a factory worker), they won’t be named on this schedule (only owners/operators are named), but you might still glean context. For instance, if many in your family’s town worked in a certain mill, finding that mill’s entry will tell you about the scale of that employer.

Keep in mind that some businesses were seasonal or small-scale; if you don’t find a likely candidate, try looking at the population schedule for others in the area with similar occupations – maybe a neighbor with the same trade who does appear in the industry schedule, which can indirectly tell you about your ancestor’s work. City directories of the late 1860s or 1870s can also help identify business names to look for.

Sometimes the manufacturing schedules are organized by type of industry rather than strictly by location. So all mills might be listed together, for example. Read the headings and arrangement carefully, or consult finding aids (the National Archives microfilm catalogs often have introductory notes about arrangement).

In sum, while the manufacturing schedule is more of a bonus for genealogists, it can be very rewarding. It’s one thing to know an ancestor was a miller; it’s another to see that his mill ground 5,000 bushels of grain that year with two waterwheels turning – bringing that ancestor’s occupation to life.

Mortality Schedule: Finding Ancestors Who Died in 1869-1870Mortality Schedule: Finding Ancestors Who Died in 1869-1870

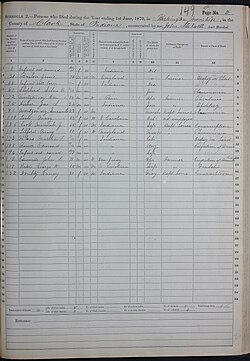

The Mortality Schedule (Schedule 2) is a special part of the census that listed people who died in the 12 months immediately before the census. For the 1870 census, it covers deaths from June 1, 1869 through May 31, 1870. This schedule can be invaluable for genealogists because civil death registrations were sparse in this era – many states did not keep systematic death records yet. The mortality schedule might be the only recorded evidence of an ancestor’s death and details surrounding it.

What’s Recorded in 1870 Mortality Schedules? Each entry in the mortality schedule is like a death certificate in census form. Columns include:

- Name of the deceased. (Only people who died in that one-year window are listed.)

- Age. Given in years, months (if under 1 year), or days for infants.

- Sex and Color (Race). As with the population schedule, race was indicated (W, B, M, C, I) – and 1870’s mortality schedules explicitly distinguished Chinese and Indian decedents if any (Decennial Census Questionnaires & Instructions).

- Marital Status. Typically noted as married or widowed (unmarried persons often have blank, implying single).

- Place of Birth. State or country of birth.

- Month of Death. The calendar month in 1869 or early 1870 when the person died (important for narrowing down exact date or finding a newspaper obituary which often were by month).

- Occupation. Yes, even the deceased’s occupation was listed, giving a clue to their role in life (e.g. a farmer, housewife, miner).

- Cause of Death. This can range from specific diseases (“typhoid fever”, “consumption” (tuberculosis), “childbed fever”) to broad terms (“dropsy” for edema, “old age”) or tragic causes (“burned in fire”, “drowned”). Causes of death provide insight into health and hazards of the time.

- Length of illness. How long they were ill with that final sickness (e.g. “3 days”, “2 months”), which helps indicate sudden vs. long-term illnesses.

These schedules sometimes had additional remarks by the enumerator or attending physician on the back side of the form. For 1870, typically you get the main details on the front; a few states or enumerators might have added notes. (Researchers have noted that in 1880, physician follow-ups were included on the back, and for 1870 it was less common to have extensive notes, but always check if the archive provides images of both sides of a mortality schedule page.)

Using the Mortality Schedule: First, if you suspect an ancestor died around 1869-70 (for example, they appear in 1860 census but by 1870 the family is there without them), check the mortality schedule for their county. It’s organized by county (and sometimes by sub-division within the county, like a specific city or district) just like the population census. If you find your ancestor, you not only confirm their death, but you get that extra detail of cause of death and timing.

Even if you don’t suspect an ancestor’s death, it can be worth scanning the mortality schedule after you’ve looked at the population schedule. Sometimes people do not show up in 1870 population because they died just before the census – they won’t be in the household listing, but they will be on the mortality schedule. For example, if a child born in 1860 is missing in 1870, check if they perhaps died in childhood and show up in mortality. Or an elderly relative who was in 1860 could have passed by 1870; the mortality schedule might record that.

