U.S. ports of entry are places where immigrants could officially enter the United States, whether on a ship or over a land border with Canada or Mexico. At least 70 ports of entry served millions of immigrants throughout U.S. history. During the biggest wave of immigration in the late 1800s and early 1900s, more than half of U.S. states had at least one port.

(Note that this article focuses on voluntary immigration to the United States. For information on the forced immigration of enslaved Africans, see TransAtlantic Slave Trade.)

You can see all ports of immigration for which records exist on the National Archives website, which has a state-by-state list of ports with links to information on digitized records.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

The busiest American portsThe busiest American ports

The largest U.S. ports of immigration were New York, Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Charleston, New Orleans, Galveston, and San Francisco.[1]

New YorkNew York

About 12 million immigrants arrived in New York City. Until July 1855, passengers and crew received health inspections onboard and would be quarantined if needed on Staten Island.

Starting in 1855, immigrants were processed at Castle Garden, a fort on lower Manhattan.

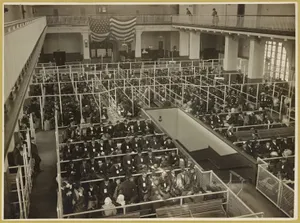

Processing moved to a a barge office from April 1890 through December 1891. The Ellis Island Immigration Station opened in New York Harbor January 1, 1892.[2]

After a fire in June 1897, processing moved back to the barge office until Ellis Island reopened with new, fireproof buildings in December 1900. The station saw its busiest day on April 17, 1907, when 11,747 passengers arrived. [3]

After the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which limited immigration, traffic through Ellis Island slowed drastically. The buildings were used as a Coast Guard station and detention center before they closed in 1954.

BostonBoston

BaltimoreBaltimore

Close to 2 million immigrants entered America at Baltimore, at the north end of the Chesapeake Bay. From the 1870s to 1920s, more than a million immigrants passed through the city’s immigration center at Locust Point, due in part to an arrangement that allowed them to depart their ships and immediately board a B&O train going west.[5]

Philadelphia Philadelphia

Philadelphia, located on the Delaware River just north of Delaware Bay, welcomed 1.3 million immigrants at its port. The Washington Avenue Immigration Station processed arrivals between 1873 and 1915. Thereafter, immigrants received health inspections at locations along the Delaware River before disembarking in Philadelphia.[6]

CharlestonCharleston

Positioned on a peninsula between the mouths of two rivers, Charleston, SC, was a busy Southern port for trade (including 40 percent of the enslaved Africans brought to America).[7] Jewish immigrants began arriving in Charleston as early as the 1690s, and for a time it was home to the largest Jewish community in the United States.[8] Other groups to immigrate here included Germans from the Palatinate, French, Scots-Irish, Scottish, and Irish.[9] Many were drawn by land offered as an incentive under the Bounty Acts of the 1700s.[10]

New OrleansNew Orleans

Situated between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, New Orleans welcomed the second-largest number of international arrivals (after New York City) during the 30 years before the Civil War. Immigrant groups included refugees from the Haitian Revolution, Irish, Germans, Central European Jews, Cubans, Italians (especially from Sicily), Eastern European Jews, and French-speaking Christian Lebanese.[11]

GalvestonGalveston

Galveston, Texas, located on Galveston Island in the Gulf of Mexico just off Houston, started with a trading post and customs house in 1825. Beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, Swedish and Norwegian immigrants began arriving via Galveston, with more Europeans following in the 1840s and 1850s due to revolutions in Europe. Between 1906 and 1914, nearly 50,000 immigrants landed here, including Eastern Europeans, Swiss, English, Italians, Dutch, and an estimated 10,000 Jews. By 1915, Galveston had a reputation as a "second Ellis Island."[12]

The city is known for the devastating 1900 hurricane, which killed thousands and caused extensive damage.[13]

San FranciscoSan Francisco

Immigrants to San Francisco included many Chinese, Japanese, Germans, Italians, Indians, Russia, Canadians, Filipinos, Mexicans, and Polish.[14]

From 1910 to 1940, Angel Island in San Francisco Bay was home to the Pacific Coast’s largest immigration station. Arrivals totaled 550,469, including 341,363 noncitizens and 209,106 US residents.