Mortality schedules can also contain people in institutions (hospitals, prisons, poorhouses) who died – they might be listed there even if they weren’t local residents. So if an ancestor isn’t where expected, consider that they might have died while away and could still appear on a mortality schedule of wherever they passed.

Another tip: The mortality schedule can list causes of death that run in families (like if many died of consumption/tuberculosis) or reflect historical events (a cluster of “cholera” might indicate an epidemic in that area). It provides context for challenges your ancestors faced.

For genealogists, once you have a death from the mortality schedule, you can seek out other records like a church burial register, a gravestone, or a newspaper death notice from that time frame to add or corroborate information. But often the mortality schedule itself will be the earliest and most informative source for that death.

Social Statistics Schedule: Community ContextSocial Statistics Schedule: Community Context

The Social Statistics Schedule (Schedule 4) is different from the others in that it doesn’t name any individuals at all. Instead, it gathers community-level data for each county, city, or other civil division. While this schedule is less directly useful for specific ancestor information, it’s still worth knowing about for the rich contextual background it provides for the places your ancestors lived.

What did the Social Statistics schedule include? The 1870 social statistics schedule asked local officials or enumerators to report on things like:

- Taxation and Property: The total value of real estate and personal property in the area, and the annual taxes (county and town taxes, for instance). This gives a sense of the wealth of the community.

- Education: Number of schools, how many teachers and pupils, literacy rates indirectly (by number of people who can read/write perhaps reported elsewhere), etc.

- Libraries and Newspapers: The number of libraries (public or institutional) and the number of volumes they held; the names of newspapers published in the area and their circulation figures.

- Churches: Number of church organizations by denomination, the number of church buildings, and the seating capacity of each (a way to gauge the size of congregations), as well as the value of church property.

- Pauperism and Crime: The number of people receiving public assistance (“paupers”) and the cost of supporting them, often broken down by native vs. foreign-born and by race (“native black” vs “native white”). Also, the number of criminals in prison, again often broken down by nativity and race.

- Wages: Average wages for common occupations – e.g. average daily wage for a farm laborer, a day laborer, average monthly pay for a live-in domestic, etc. This helps you understand what an income might have been in that locale.

- Miscellaneous: In earlier censuses, social stats sometimes included info on colleges, insane asylums, number of deaf/blind in the county, etc. For 1870, much of that information was streamlined and some of it (like counts of insane, blind, etc.) was moved to the population schedule’s own columns (column 18). The 1870 social statistics still focus on institutions and economy at large rather than individuals.

Because this schedule is statistical, its direct genealogical use is limited. However, it’s a fantastic background resource. For example, if you’re writing a family history narrative and want to describe what your ancestors’ county was like in 1870, the social stats can tell you that “X County had 3 churches (2 Methodist and 1 Baptist) and 1 newspaper with a circulation of 500, and the total real estate valuation was $1,000,000” etc. If your ancestor was a teacher or a minister, these figures take on personal meaning (how many pupils might they have taught? how large was their congregation?).

Sometimes you might find a tidbit that intersects with your family: for instance, if an ancestor was in the poorhouse, the number of paupers and cost is listed (though not their names). Or if an ancestor was a known criminal or in jail, the count of prisoners tells you roughly how many others were in that jail. It’s all part of painting a fuller historical picture.

Access note: The social statistics schedules can be a bit hidden in archives and are not always digitized widely, since genealogists use them less. Many of these schedules survive and are available at the National Archives or on microfilm. Some state archives might also have information extracted. If you can’t find it easily online, check the National Archives’ catalog or state historical society publications that might summarize local social statistics.

How to Access 1870 Census Records (Population and Non-Population)How to Access 1870 Census Records (Population and Non-Population)

Accessing the 1870 census records is easier than ever, thanks to digitization. Here are the main ways to find these records:

- Online Genealogy Databases: The complete 1870 Population Schedule has been digitized and indexed. MyHeritage has 1870 Census Population Schedule images (https://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-10128/1870-united-states-federal-census). The images come from National Archives microfilm publication M593 (1,009 rolls). You can search by ancestor’s name and navigate to the census page image.

- National Archives (NARA): The National Archives in Washington, D.C., and regional branches have the microfilm for 1870. You can visit in person and view microfilm M593. However, since images are online, most researchers won’t need to use microfilm. If you want a high-quality copy, the National Archives’ website also provides direct digital images; their 1870 census page has links to the original schedules online. The National Archives does not have the 1870 schedules available in original paper form for research use – they were long ago transferred to microfilm for preservation. But copies of original might exist at state archives in some cases (like the state copies for Minnesota, discussed below).

- State Archives and Libraries: Some states had duplicate copies of the census (1870 was still conducted by federal marshals, but in some states a copy was filed at a state level). Notably, for Minnesota, the federal copies for many counties were destroyed, but the state copy survived. The Minnesota Historical Society has those, and they have also been microfilmed as series T132. Today, those Minnesota records are also online, but it’s good to be aware of such cases. Additionally, some state archives have non-population schedules in original or microfilm form. For example, the Florida State Archives has the mortality schedules for 1870 available online for Florida. Check state archive digital collections for things like “1870 agricultural schedule [State]” or “mortality schedule [State]”.

- Libraries and Societies: Local genealogical societies or libraries might have census records on microfilm or even printed transcriptions/indexes (older publications might have transcribed the 1870 census for a county in a book, useful for quick reference but always verify with the image). They may also have Soundex indexes or other finding aids, but Soundex was not created for 1870 (it exists for 1880 and later selected censuses). For 1870, we rely on modern indexes.

- Published Abstracts: In some cases, historical or genealogical journals have published abstracts or extracts of 1870 non-population schedules. For instance, an agricultural schedule might be transcribed in a local history book. This can be a shortcut if available, but given the volume of data, most people will use the originals.

When searching online, remember to try both name searches and location browsing. If your ancestor’s name is uncommon or you have precise location, a name search will usually suffice. If the name is common or spelled oddly, you might browse to the county and then find the enumeration district to scroll. FamilySearch’s catalog can help identify microfilm rolls for a specific county if you want to browse that way.

For the Non-Population Schedules (Agriculture, Industry, Mortality, Social Stats), not all are indexed by name on the big websites. Use the population schedule as a guide (find the township or district your ancestor lived in, then see if the non-pop schedules have an entry for that same area).

If you can’t find these schedules online for your ancestor’s area, contact the National Archives or state archive. According to NARA, agriculture, industry, mortality, and social statistics schedules survive for 1870 for most states. They are part of Record Group 29 at NARA. Sometimes only fragments survive, but generally 1870 non-population schedules are fairly complete. The National Archives even lists which microfilm publication covers which state’s nonpopulation schedules (for example, there are separate microfilm series for different states or regions).

In summary, online access is typically your first and best option for 1870 census material, with the population schedule being fully indexed and the others partially indexed or browsable. Always save copies of the images (or print them) for your records, and note the source citation (the state, county, page number, etc.) for future reference.

Tips for Interpreting 1870 Census EntriesTips for Interpreting 1870 Census Entries

Once you have located your ancestor’s 1870 census entries, the next step is making sense of them. Here are some practical tips to interpret the information accurately and avoid common pitfalls:

- Deciphering Handwriting: The penmanship in 1870 varies from beautifully neat to notoriously hard-to-read. If you’re having trouble, try comparing letters in the unknown word to other entries by the same enumerator. For example, find how the enumerator wrote capital "L" or cursive "S" elsewhere on the page. Common issues include old-style cursive “Ss” that look like “Fs”, or a cursive capital “J” that looks like “I”. If a name is unclear, write it out yourself, or even speak it aloud as written to see if it resembles a known name. An enumerator’s flourishes might make “John” look like “Jno” or vice versa (Jno was actually an abbreviation for John – many names were abbreviated). Don’t hesitate to seek a second opinion – many genealogy forums or Facebook groups will help read tough handwriting if you post a snippet.