The station was an inspection point for arrivals whose paperwork needed investigation, or if they were from a country or class excluded by US law. At the time, the Chinese Exclusion Acts banned Chinese laborers from entry and heavily regulated other Chinese. Chinese immigrants made one-third of all detainees at Angel Island.[15]

Land ports in the United StatesLand ports in the United States

Immigrants who arrived in Canada and traveled by land to the United States could cross anywhere. Detroit, Michigan, and Buffalo, NY, were common crossing points. After 1894, U.S.-bound immigrants to Canada were inspected at their Canadian port of arrival.[16]

Similarly, crossings at the Mexico border weren’t monitored until about 1906. The most common arrival port for immigrants through Mexico was El Paso, Texas.[17]

Search Immigration & Travel Records at MyHeritageSearch Immigration & Travel Records at MyHeritage

See alsoSee also

Explore more about U.S. ports of entry for immigrationExplore more about U.S. ports of entry for immigration

References

- ↑ Alison Ensign, Find the U.S. Immigration Ports Your Ancestors Used, FamilySearch Blog, 22 July, 2023,https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/find-the-u-s-immigration-ports-your-ancestors-used

- ↑ Overview and HIstory, Ellis Island, The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., https://www.statueofliberty.org/ellis-island/overview-history

- ↑ Remembering Ellis Island’s Busiest Day: How Has Immigration Changed Since 1907?, April 2019, The Immigrant Learning Center, https://www.immigrationresearch.org/node/2858

- ↑ Researching Your Family's History at the Massachusetts Archives: Passenger Lists, Massachusetts Archives, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/divisions/archives/research/family-history.htm

- ↑ A City of Immigrants, Baltimore National Heritage Area, https://www.explorebaltimore.org/city-history/a-city-of-immigrants

- ↑ Entering America: The Washington Avenue Immigration Station, The Philly History Blog: Discoveries From the City Archives, 21 January 2009, https://blog.phillyhistory.org/index.php/2009/01/entering-america-the-washington-avenue-immigration-station/

- ↑ Establishing Slavery in the Lowcountry, African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations,https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/africanpassageslowcountryadapt/sectionii_introduction

- ↑ Charleston Jewry: 320 Years and Counting, Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina,https://jhssc.org/charleston-history-2/

- ↑ Nic Butler, PhD, German Palatines in Colonial Charleston, Charleston County Public Library, 27 April 2017,https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/german-palatines-colonial-charleston

- ↑ South Carolina: The Bounty Act of South Carolina, BoydRoots.Net, https://boydroots.net/Places/southcarolina.html#:~:text=The%20Bounty%20Act%20of%20South,land%20if%20they%20settled%20it

- ↑ Emily Perkins, Coming to New Orleans: A new series on the city’s diverse immigration history, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 18 May 2023, https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/coming-new-orleans-new-series-city%E2%80%99s-diverse-immigration-history

- ↑ History of the Port of Galveston, https://www.portofgalveston.com/DocumentCenter/View/26/Port-of-Galveston-Timeline

- ↑ Diana J. Kleiner, Galveston County, Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/galveston-county

- ↑ California Emigration and Immigration, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/California_Emigration_and_Immigration

- ↑ Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, Journey to America, History of Angel Island Immigration Station, https://www.aiisf.org/history

- ↑ Marian L. Smith, By Way of Canada, U.S. Records of Immigration Across the U.S.-Canadian Border, 1895–1954 (St. Albans Lists), Prologue Magazine, National Archives and Records Administration, reviewed 28 October 2022,https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2000/fall/us-canada-immigration-records-1.html

- ↑ Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History, Mexican, A Growing Community, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/mexican/a-growing-community/