- Watch for Enumerator Abbreviations: Enumerators used many abbreviations to save space. Some typical ones: “Wm” for William, “Chas” for Charles, “Jas” for James, “Thos” for Thomas, etc. Months were abbreviated (Jan, Feb, Mar...). “Do” or a straight quotation mark " meant "ditto" – repeating the same info from the line above (common for surname or place of birth). In 1870, you might see “Mass.” for Massachusetts or “Eng” for England in birthplaces. Occupations could be abbreviated too (e.g., “Farmer” might be fully written, but “Keeps House” for housekeeper sometimes just as “KH”). If something is ambiguous, check the column heading and other entries.

- Context is Key: Always look at the neighbors on the census page. Are the families around your ancestor related or connected? In 1870, recently freed Black families often lived near one another or near former enslavers’ families. Immigrant families might cluster (e.g., a German-born family living near other German-born neighbors). This can provide hints – e.g., if you see your ancestor is foreign-born and so are the three households around them, perhaps they all immigrated around the same time or traveled together. Noting a cluster of the same birthplace can lead you to investigate chain migration from a certain region.

- Incomplete or Inaccurate Data: Recognize that census data is not 100% accurate. Ages in 1870 are notoriously imprecise – people might not know their exact age (especially former slaves or older folks) or might round off. It’s common to see an age that’s off by a few years compared to later records. Use ages as a guideline, not gospel. Similarly, birthplaces might sometimes switch between census years (an ancestor might be listed as born in Missouri in 1870 but Illinois in 1880 – perhaps due to state boundary confusion or the respondent giving different answers). Treat each piece of info as a clue that might need verification.

- Enumerator Biases/Quirks: The 1870 census was conducted by humans who had their own biases and tendencies. Some enumerators were very diligent; others perhaps rushed. You might notice an enumerator who spelled the same name differently for two households (one might say “McDonald” and another “McDonnell”). Or an enumerator who apparently guessed at ages (lots of rounded numbers). One known issue in 1870: underreporting of sensitive info – for example, the “vote denied” column (20) was often left blank even if a Black man’s vote was likely denied in reality. If something seems off (like an obviously male name marked “female”), it could be enumerator error, as illustrated by cases of gender mistakes. Always consider that the census is a secondary source – it’s information given, transcribed, and subject to error.

- Use the Mortality Schedule Together: If you find a household in 1870 and know (or suspect) someone in the family died around that time, check if they appear on the mortality schedule. For instance, if a child from 1860 is missing in 1870 and was about 15, look at the 1870 mortality list for that county for teenagers. You might confirm a death and cause. Conversely, if you find an ancestor in the mortality schedule, go to the population schedule to see if their family is listed (the family might still be enumerated, minus the deceased). This cross-reference can confirm you have the right family and reveal how the family adjusted (perhaps an older child had to take up work after the father died, etc., which you might infer from the occupation entries).

- Corroborate with Other Records: The census provides leads that you should follow up. For example:

- If the census says an ancestor was born in Ireland and is 30 years old, you might next seek immigration or naturalization records, or church records for immigrants. The census has pointed you to an origin.

- If the census indicates your ancestor had $800 in real estate, check land deeds or property tax records around that time – you might find when they bought or sold land.

- If the census lists a specific occupation, look for records related to that trade. City directories often list occupations, which can confirm the person and sometimes give a work address. If he was a Civil War veteran (possible if he’s a male in his 20s-40s in 1870), military pension records could be incredibly rich sources to verify identity and family data.

- If the census indicates a child attended school, maybe there are school records or year-end reports in town archives that could mention student names. Or if it shows someone couldn’t read or write, and by 1880 they could, perhaps they learned in between – a minor point, but it humanizes the timeline.

- Track the Whole Family: Don’t just extract your direct ancestor – note everyone in the household and their details. Often, genealogical clues come from siblings or other co-residents. A widowed mother living with a married daughter’s family might be the key to discovering the mother’s maiden name or earlier history, for example. Also notice if any elderly persons or others with different surnames are in the home; they could be in-laws or extended kin. In 1870 especially, newly freed families sometimes had unrelated individuals (like freedmen taking in orphaned children or neighbors boarding together). Those could turn into leads on community and possible family connections in the slavery period.

- Keep an Eye Out for Second Enumerations: As mentioned earlier, a few places had second counts in 1870 due to concerns about accuracy. If your ancestors lived in New York City, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, or certain counties in Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, etc. that were recounted, you might find two entries for the same family. Usually the second enumeration is considered more accurate. The National Archives notes, for example, New York City and Philadelphia have both the June and later 1870 enumerations preserved. If you come across duplicate listings, study both – one might have small differences (like corrected ages or spelling). Be sure to record both or choose the final version for your records, but note the existence of the earlier one. It’s a quirky scenario unique to 1870 and a few areas.

In short, interpret the census data with a combination of skepticism and creativity. It’s a starting point, not the final word. Use it to generate hypotheses: if something looks a little off, ask yourself why and seek another record to confirm or clarify it. For every entry on the census, consider what other record types might enrich that data – vital records, church registers, land and probate files, newspapers, city directories, military records, etc. The 1870 census is one piece of the puzzle, but when combined with other sources, it can help solve mysteries about your ancestors’ lives.

New Racial Categories in 1870 and Their Impact on ResearchNew Racial Categories in 1870 and Their Impact on Research

The 1870 census was notable for how it recorded race. It was the first U.S. census to include specific categories for “Chinese” and “Indian” in addition to White, Black, and Mulatto. This change reflected demographic shifts – notably, increased Chinese immigration during the 1860s, and the presence (albeit limited in the census) of Native Americans in certain areas. Understanding these categories and how they were used will help if you are researching ancestors of African American, Native American, or Asian (particularly Chinese) heritage.

- African American Ancestors: In 1870, African Americans were primarily recorded as either Black (B) or Mulatto (M) in the race column. Enumerators made this distinction often based on appearance or local knowledge. “Black” generally denoted fully or predominantly African ancestry, while “Mulatto” was used for persons of mixed race (part African, part European, for example). In practice, the usage could be inconsistent; one census taker might label an entire family Black, while another in 1880 might label some members Mulatto (or vice versa). When you see “M,” it is a clue that the person was perceived as of mixed ancestry, which might guide you in investigating things like possible white parentage (often a plantation owner father, in slavery times) or simply note a lighter complexion line in the family. For genealogists, 1870 is profoundly important for African Americans because, as noted, it’s the first census that listed them by name. If you have formerly enslaved ancestors, finding them in 1870 can be both exciting and challenging. Keep in mind possible surname changes around that time – some freedpeople took new surnames, and some families adopted the surname of a former owner en masse. It’s also possible an ancestor might appear with one surname in 1870 and a different one by 1880 (for example, using a plantation name vs. a chosen surname). Be vigilant for alternative name spellings or aliases in records from the late 1860s and 1870s (marriage records, labor contracts, etc.). The new voting rights questions (columns 19-20) in 1870 mainly targeted African American men – if you see a mark that an ancestor’s vote was “denied or abridged,” it is a direct nod to the realities of Reconstruction: either the state hadn’t fully granted rights yet or the individual had some disenfranchising circumstance. This can prompt you to learn more about the local history of African American voting rights and perhaps find records of voter registrations (1867 voter registration lists in former Confederate states, for instance, are great resources that might list Black voters by name). Also, note that Native Black/White distinctions appear in the social statistics schedule regarding pauperism and crime – “native black” meaning Black people born in the U.S. These aggregated figures might indirectly reflect the conditions of African Americans in a community (e.g., if the social stats report a large number of “native black paupers” in a county, that signals the severe economic hardship many freed people faced).

- Native American Ancestors: The census category “Indian (I)” in 1870 was meant to denote American Indians. However, most Native Americans were not captured in the 1870 census. The federal census at that time generally excluded “Indians not taxed,” meaning Native Americans who lived on reservations or in nomadic communities that did not interact with the formal economy were not enumerated. Some Native Americans who lived in mainstream settlements or outside of reservations were counted, and they would be marked as Indian (I) in the race column. Additionally, certain areas like Indian Territory (what is now Oklahoma) had no census taken in 1870, because those were sovereign tribal lands at the time. So if your ancestor was a Native American living in Indian Territory, you will not find them in the 1870 federal census at all – you’d need to use tribal records or later “Indian Census Rolls” (which start in 1885 for some tribes). If your Native American ancestor lived in a state (say, an Oklahoma Cherokee living in Kansas, or a Wampanoag in Massachusetts), they might appear as Indian in 1870. When you do see “Indian” as the race, check the context: occasionally, enumerators might list a person as Indian who was of mixed ancestry or in a multi-racial household. Also, the presence of “Indian” category was new, but the full counting of Native Americans was not done until 1890 (and even then, “Indians not taxed” were in a special separate count. So expect Native entries in 1870 to be relatively rare and possibly limited to certain regions (e.g., there were some in upstate New York, New Mexico Territory, Michigan, etc., where Native individuals or families lived integrated with others). For genealogists researching Native roots, if you believe your ancestor was Native American but you don’t find them in 1870, that doesn’t mean they weren’t there – they just might not have been counted. Cross-reference with Bureau of Indian Affairs records or later censuses. If you do find a Native American listed, use that as a springboard: try to determine tribal affiliation from other sources (the census won’t state tribe). Perhaps local histories or the 1900 census (which did have a “Indian tribe” field) can help if the person lived that long.

- Chinese and Asian American Ancestors: The inclusion of a “Chinese (C)” category in 1870 was a response to the growing population of Chinese immigrants, especially in California and the Western states. Chinese immigrants (primarily men in this era, who came to work on railroads, mining, etc.) were enumerated in 1870 often in group quarters like mining camps or railroad camps, as well as in Chinatowns in cities like San Francisco. If you have early Chinese-American ancestors, the 1870 census is likely the first U.S. record where they would appear. They will usually be marked “C” in the race column. Note that “Chinese” in 1870 could include anyone East Asian in practice – at that time, Japanese immigration was extremely limited (and the census did not have a separate category for Japanese until later), so any Japanese or other Asian individuals could have been misclassified as Chinese by an enumerator unfamiliar with distinctions. (The 1880 census also used the same categories as 1870.) When researching Chinese ancestors in 1870, be prepared for very unusual name renderings. Many Chinese names were Anglicized phonetically by enumerators who had trouble with them. You might see names like “Ah Wong” or “Lee Sing” which may only be part of a traditional Chinese name. Sometimes the surname might be first or second – it can be tricky. If you suspect an ancestor should be there but you can’t find them by name, try browsing the area manually. For example, many Chinese were in mining regions of Idaho, Montana, Nevada, etc., so the census pages might list dozens of Chinese laborers. The genealogy search indexes might not handle the names well, so manual review can be necessary. Also consider that return migration was common: many Chinese workers eventually went back to China. So you might find them in 1870, but they could be gone by 1880. If you find a potential ancestor in 1870, you can then check sources like Chinese Six Companies records, if available, or later immigration records (though the major wave of Chinese Exclusion Act paperwork comes post-1882). For other Asian American groups: very few appear in 1870. A small number of Japanese individuals were recorded (often students or samurai visitors in places like California – they might have been recorded as “C” or sometimes written as Japanese). Asian Indians (from India) were extremely rare in 1870; the term “Hindoo” appears in later censuses (like 1900) but not in 1870. If you have early Filipino or other Asian ancestry in Louisiana or elsewhere (like the historic Filipino community in Louisiana’s St. Bernard Parish), they might have been recorded under various designations (some Filipinos were recorded as “Mulatto” or “Black” in earlier times). By 1870, those communities might appear as just regular citizens without a special race category, depending on how the local society viewed them. Researching those ancestors might involve looking beyond just the race column, since the census might not fully capture their identity.

Implications for Research: The racial categories in 1870 can sometimes be a clue and sometimes a complication. For African Americans, seeing “B” vs “M” might lead you to investigate possible mixed heritage or to be aware of potential changes in how family members were identified in records. For Native Americans, you learn that the lack of an ancestor in the census doesn’t necessarily mean they weren’t around – other records must fill the gap. For Chinese/Asian ancestors, you gain an early foothold in records, but you might have to deal with non-standard names and should be aware of later events (like the 1880–1900 era of exclusion) that affected record-keeping.

Also, recognize that enumerator error or personal identity could lead to some surprises: occasionally, mixed-race individuals could be listed with an unexpected category. An individual of mixed African and Native descent might be just listed as Black, or someone of mixed white and Native might just be listed as White (if they were assimilated). The census-taker made the call. So use other clues (names, neighbors, etc.) to supplement what the race column says.

In summary, the 1870 census’ approach to race was a product of its time – it codified people into five labels. While those labels are outdated and overly simplistic, for genealogists they are important data points. They can validate family stories (“Great-great-grandpa was Chinese – yes, here he is marked C in 1870”) or open new avenues (“Why is this ancestor marked Mulatto? Could her father have been someone not of African descent?”). Always consider the historical context: 1870 was just the beginning of a long journey in how the census tracked race and ethnicity, but for the people recorded, it was a reflection of how they were viewed in that era.

State and Regional Variations in 1870 Census RecordsState and Regional Variations in 1870 Census Records

When using the 1870 census, it’s helpful to know about some state and regional quirks that might affect your research. Not all parts of the 1870 census are equal in quality or completeness. Here are key variations to be aware of:

- Missing or Lost Schedules: Fortunately, the 1870 census did not suffer a catastrophe like the 1890 census fire, but there are a few losses. As mentioned, Minnesota’s federal copies for many counties (Aitkin through Sibley alphabetically) were destroyed. Thankfully, Minnesota had state copies of those schedules, so none of the information was truly lost – it’s just that you have to rely on the state copy (microfilm T132) for those counties. Researchers using Ancestry or FamilySearch likely won’t even notice, since those sites have merged both federal and state copies for Minnesota. But if you’re hunting on microfilm or in older index books and see notes about missing counties, know that Minnesota’s census is intact via the state version. Always check if the area you need might have a state copy. Some territories also filed copies – for example, Dakota Territory might have duplicates in state archives of North/South Dakota. A quick visit to the National Archives FAQ or state archive website can clarify if any portion is missing. In general, aside from Minnesota, the 1870 population schedules survive for all states and territories that were enumerated (Indian Territory being a case of “no census taken” rather than missing).

- Second Enumerations/Recounts: Certain urban or fast-growing areas had their census done twice. For example, New York City (New York County) was first counted in summer 1870, but then a second enumeration took place in January 1871. Philadelphia had a recount in November 1870. Indianapolis, Indiana had a city recount in early 1871 that was accepted as official. Some smaller places: Junction City, Kansas (Davis County) was recounted in Dec 1870; parts of St. Joseph, Missouri were recounted in Jan 1871; an Ohio county (Geauga) and part of another (Ottawa County townships) had recounts in March 1871. The reasons ranged from suspected undercounts to local complaints about accuracy. For genealogists, this means if you have ancestors in those areas, you might find two records for the same family. Typically, one will be labeled “1st Enumeration” and the other “2nd Enumeration” in the archives. Both are valuable: the first might have info that changed by the second (maybe a family moved in/out, or they gave different ages). It also means if you can’t find someone in a city like NYC or Philly in what appears to be the census, check if there’s a second set – perhaps the person was missed in the first but caught in the second. Modern indexes usually include both, but it’s something to keep in mind if something doesn’t line up.

- Enumeration Dates and Accuracy: The census officially started June 1, but enumerators in 1870 had a lot on their plate, especially in the Reconstruction South and booming West. In some southern states, the process was slow or met resistance. You might notice some census pages dated as late as October 1870 or even early 1871. Late enumeration increases the chance of mistakes (people moving, forgetting who was there on June 1, etc.). Also, the farther from the official date, the more likely births and deaths in between could complicate things (an infant born in July should not be listed, but an enumerator visiting in December might accidentally list them as a member of the household even though they technically weren’t born by the official date). Always check the date noted by the enumerator at the top of the page – it gives context. For example, a family member who died in July 1870 should still be listed as alive (because as of June 1 they were). If the census taker came in September, the family might mention the person died, but by instructions, they still record them. Most followed the rule, but if someone is conspicuously marked out or a note made, that could be why.

- Regional Legibility Issues: Microfilming quality can vary. Some Southern states’ records might have faded ink or bleed-through, possibly because of the paper and ink available in the post-war economy. If an image is hard to read, try alternate sources: FamilySearch and Ancestry sometimes have slightly different scans. Or, consult published transcriptions carefully. In a few cases, pages might be in fragile condition. If you encounter a really illegible page that you suspect has your family, consider contacting the archive to see if a better image is available or if the original can be consulted (many originals are very delicate, but occasionally a better microfilm or scan can be found).

- Non-Population Schedules Survival: While population schedules are almost complete, non-population schedules have some gaps. For instance, not every state’s 1870 manufacturing schedules survived; some might have been purged later or not transferred to the archives. According to the National Archives, all states have 1870 ag, industry, mortality, and social stats except a few missing bits here and there. However, the survival is uneven. For example, New Jersey’s 1870 agricultural schedule might not have made it, or a county or two could be missing. It’s worth checking NARA’s list (often in a document called "Nonpopulation Census Schedules by State"). If you can’t find a non-pop schedule for a particular state on any site, it might be that it didn’t survive or was never microfilmed. As a workaround, sometimes state-level agricultural societies published summaries of ag data, or state censuses (if the state conducted its own around that time, e.g. Kansas 1865 or 1875 state census may include similar info).

- Territories vs States: In 1870, areas like Dakota Territory, New Mexico Territory, Washington Territory, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, etc. were enumerated. They might have smaller populations with issues like scattered settlements. One notable absence: Indian Territory (future Oklahoma) had no count as mentioned. Alaska had been purchased in 1867 but was not included in the 1870 census (its first census as part of the US was 1880). So if you have people in Alaska or Indian Territory, you won’t find them in 1870. If you have ancestors in other territories, the census did cover them – just be prepared for possibly less detailed indexing (territories often had fewer people and sometimes are lumped at the end of state lists on websites).

- State Census Records: Some states took their own censuses around 1870 which can serve as supplements or substitutes if needed. For example, Kansas had a state census in 1875, Iowa in 1875, Minnesota in 1875, Illinois did one in 1865 (prior) and none in 1875, etc. While not the 1870 federal census, these can help fill gaps or verify data, especially if the federal 1870 is sketchy for some reason in that area.

- Local Issues: Occasionally, local problems like an inattentive marshal or community mistrust could lead to undercounting. There were anecdotes of freed slaves initially fearing the census (some thought it might be related to taxes or even a return to slavery), so a few communities might have undercounted African Americans in early summer 1870 until efforts were made to reassure and do supplemental counts. The fact that multiple recounts happened in major cities suggests political stakes (representation, etc.) were tied to the count being accurate. If your ancestor is oddly missing in 1870 but appears in 1860 and 1880 in the same place, consider whether they might have been missed by accident. You might look for them in 1870 under a very mangled name or in a nearby county (maybe they were temporarily elsewhere). Don’t assume they died or left the area without doing a thorough search, as enumeration errors did happen.

In summary, know your location: Each state (and even county) can have its own story for the 1870 census. A little background research on how the census was conducted in that area can go a long way. The National Archives’ resources and genealogical journals sometimes have “census snapshots” for given communities. But most importantly, if you hit a snag (missing data, weird duplications), remember it might not be your fault – it could be a historical quirk. By being aware of these variations, you can adjust your strategy (like checking state archives for a missing county, or searching second enumeration records) and ensure you don’t overlook your ancestors.

ConclusionConclusion

The 1870 U.S. Federal Census is a cornerstone for genealogical research in the 19th century. It captures a nation in transition – families rebuilding after the Civil War, formerly enslaved people establishing their identities, immigrants carving out new lives, and communities growing and changing. By exploring not just the population schedule but also the agricultural, industrial, mortality, and social statistics schedules, you can gain an incredibly detailed view of your ancestors’ world in 1870. Remember to use the data wisely: verify against other sources when you can, and use the clues to open new research avenues.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the 1870 United States CensusExplore more about the 1870 United States Census

- 1870 Enumeration Form - IPUMS USA https://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/form1870.shtml

- 1870 Census Records - National Archives and Records Administration https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1870

- 1870 Census Instructions to Assistant Marshals - National Archives and Records Administration https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires/1870/1870-instructions.html

- 1870 U.S. Federal Census - Cyndi's List https://cyndislist.com/us/census/1870/

References